Do police believe they are above the law?

- Published

There is no person or organisation that has as much potential power over us as the police.

They can arrest us, stop us in the street and search us, fingerprint us and take our DNA.

They are allowed to retain some of our personal information on their own computer databases - and access details held by other organisations, on request.

They can monitor our movements on CCTV and trace driver records via a car number plate recognition system known as ANPR.

Details of our phone records can be obtained, and, with the home secretary's approval, phone calls and emails may be intercepted.

Sometimes, police are permitted to detain us in custody - for up to four days (seven in terrorism cases); determine the length and conditions of bail while they carry out an investigation; and in some cases, caution or charge us with a criminal offence.

In addition to all that, officers have equipment - handcuffs, batons, CS spray, Tasers, firearms - that can be deployed, when necessary, proportionate and reasonable in the circumstances to do so.

It is quite a list - and it would be surprising, despite the numerous safeguards that are in place to prevent abuse, if, on occasion, police officers didn't overstep their powers.

Lord Hanningfield won damages for unnecessary arrest

In February 2013, for example, Lord Hanningfield, who had been jailed for false accounting over parliamentary expenses, won £3,500 damages after suing Essex Police.

The former Conservative peer said he had been unlawfully arrested as part of a police investigation into the alleged fraudulent use of a county council credit card, an inquiry that was eventually dropped.

The High Court judge hearing the case, Mr Justice Eady, said he had considered whether the arrest had been necessary "to allow the prompt and effective investigation".

He ruled that it had not. "I have come to the conclusion that the requirement of 'necessity' as laid down by Parliament has not, on any realistic interpretation of the word, been met," he said.

Subtle misuse of powers

Critics of the police say that such cases happen far more frequently than we realise.

Although officers may not beat confessions out of suspects, routinely doctor their statements and fit them up, as it was alleged happened in the 1970s and 1980s, it is argued that the more subtle misuse of police powers goes on every day.

Sean O'Neill, crime editor of the Times, says his attention was drawn to it by a series of cases involving journalists.

First, came a wave of arrests of reporters suspected of hacking mobile phone voicemails, making illegal payments to public officials or misusing computer data.

A total of 148 people have been arrested as part of operations Weeting, external, Elveden, external and Tuleta, external, 63 of whom are journalists.

Many were detained during dawn raids at their homes, some with their children present.

"It was a show-of-strength issue," says Mr O'Neill, speaking in a personal capacity.

He argues that police interviews could just have easily been conducted with suspects by appointment, as they subsequently were in later cases.

Dawn raids

The tactic of early raids, often used by police, is defended by Alex Marshall, chief executive of the College of Policing, which is responsible for setting standards of professionalism and integrity.

Mr Marshall says suspects have to be detained before they leave for work, while starting early helps to maximise the time available for questioning.

"It does make sense," he says, but points out that arrests need to be "necessary".

The police use of bail, under which suspects are released from custody after questioning with conditions attached, has also come under scrutiny.

The decision to bail some of the Weeting, Elveden and Tuleta suspects for months and in some cases two years or more while inquiries continued, made Mr O'Neill "wake up" to a practice he believes is widespread.

A snapshot survey of 40 forces - compiled by the BBC last year - showed that at least 71,000 people were on police bail in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, including 5,480 who had been bailed for more than six months.

One individual, arrested by the Metropolitan Police, had been on bail for three and a half years.

Mr Marshall acknowledges that in some forces, police bail has not been well managed, with suspects arrested too early in an investigation and then bailed while numerous inquiries take place.

The College of Policing recommends that bail should not exceed 28 days unless there are "exceptional circumstances".

The Home Office is planning to legislate to put that into effect.

'Plebgate' case

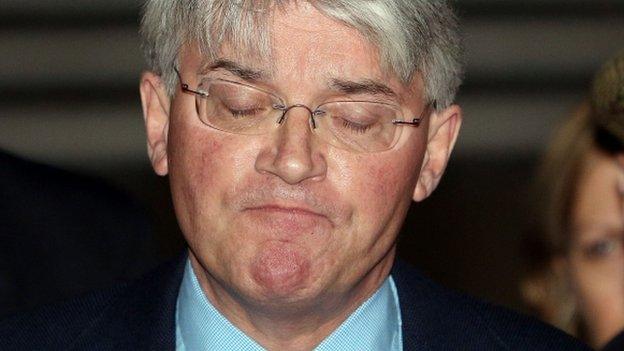

Finally, Mr O'Neill points to the so-called "plebgate" case, involving the former Government Chief Whip, Andrew Mitchell, as an example of the way in which police are misusing their powers.

Andrew Mitchell faces a big bill for legal costs after a failed libel action

During its investigation into who leaked details of Mr Mitchell's row with a policeman at the gates of Downing Street in September 2012, the Metropolitan Police accessed the phone records - the who, what, when and where of calls, but not the content - of at least one journalist on the Sun, which broke the story.

"If plebgate is an example of what goes on routinely, we ought to be worried," says Mr O'Neill.

To find the information, the Met used the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (Ripa) legislation, which governs the use of police surveillance, interception and data-collection measures.

A report, external published this week from the interception of communications commissioner found that over a three-year period, 19 police forces had sought phone data in relation to 34 investigations into illicit dealings between public officials and journalists.

That amounted to more than 600 separate applications for data - 0.1% of the total number of applications for communications records.

Andy Coulson, former News Of The World editor, was jailed as part of Operation Weeting

Mr Marshall says Ripa contains a series of checks and balances against misuse - it can be used to investigate only crimes that are "serious", and applications have to be authorised by a senior officer.

He says police must be "open to challenge" and officers must ask themselves, before they apply for "journalistic material", if it's relevant to the case under investigation.

"You have to justify what you're doing," he says.

But Mr Marshall also issues a reminder that no-one is above the law.

"Journalists have no more protection than a judge, police officer or milkman, if you're investigating serious crime," he says.

Nevertheless the disquiet over the use of Ripa has led Theresa May, the Home Secretary, to order a review by David Anderson QC, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation.

It is due to be completed by the general election, in May, when the balance between individual liberty and journalistic freedom, on the one hand, and security and effective policing on the other, will be at the forefront of the debate.

Correction: The caption beneath the picture of Andy Coulson has been changed to make clear his conviction was part of Operation Weeting and not Operation Elveden.