How do we go about saving democracy?

- Published

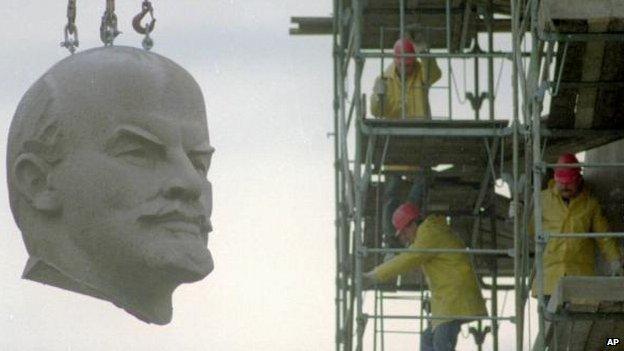

Lenin: No fan of democracy

To understand modern democracy, it is necessary first to forget about the ancient Greeks.

Pericles, Cleisthenes and all the rest of them may have made colossal strides in achieving rule by the people. But it was on terrain so unfamiliar to us today that if we go there, we are certain to get lost.

Our democracy is representative not direct, a creature of national, not city, identity, as it was then.

Its true forbear is the Westphalian settlement, external of 1648, which marked the end of the Thirty Years War, a conflict between the Catholic and Protestant states of the fragmenting Holy Roman Empire, which dominated a vast tract of central Europe.

That settlement made it possible for the first time to think of the European world as divided into separate and sovereign nation states.

Once these various bunches of people got used to thinking of themselves as bound together by various shared ties, languages and histories, then the next step naturally became one of organising their own government - not taking orders from a despot.

The representative democracy we have today emerged out of a succession of grand battles in the 19th Century between competing interests, for example workers versus those with money.

Following World War One, the idea of government by (the representatives of) the people had grown into the new common sense of Europe.

International spread

With the decolonisation of the world in the years after 1945, successive new states embraced European forms of government even as they rejected European rule.

The collapse, external of the Soviet Union precipitated another dizzy spin in the direction of democracy.

World War One marked a significant moment in the development of democracy

By 2000, only China and a few antediluvian renegades were holding out.

The 1648 settlement to sort out a religious squabble in Europe had framed the political future of nearly the whole world.

Even China - which has embraced the market - is coming under pressure to allow more political freedom.

But the problems we see in democracy today flow out of the imperfections in the way the system has evolved.

First, there is the implausibility of the idea of a homogenous national identity - that a nation state can be made up of a single group of people without leaving anyone outside.

The peace that ended World War One sought to deal with this by stressing the importance of minority rights - not those of individuals but rather of nations within nations.

Weakness exposed

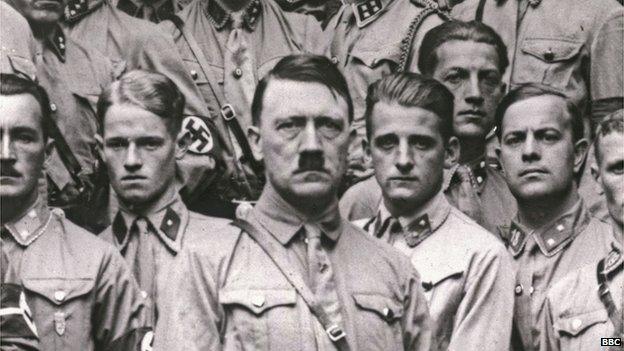

But Hitler exposed this weakness in democracy in a way that even his total defeat could not eradicate.

He showed how the general populace could be inspired by the idea that they were all one people or "Volk, external".

But he also showed how minority rights abroad could be turned into an excuse for imperial aggression - all those Danzig and Sudetenland Germans in Poland and Czechoslovakia that "needed" Hitler's protection.

Hitler exposed the weaknesses of the democratic system

In a mimic of this past, many countries today are moving sharply towards a narrowly nationalist version of European states, places where (as the former BNP leader used to call them) the "indigenous" majority are being contaminated by outsiders.

We also see Vladimir Putin moving into the Ukraine to protect his people's people, external.

That each could be described as democratic should give us pause.

Secondly, there is democracy's uncertain relationship with power.

BBC Democracy Day

Democracy Day takes place on Tuesday 20 January, across BBC radio, TV and online

A look at democracy past and present, encouraging debate on its role and future

2015 marks the 750th anniversary of the first parliament of elected representatives at Westminster

It also sees the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta - a touchstone for democracy worldwide

Go to the BBC News website's Democracy Day page, external, for analysis, backgrounders and explainers on the debate

The old socialists that drove so much of the democratisation of the 19th Century genuinely assumed that rule by the people would inevitably deliver their agenda, that once they had voters to persuade they were bound to win.

Marx (perhaps) and Lenin (for sure) were not convinced, the latter seeing in democracy just a new way of selecting the oppressor.

Not perfect

We don't have to go the whole way with Lenin to acknowledge that democracy has not effortlessly produced equality, that imbalances in power that preceded democratic change have been carried into the democratic era.

We must also acknowledge that, at best, politicians have to compromise with power to achieve change, and, at worst, that (as the Russell Brands of this world argue, external, following Lenin but without his political programme) the whole thing is so poisoned that it is best rejected altogether.

Russell Brand argues democracy should be rejected

Recent changes have exacerbated these two fundamental weaknesses of democracy.

Post-colonial states reshape themselves to offer preferential treatment to specific peoples within "the people".

Old animosities emerge in post-Soviet Europe, and African states fight elections between rival communities rather than over different ideas.

The growth of neo-liberalism after 1989 has empowered capital to flaunt its power over ever weakening democratic states.

Scope for prejudice

Meanwhile, the free movement of peoples that is one effect of globalisation creates more opportunities for Volk-like prejudice.

Another of its effects - the shift of economic power away from nation states towards supra-national (often unelected) bodies - makes dealing with the antagonisms these large-scale changes generate next to impossible for ordinary elected politicians.

Like rival emperors wearing no clothes democratic leaders scream abuse at each other to cover their nakedness.

Can representative government re-imagine itself so as to be fit for purpose in our global age?

The United Nations has surely gone the way of the League of Nations before it - how can nations divided within and among themselves pretend to speak with a singular voice?

But since it takes catastrophic war to re-engineer the international status quo, and fortunately we are not anywhere near such a terrible solution, we are left with a UN that limps along, impossible to replace, assailed on all sides.

Local democracy

Does the answer lie below rather than above the weakened nation states?

It is hard to imagine a local council or borough delivering the democracy that the centre has failed to hold - more corruption and even less power would be the likely result.

Something not as local as local or as big as the world seems called for, a democratic authority that binds not states but regions together.

This might allow all to punch above their weight while having basic guarantees of human rights (to secure against attacks on minority rights) and a strong bureaucracy (to get things done and reduce the opportunity for corruption).

In Europe something is at least seeming to be moving in this direction - an elected Europe not of states but of regions, with an overarching Court of Justice to keep the whole project on legal track.

Of course much needs to be done - the democratic frame is improving but still incomplete, the nation states still too powerful.

Europe does at times seem hidebound by national interests and incapable of strong action in any direction.

Even this tentative co-operative community has attracted vitriol in equal measure from powerful capitalists such as Rupert Murdoch and little nationalists such as UKIP.

Democrats everywhere need to fight for what we can get, not slink off into the shadows with a sense of moral supremacy made possible only by our abdication as citizens.

Where Europe leads, the world may once again follow - this time not to their own destruction but to the democratic betterment of all.

Prof Conor Gearty is director of the Institute of Public Affairs at the London School of Economics and Political Science.