EU change a blockbuster challenge for Cameron

- Published

To watch David Cameron in action is as thrilling and as empty an experience as watching a Hollywood blockbuster.

It seems impossible that he can survive the forces ranged against him, but he buys time, survives for a precious minute, which gives him an hour, which gives him a day.

But there is a hollowness too, for it dawns on the viewer that this is all about survival, buying time until it is time to fight the next battle, but there is no plan, no plot, no narrative - which makes what happens after the election, if he wins, fascinating and troubling.

The prime minister's much heralded European speech - in reality an immigration speech, external - will probably fend off the critics until he wins or loses in May.

There was one critical decision and two surprises in the speech. All three tell us a huge amount about Mr Cameron's character, style of government and prospects.

One surprise came right out of the blue, at least as far as I was concerned.

Mr Cameron said that what he did want - a restriction on benefits - would need a treaty change, external.

Even to many people well versed in British politics "treaty change" makes ditchwater look alluring by comparison.

But the very phrase sends a frisson through those of us sad enough to get excited about European politics.

This is because the letter at the beginning of "treaty" stands for "trouble" with a capital "T".

Huge challenge

Mr Cameron has made a solemn promise, external to hold a referendum on the UK membership of the EU in 2017.

If it really needs treaty change, it is hard to see how he can keep this politically vital vow.

Imagine a juicy ripe fruit, ready for the picking, that might even spoil if not plucked soon.

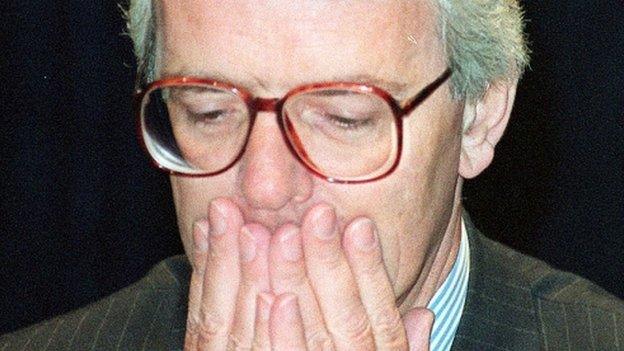

John Major signed the Maastricht Treaty in the face of much internal opposition from his own party

Then imagine that the prize lies within a thicket of thorns. To get it, you have to reach past the prickles.

Some of these spikes are poisonous - there's a chance that one scratch could prove fatal.

Then realise you have to steel not only yourself to reach out into the toxic tangle but that you have to persuade 27 other people to risk (political) death as well. That is the challenge of treaty change.

A part of me suspects Mr Cameron has overstated the case and that these changes may not require this drastic step. But not many agree with that view.

The most comprehensive academic analysis, external I have seen of the speech, by Prof Steve Peers, states clearly: "Most of Cameron's specific proposals will require a treaty amendment," although he does open the possibility it could be fast-tracked.

Viviane Reding, until recently vice-president of the European Commission and now a senior Member of the European Parliament, told me that Mr Cameron's plan was "an absolute contradiction with the treaties and with the laws that have been developed out of them".

"It would be challenged at once in the European Court of Justice, and the court applies the treaties."

Lessons from history

Treaty change is difficult because it needs the agreement of all member countries, it is toxic because of history.

Just look at the plans, external that have been floated for an ambitious treaty setting up a common economic policy for the Eurozone.

There are many in the European Union who think that this is urgently needed.

For some, not doing it risks future financial mayhem, on top of all we have seen.

For others it is another chance, perhaps a final chance, to further their dream of "ever closer union".

But Germany, which will get what it wants in this case, has shown little real enthusiasm because the risks are so great.

The European Union should perhaps have learnt its lesson from the convulsions that attended the birth of the Maastricht Treaty, external.

But the shock of Lisbon was more profound.

The European Constitution took four years to negotiate but was rejected in referendums by the Dutch and the French, external in 2005.

It was reincarnated as the Lisbon Treaty, external, which took another three years, only to be rejected by the Irish, external in 2008.

They voted again in 2009, this time the way the powers that be wished.

The treaty took up the best part of a decade. A treaty in 2024 would not help Mr Cameron much.

So anyone bouncing to the front of the room shouting: "Who's for treaty change ?" will be heard in deafening silence.

This is not to say there will never be another treaty change. There will be. But the road to it is unpredictably long and fraught.

Optimistic scenario

Let us cast our minds into an imagined future and, at that, an optimistic one for a victorious conservative prime minister.

Germany's Angela Merkel will be focused on a general election in 2017

Against all the odds Mr Cameron, using most of the energy available in his second term, wins everything he wants, and the other EU countries agree to enshrine a restriction on benefits paid to migrants in the Treaty of Rochester.

But the people of, let us say, Lithuania, angry with their government over largely unconnected economic woes, reject it in their own referendum.

Oops. Mr Cameron has, despite winning, lost, and has nothing to put to people in a referendum - delaying the promised vote would be almost inevitable, until the mess was sorted out.

Of course it may go more smoothly than that. All EU countries will do their best to avoid putting any plans to the people.

They may succeed. But this will create more friction in a fractious union, especially if the Brits are being given special rights. And it will still take time.

Mr Cameron's demands, while not unachievable, are a tough sell.

They are intended after all to remove one of the benefits of joining the EU for Eastern countries and, indeed, the citizens of any countries in a worse position than the UK, which certainly takes in France, Italy, Spain and Portugal as well.

Viviane Reding told me: "It would be an extraordinarily difficult thing to get.

"It would mean 27 nations eliminating a fundamental right of their citizens, that seems to me extraordinary and improbable. I have not heard any government, apart from Mr Cameron's asking for such a change."

So this is a big deal, something even this Downing Street can't expect to map out on the back of an envelope the night before talks begin.

Unwanted distraction

Add to this the fact that the two most important countries in Europe , Germany, external and France, external, have general elections in 2017.

They hardly want the distraction of a big treaty change that year or the one before.

Especially if the main point is to grudgingly give Mr Cameron what he wants.

That suggests to hold a referendum in 2017, Mr Cameron has to get it all done and dusted some time after May next year.

All this is dawning on those in Mr Cameron's party who would rather just leave the European Union.

In one way they will be delighted if all roads lead to a referendum that would be held too early to allow Mr Cameron to proffer the spoils of victory.

But they will also know in reality that will mean the timetable will slip.

If Mr Cameron walks into Number 10 again, the very next day their battle for a referendum will start afresh.

The slow burn of treaty change comes on top of the other challenges to the Tory right contained in Mr Cameron's speech.

Curbs on free movement

He retreated from what would have amounted to a suicide attack on other European leaders and abandoned the idea of direct curbs on the number of people coming to the UK from other parts of the EU.

This is a gear-screeching U-turn, which attracts private scorn but not open rebellion from the most Eurosceptic in his own party.

The idea of taking on free movement of people was, I am told, floated by Mr Cameron himself to backbenchers.

Fuelled by a promise in his conference speech to take back control of Britain's borders, it was fleshed out in newspaper leaks and John Major's Berlin speech.

Some have suggested Mr Cameron is a study in "government by essay crisis" - like a student who suddenly realises work is urgently overdue, and scrabbles to put something brilliant together at the last moment.

In this case, he must have had a more sickening experience than this insouciance - perhaps waking in a cold sweat at 04:00 realising everything he had worked on was nonsense and would have to be ripped up.

He could have saved himself a lot of bother if he'd read this blog, or indeed listened a little earlier to what ambassadors and the Foreign Office must have been telling him.

It is widely suspected the chancellor, who does appear to think strategically as well as tactically, got him to chuck the idea in the bin.

He has got away with it.

Crisis deferred

Eurosceptics are certainly muttering - one privately told a colleague of mine that the speech would deliver a couple of million votes for UKIP.

Has Mr Cameron handed UKIP an electoral boost?

If he had said that on the record and others had joined him, it would have been a crisis for Mr Cameron.

Instead it is a crisis deferred. Many Tory Eurosceptics believe that Mr Cameron cannot and will not get the changes he wants and they will be in a good place, if they win the general election, to campaign for a "No" vote in a 2017 referendum on the UK membership of the EU.

And the other surprise?

Mr Cameron heaped praised on both the idea of the European Union and the principle of free movement.

This has been noted by the commission in Brussels with satisfaction, as the first time he has treated it with anything but hostility in a good long while.

It is being seen as an overture, a signal that he is willing to engage seriously with the commission and others.

After flirting with the idea of shadowing UKIP Mr Cameron has gone in the opposite direction.

He has defended the UK's place in the EU and announced his appetite for difficult, but achievable, changes.

If he loses the election then he's out of a job and doesn't have to worry about any of this. If he wins, the fun starts.

At the very least a newly victorious Conservative party would again be scratching away in fractious debate, and the prime minister would again be fighting on two fronts, against the bulk of other European leaders and against his own backbenchers.

At the worst, there would be civil war in the party. Three tribes would go to war, according to one interesting article - "the in crowd, the out crowd and the reform crowd".

Mr Cameron is a lithe tactician and can be expected to dodge and weave his way around the problems as they are hurled at him.

But flexibility is not always a politician's friend.

Designing and shedding policies on the lam might suggest that principles too are like an overcoat, to be abandoned when the weather brightens.

Unless Mr Cameron develops something that looks like a strategy, he will keep getting into these scrapes.