In defence of young adult fiction

- Published

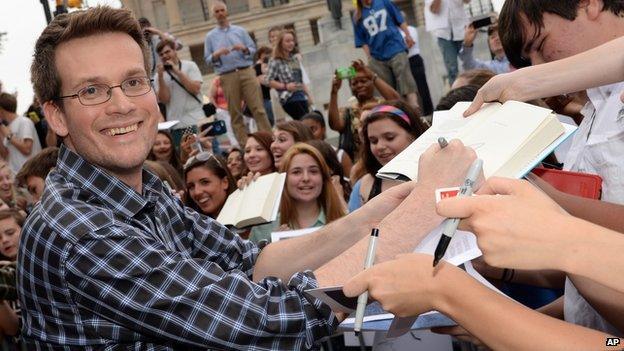

The film adaptation of John Green's Fault in Our Stars topped UK and US box office charts

Young adult fiction is selling in huge quantities and has spawned box office-topping film adaptations in Twilight, The Hunger Games and The Fault in Our Stars. Yet the genre's credibility remains largely dismissed outside its core demographic.

Inspired by a friend who died aged 16 of thyroid cancer, John Green's The Fault in Our Stars touches on a subject as emotive for adults as teenagers.

Hazel Grace Lancaster and Augustus Waters are teenagers who meet at a cancer support group and fall in love.

It has become a worldwide success, with the 2012 novel having already sold nine million copies by the time its film adaptation topped the UK and US box office charts earlier this year.

But for Samantha Shannon, author of The Bone Season series, the book still suffers from the label of "young adult fiction", or YA.

She believes the genre's wide selection of novels, from James Dashner's The Maze Runner to Stephenie Meyer's Twilight, are tarred with the same brush - dismissed as works only for teenagers.

"I do feel there is a sense of young adult fiction being looked down upon," Shannon explained to BBC Radio 4's Today programme, when invited on the show by guest editor and singer Tracey Thorn.

Caitlin Moran (l) and Samantha Shannon (r) join Today programme guest editor Tracey Thorn

She said: "There is a very strong sense of these novels [being categorised] both in terms of genre and age limit.

"But the idea that all YA is bad and doesn't challenge you in any way is ludicrous."

Shannon believes adults should not belittle the genre just because it is populated predominantly with teenage characters: "There's this bizarre idea that adults can't empathise with teenagers - even that there's something embarrassing about reading books about young people.

"That indicates to me that they're saying there's something fundamentally embarrassing about being a teenager."

Fault in Our Stars author John Green's status has been compared to that of a rock star, with 3.5 million followers on Twitter - whom he calls his "Nerdfighters"

For broadcaster and author Caitlin Moran, young adult fiction also suffers from being pigeon-holed as a genre for girls.

She said: "The majority of it is written by and read by women, and the problem with anything women do is that it's looked down on, even though it sells more.

"The phrase 'chick lit' tells you everything you need to know about the way that people feel about women who write and read books, and the way that things are categorised.

"There are no categories for male fiction, it's all just 'books'."

But she believes the importance of the genre for girls should not be underestimated.

"One of the big things that YA has done over the last couple of years is put forward very strong female role models," she explains, particularly in a landscape dominated by what she describes as the "pretty girl" and the "manic, pixie fairy girl".

But she does worry that female protagonists in the genre's biggest titles, from Veronica Roth's Divergent to Suzanne Collins's The Hunger Games, are unnervingly resolute and heroic - both physically and emotionally.

Divergent's protagonist Tris (played by Shailene Woodley) lives in a society divided into five factions based on virtues

"If I was a teenage girl and my big teenage female role models at the moment were all people in a dystopia who had to save the world, that's quite a lot of pressure when you're 13 and you're still trying to… work out what to do with your hair," says Moran.

For Shannon, however, the genre's limitations come not from the characterisation of protagonists, but from how authors are expected to conform with the most successful novels.

In particular, she feels her own work is pinned back by comparisons to the genre's most notable export - The Hunger Games's Katniss Everdeen, played on the big screen by actress Jennifer Lawrence.

The third instalment of the film franchise, which centres on Everdeen - the reluctant heroine of a brutal reality show - accounted for two out of every three cinema tickets sold in the UK during the first week of its release in November.

But Shannon believes the film's success does not excuse the fact she regularly faces questions such as 'Is your character based on Katniss Everdeen?' and 'How is she like Katniss Everdeen?' when asked about her own novels.

Katniss Everdeen, played by Jennifer Lawrence, is the face of the rebellion in a dystopian society

"YA fiction with female characters," she explains "is now judged in a slightly different way to [books] with male characters," adding that the latter would not consistently be held up against Sherlock Holmes or Harry Potter.

The success of young adult novels and their film adaptations has seemingly served only to reinforce preconceived ideas about the genre's characterisations.

But perhaps this masks a great irony.

Moran, a self-confessed "snob" in her reading preferences as a teenager, explains she purposefully read novels from the 19th and early 20th centuries as a girl, rather than those which would now be classed as young adult fiction - all in an attempt to feel more sophisticated.

"But now if I look at those books - Gone With the Wind and Jane Eyre, everything by the Bronte [sisters], all the [Jane] Austen novels - the female characters in them are teenagers," she says.

The teenage Moran was "inadvertently reading young adult fiction". And perhaps many of the adults who scorn the likes of The Fault in Our Stars and The Hunger Games are doing exactly the same.

Tracey Thorn guest edits BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Saturday 27 December, 07:00-09:00 GMT - or listen again online.

- Published24 February 2014

- Published28 November 2014

- Published19 June 2014

- Published29 November 2014