'Don't give up on us,' police tell ministers

- Published

- comments

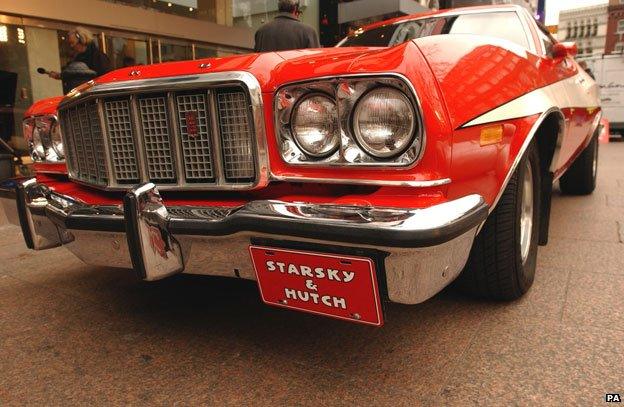

With crime now having fallen to levels not seen since David Soul (Hutch from US cop drama Starsky & Hutch) topped the charts with "Don't Give Up On Us" in 1977, police are worried the statistics will cue even deeper cuts to their budgets.

The argument goes that, if crime remains historically low, we don't need as many officers.

But today sees analysis that shows the Starsky & Hutch image of policing is far from the reality for the average officer in England and Wales.

The College of Policing has attempted to calculate a typical day in a typical force, external - and according to their analysis, there's not a lot of time for chasing bad guys in a two-door Ford Gran Torino.

Officers might expect to make 50 arrests and deal with 101 anti-social behaviour incidents every 24 hours, but an increasing amount of their effort is spent on what is called "public safety and welfare" (PSW) work.

According to the College, officers will respond to 14 incidents flagged as being linked to mental health issues on a typical day. They will probably have to detain one or two of those people under the Mental Health Act and, often, use police vehicles to transport those patients to a secure mental health facility.

The average day will also see police responding to 12 missing person reports, an increasing workload as risk-averse care homes and other agencies tend to call the constabulary sooner these days. Recent research in London suggests the Met now receive more calls for missing people than burglaries.

According to a recent report from Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), 44% of police calls are for PSW incidents, equivalent to all the calls about crime and anti-social behaviour put together.

The College's central argument, though, is not about reacting to calls from the public, but the increasing amount of resources required for on-going monitoring and support work.

The typical force on a typical day will share responsibility for 1,000 children subject to Child Protection Plans, 1,600 domestic abuse victims, 2,700 families enrolled in the troubled families programme, as well as monitoring 1,189 sexual and violent offenders in partnership with other local bodies.

This vital work almost certainly prevents significant amounts of crime, but the problem for the police is that you can't measure crimes that never happened.

The Home Secretary Theresa May, on taking up office in 2010, told police their job was to "cut crime, no more and no less", but there is a public expectation that officers will be there to deal with a lost child, the confused old gentleman, the burst water main and neighbours who should turn their music down.

These days we would also be quick to blame them if they didn't fulfil their responsibilities in monitoring those who are at risk or who might pose a risk.

As cuts to other public services bite, the police plea to ministers is that, despite big falls in crime, the government should listen to the words of David Soul: Don't Give Up On Us.