The complex case of joint enterprise

- Published

Gangs and crime: But are all guilty?

On 10 August 2007, Garry Newlove left his house in Warrington, Cheshire, to confront a group of youths he believed had vandalised his wife's car.

During the short confrontation, he was kicked to death.

Jordan Cunliffe was one of three convicted of his murder. At the time, he had severe keratoconus, a degenerative eye condition and Jordan's visual impairment meant he qualified for registration as a blind person.

Cunliffe has always denied being involved in the assault that led to Garry Newlove's death, but he was convicted under a powerful legal doctrine known as joint enterprise which allows the prosecution of members of a group or gang for murder when it cannot be proved which member of the group inflicted the fatal blow.

Joint enterprise can apply to all crimes, but in recent times, it has been used as a highly effective way of prosecuting homicide, especially in cases involving gangs of young men.

However, it is highly controversial because, many believe, it lowers the burden of proof on the prosecution and allows those who are simply too morally remote from the crime, bit-part players or not even players at all, to be swept up in a prosecution and convicted on the basis that they were all "in it together".

What makes joint enterprise so contentious is the test that lies at its heart.

In murder cases, it does not require a member of the group to intend to kill or commit serious harm. It simply requires them to foresee that another member "might" kill, or at its lowest level of culpability, "might" inflict serious harm.

If that test is passed and a person is convicted of murder, they will receive the mandatory life sentence.

Judicial concern

Jordan Cunliffe's mother has described the effect of Jordan's eye condition at the time of Garry Newlove's murder.

"He wouldn't even be able to see me, let alone if my face was angry. He would look toward the sound of your voice, not at your actual face," she says. And when outside the home, "what he relied upon was the people who were with him. Whoever was the closest to him he would hold the bottom of their sleeve, or they would hold his."

A report used at the trial concluded that he was "unable to perform any tasks for which vision is necessary".

Jordan Cunliffe has had one appeal dismissed by the Court of Appeal, but is hoping that the Criminal Cases Review Commission will refer the case back for a second appeal.

Central to that would be a new report by Dr Roger Davis, an American clinical psychologist who has developed a visual simulation technique which enables him to reproduce in photographs what a person with Jordan's visual impairment would have been able to see.

A photograph adjusted (right) to show the quality of Jordan Cunliffe's vision

Above are two photographs which compare normal vision with that of a person with Jordan Cunliffe's condition.

The difference is stark, but how might it be relevant to a joint enterprise conviction? How could what Jordan Cunliffe could see have a bearing on what he could have foreseen?

"The timeframe was very short. If you look at the images you see that Jordan is not able to see anyone's face. He's not able to tell the locations of people. He would not be able to predict what people were able to do. There's absolutely no way that he could follow the movements of other individuals. He couldn't track their movements. I doubt that he understood anything of what was going on," says Dr Davis.

Garry Newlove was attacked outside his house in Warrington in August 2007

Garry Newlove's widow Helen, now the Victims' Commissioner Baroness Newlove, did not want to address the issue of joint enterprise in the trial of those prosecuted for her husband's murder.

Her experience has made her determined to make things better for victims, and she says simply: "My husband Garry is gone and the pain and suffering of losing him in the way that we did will never go away for me or my family."

Jordan Cunliffe's case is highly unusual.

Few of those convicted under joint enterprise will have his visual impairment, but there is widespread concern about the way in which joint enterprise is used.

Duelling aristocrats

In December, the Justice Committee, external called for an urgent review into its use to prevent overcharging. Its report noted that a large proportion of those convicted were young black and mixed race men.

The government has said it will consider the report.

There has also been high level judicial concern. The former President of the Supreme Court Lord Phillips has said joint enterprise is "capable of producing injustice, undoubtedly".

Last April, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism used Freedom of Information requests to examine the use of joint enterprise.

It found that in the preceding eight years, more than 4,500 people were prosecuted for homicides involving two or more defendants. That meets the Crown Prosecution definition of joint enterprise and represents 44% of all homicides.

In the same period, 1,800 people were prosecuted for homicides involving four or more defendants, which a broader group of experts agreed must rely on joint enterprise - that's a fifth of all cases brought to court.

Joint enterprise has been around for centuries.

It was originally used to stop aristocrats from duelling, by allowing all those involved in the duel, including the doctors and seconds, to be charged with murder along with the duellists.

Perhaps most famously it was used in the 1952 trial of Derek Bentley.

Then 18, Bentley and 16-year-old Christopher Craig tried to burgle a confectionery warehouse in Croydon in south London but were caught in the act.

Derek Bentley was convicted and hanged on the joint enterprise doctrine

Craig shot dead a policeman, Sidney Miles, on the roof but Bentley was also convicted of murder and hanged.

Although Craig fired the fatal shot he couldn't be hanged due to the fact he was 16.

The words Bentley is supposed to have shouted at Craig, "Let him have it", before he fired, formed the vital evidence of joint enterprise at his trial. The prosecution used it to assert that they were in it together and had a common purpose.

Derek Bentley was posthumously pardoned.

However, joint enterprise remains a vital prosecuting tool in bringing to justice the perpetrators of some of the most heinous crimes.

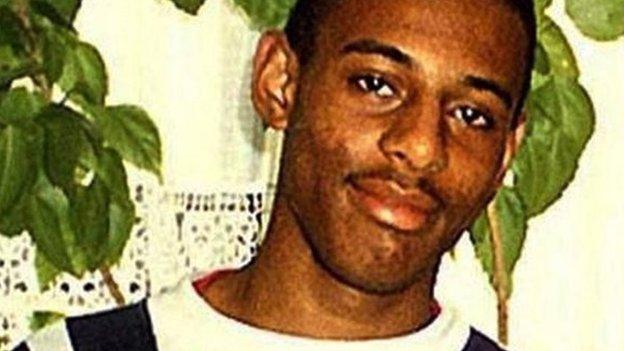

Gary Dobson (left) and David Norris were convicted of the murder of Stephen Lawrence

There was no way of knowing which of the men who attacked the black teenager Stephen Lawrence inflicted the fatal blow.

Gary Dobson and David Norris could not have been convicted of Stephen's murder, 18 years after it took place, without joint enterprise.

Many, including the police who use it in educational videos, believe that it also acts as a deterrent that will stop some young people from associating with gangs whose members might turn violent.

Prosecution guidance is clear that accidental presence at the scene of a crime or mere association with an offender is never enough to create liability - a suspect has to assist or encourage the offence in some way.

It also specifies that the prosecution should only use association evidence if, together with the other evidence, it establishes that the suspect was intentionally assisting or encouraging the offending. But concerns remain.

Campaign group Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association (Jengba), which wants to see the law reformed, works with more than 500 people who have been convicted of murder or manslaughter under joint enterprise.

Last month, three murderers won the right to appeal against their convictions after a fellow gang member confessed that he was the only one to actually stab the victim.

That evidence was not available at the trial. The case of the four men Aziz Miah, Asif Kumbay, Kirush Nanthakumar and Vabeesan Sivarajah - who has confessed to the attack - will give the Court of Appeal its first chance to consider the use of joint enterprise since the highly critical report from the Justice Committee.

Few deny that joint enterprise is an essential prosecuting tool. What is at issue is whether it is being used fairly.

- Published17 December 2014

- Published7 July 2014

- Published1 April 2014