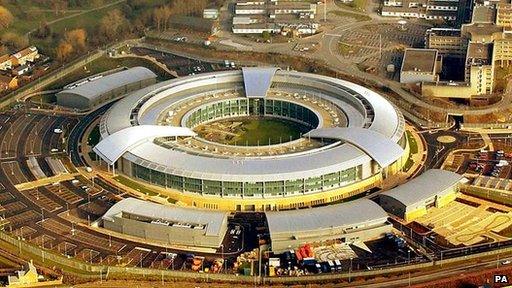

GCHQ does not breach human rights, judges rule

- Published

The current system of UK intelligence collection does not currently breach the European Convention of Human Rights, a panel of judges has ruled.

A case claiming various systems of interception by GCHQ constituted a breach had been brought by Amnesty, Privacy International and others.

It followed revelations by the former US intelligence analyst Edward Snowden about UK and US surveillance practices.

The judges said the case had been important in clarifying GCHQ's policy.

Some of the organisations who brought the case, including Amnesty UK and Privacy International, say they intend to appeal the decision to the European Court of Human Rights.

The case led to extensive disclosures of the intelligence agency procedures for handling intelligence.

'Webcam watching'

The Privacy International pressure group had said the documents released by Mr Snowden detailed the many ways that GCHQ was spying on people, many of which violated the European Convention on Human Rights.

This guarantees a right to privacy and to freedom of expression.

The group also said the programmes run by GCHQ and the United States's National Security Agency - uncovered by Mr Snowden - let the agencies listen via microphones, watch through webcams and scoop up detailed web browsing histories.

Analysis: Gordon Corera, BBC security correspondent

GCHQ will consider this ruling an emphatic victory. They will argue that it, along with other oversight reports, clears them of carrying out "mass surveillance" as their critics have claimed.

They have argued that the way they collect and then examine material is compliant with human rights obligations and the law. A central point of contention has been whether bulk access to traffic through cable taps was in itself a violation of privacy because of what it swept up. The Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) says that indiscriminate trawling for information would be unlawful but the way in which the intelligence agencies go about selecting and retaining material is proportionate and lawful.

Those who brought the case will not give up - they will go to Strasbourg and the European court and have also raised questions about the IPT process itself. But they will be disappointed by today's ruling even if it did not come as a complete surprise.

The bodies bringing the case to tribunal argued that GCHQ's methods breached article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which is the right to privacy, as well as article 10, which protects freedom of expression.

But the judges at the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) said the disclosures made during this case, which included the legal footing of the intelligence system's activities, had contributed to their decision that the intelligence agencies were not in breach of human rights.

In a written judgment, a panel of IPT judges said: "We have been able to satisfy ourselves that as of today there is no contravention of articles 8 and 10 by reference to those systems.

"We have left open for further argument the question as to whether prior hereto there has been a breach."

A government security source told the BBC: "We are delighted that a third independent body has confirmed that GCHQ does not seek to carry out mass surveillance."

'Trust us'

James Welch, legal director for civil rights organisation Liberty, said: "So a secretive court thinks that secret safeguards shown to it in secret are an adequate protection of our privacy.

"The IPT cannot grasp why so many of us are deeply troubled about GCHQ's Tempora operation - a seemingly unfettered power to rifle through our online communications."

Surveillance systems

Prism is a surveillance system launched in 2007 by the NSA

A leaked presentation, dated April 2013, stated that it allows the organisation to "receive" emails, video clips, photos, voice and video calls, social networking details, log-ins and other data held by a range of US internet firms

Tempora is the codename given to an operation to create a "buffer" to allow huge amounts of data to be temporarily stored for analysis

According to documents reported by The Guardian, the scheme is run by GCHQ and began at the end of 2011

It says the agency holds content gathered from tapped fibre-optic cables for three days and metadata for 30 days so that both it and the NSA can search and analyse it before details are lost

Amnesty UK's legal advisor Rachel Logan said the government had "managed to bluff their way out of the case" by "retreating into closed hearings and constantly playing the 'national security' card".

"We have had to painstakingly drag out every detail we could from an aggressively resistant government."

She also said the IPT's ruling was a "disappointing, if unsurprising, verdict from an overseer that was in part assessing itself".

"The government's entire defence has amounted to 'trust us' and now the tribunal has said the same," she added.

"Since we only know about the scale of such surveillance thanks to Snowden, and given that 'national security' has been recklessly bandied around, 'trust us' isn't enough."

- Published6 November 2014

- Published14 July 2014

- Published13 May 2014