The young people going hungry in the UK this winter

- Published

The sometimes "heavy-handed" use of benefit sanctions has been partly blamed for the rise of food banks, external. But what does that mean for the young people at the sharp end?

"I'd love to be able to afford some vegetables, I really would," says 19-year-old Yasmin.

"Being a qualified cook, I'd love to make myself a nice risotto or something. But I'm not rich; I'm not posh. I can't afford nice food."

For the past year Yasmin has been living at the YMCA in Burton upon Trent.

She is one of an estimated four million people in food poverty, external - without enough money to make healthy eating choices.

'It's horrible'

The reality - particularly for poorer women - is perfectly illustrated by what she says next.

"I've gained loads of weight since I've lived in the YMCA," she says.

Sometimes she goes without. But when does eat, "it's just stuff like rice and cheap, stodgy stuff - you can't afford to eat nicely".

It's a familiar story among the hostel's young residents.

"You're so hungry," says Matt, 25. "But you're that sick of it you can't even put it to your mouth. It's horrible."

The aspiring electrician's prospects had been looking up. He was on a college course but was instructed by the job centre to take a two-week placement at Boots. By the time the placement was over, he had fallen behind and couldn't meet the college's required 97% attendance rate.

And then he had his jobseeker's allowance stopped.

Matt and the other residents of the YMCA say that going door-to-door with their CVs, or ringing around employers no longer seems to satisfy officials at the job centre.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) sanctions regime, made tougher in 2012,, external means that those out of work can have their payments withdrawn for between a week and three years if they are deemed not to have been doing enough to find a job.

Matt says that when he told the job centre about his job-searching efforts the response he got was like: "Handing your CV in, the searches you've done here - that's not applying for work. So bye-bye, see you later.

"I'm going without money at the moment - no electric, no food."

The DWP did not comment on the specifics of Matt's case but says sanctions are used only "as a last resort in a tiny minority of cases".

So far this year the average number of JSA sanctions being issued a month is 63,300 - down from more than 75,500 a month in 2013.

The department says it makes clear to jobseekers the conditions of receiving their benefits.

"If they fail to meet those conditions it's only fair that there should be consequences," a spokesman for the department told the BBC.

Nine out of 10 YMCAs are now referring those they support, like Matt, to food banks.

The charity says 79% of the referrals of young people were "as a direct result of delays in receiving benefit payments and punitive sanctions".

Mark grew up in care and says he has only lived with his mum for five years of his life

Those statistics will come as no surprise to those in the hostel in Burton.

Mark was left penniless and moved into the YMCA after he lost his job fitting Toyota car seats at the town's automotive factory.

He was sanctioned for not "actively seeking work" - although his support worker says he did everything the DWP asked of him - and is now waiting for average temperatures to drop to freezing or below for seven days, at which point he will qualify for a cold weather payment of £25 a week, external.

"When you're used to a regular weekly income from a job and that changes and you've got nothing it's hard.

"I like the working life," he says. "I don't want to be on jobseeker's."

A qualified caterer, Mark is now relying on the other struggling residents to make him meals and on food parcels from social services after maxing out on visits to the YMCA's own food bank.

Those supporting Mark at the hostel say the stress navigating the job centre system caused his hair to fall out.

The YMCA food bank in Burton is feeding more than 100 families a month

Press officer Suzi Browne says young people have told the charity's researchers they accept there have to be consequences if the rules are broken.

But Nick Clements, housing manager at the Burton facility, says it's a media myth that those struggling are "scroungers".

"It's not true," he says. "They're desperate for work."

Half an hour away, two of the day's first visitors to Coalville's New Life Church sit chatting to a volunteer.

They were sent here by the Citizens' Advice Bureau for a food parcel. But that's about all the unlikely friends have in common. Their names have been changed.

John is sharp, articulate, a budding writer and used to have a good job at a local bookies.

A volunteer at the Trussell Trust food bank in Coalville

Now he surfs from sofa to sofa and steals fresh fruit and vegetables to complement the dried, tinned and processed contents of a food parcel.

"I was 21 and thought, 'I'm an assistant manager, I'll just walk into another job'," he says. "Obviously that didn't happen."

He ended up in a nearby hostel for young, single homeless people where he met Sarah.

Before that, he admits, he "probably wouldn't have even dreamed of speaking to someone like Sarah".

But now, here they are, waiting together while church volunteers gather them three days' worth of emergency food each.

'No money for six weeks'

The UN's Prof Oliver De Schutter warned the UK against relying on food banks to feed the poor

Having left home at 17 and being separated from her baby boy when he was six months old, Sarah suffers with depression and suicidal thoughts.

She says she often goes a couple of days without a meal and last ate on Tuesday. It's now Friday.

Sarah says her benefits were stopped because she only completed five "job searches" instead of the required six - which she says is "ridiculous".

"But I don't agree with you, Sarah," John jumps in. "They say to you 'you need to apply for six jobs', you know that, and you know you're going to have no money for six weeks."

He exceeds the job centre's requirements, he says, applying for up to 20 jobs a week.

The pair leave with a tin each of beans, vegetables, meat and fish, some pasta, cereal and two tins of soup.

Coalville volunteer Richard Stroud calculates how much has been donated to the food bank

That is what the Trussell Trust says people need for three days of "nutritionally balanced, non-perishable" food.

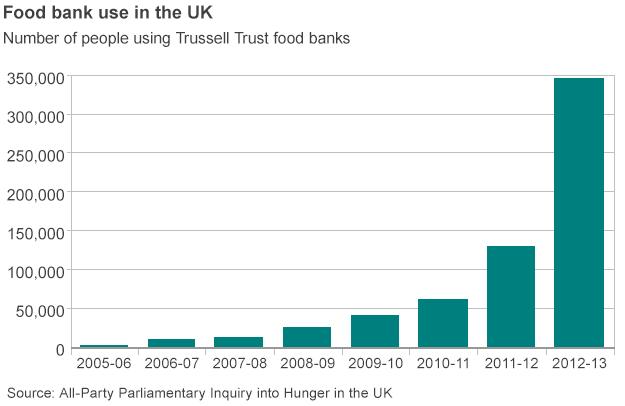

There has been a well-documented explosion in the number of people receiving these emergency rations via food banks organised by the charity.

Between 2011 and 2014, the number of people receiving Trussell Trust food parcels jumped from 128,697 to 913,138.

How does it work?

The Trussell Trust is the largest food bank provider in the UK, with over 420 facilities.

Volunteers and staff collect, catalogue and distribute non-perishable food donations from the public.

To qualify for a food parcel, recipients must have been issued with a voucher by front-line agencies such as social services, the police or doctors.

Each visitor can be referred three times before the food bank asks further questions.

Here in Coalville - a former mining town in Leicestershire with a population of fewer than 5,000 - the church is feeding more than 90 people a month, 30 of them children.

When they first opened in April 2013 it was almost a cause for celebration that their food parcels were reaching so many, says Tim Maycock, who runs the centre.

But now, as numbers grow and grow? "We often get asked the question: 'Do you think there'll be an end?' Who knows."

'Life is fragile'

A cross-party inquiry into hunger in the UK, external found that, at almost every food bank it visited, problems with benefit payments were the single biggest reason given for referrals.

And Coalville is no different, with most agencies citing delays or changes - including sanctions.

But 62-year-old volunteer Richard Stroud adds: "There are all sorts of reasons why people come to us.

"The majority of people in this country don't realise how fragile life is."

Richard Stroud was a policeman and care home owner before joining the church

Recent research by Oxfam, the Child Poverty Action Group, the Church of England and the Trussell Trust, external, found that people turned to food banks as a "last resort, when other coping strategies had failed".

One idea investigated by an all-party group of MPs was whether food banks could become "permanent features of the welfare state".

But the idea they could assume a more official, "quasi-institutionalised" role as they expand is "not acceptable", warns Prof Olivier De Schutter - until earlier this year the UN's special rapporteur on the right to food.

"Food banks should be a short-term safeguard in times of crisis," he says. "They should not become part of the system.

"The requirement that international human rights law imposes on states is to ensure that all families are sufficiently protected by either income-generating employment or by social protection in order not to have to depend on charity. It's that simple."

The DWP says the Oxfam and YMCA reports failed "to provide convincing evidence of a causal link between welfare reforms and increased use of food banks".

A spokesman adds that there is "a record number in employment in this country" and says the government spends £94bn a year on working-age benefits to provide "a strong safety net".

Hunger in the UK

4 million

people at risk of going hungry

272

food banks across big cities and towns

-

500,000 children live in families that can't afford to feed them

-

3.5 million adults cannot afford to eat properly