The forgotten interview with Cambridge spy Guy Burgess

- Published

An interview with Cambridge Five member Guy Burgess remained lost for more than 50 years after its significance was overlooked by Canadian broadcasters. It has now been discovered, as BBC Newsnight reports.

In a Moscow cemetery close to the flat he shared with his partner, Guy Burgess appeared on screen in January 1959 in his Eton tie and favourite camel hair overcoat - the very picture of an English toff.

He was appearing on Canadian television's CBC, in what is believed to be the only time one of the infamous spy ring spoke in Moscow to a Western camera crew.

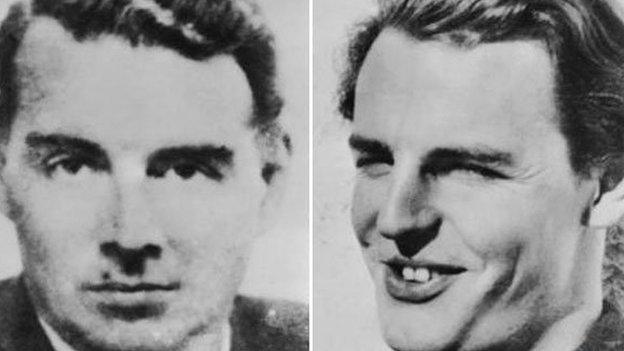

The Cambridge Five passed information about the UK to the Soviet Union throughout World War Two and into at least the 1950s.

After Burgess fled to the Soviet Union along with fellow Foreign Office diplomat and Cambridge Five member Donald Maclean in May 1951, nothing was heard of him for the next five years - although press interest and speculation in the UK and USA was particularly intense.

In February 1956 Burgess and Maclean resurfaced in Moscow when they met a couple of western journalists in a meeting organised by the KGB, but they otherwise kept a low profile.

Unreported by British press

Burgess's interview with magazine programme Close Up should have gained recognition across the Atlantic. It was a great scoop, but not a single British newspaper picked up on the interview.

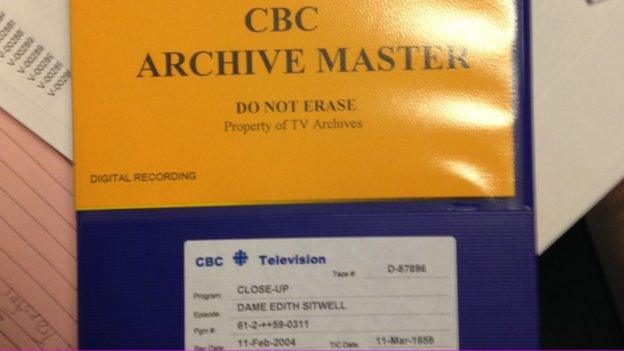

Even the programme's producers failed to realise its significance, instead being more occupied with another guest appearing on the show that same day - Dame Edith Sitwell.

The programme was originally categorised under the name of another guest, Dame Edith Sitwell

By archiving the programme under the British poet's name, Burgess's appearance went forgotten and left untouched in a vault.

Even when it was re-catalogued in 2011 under the key terms "Guy Burgess" and "espionage", its significance did not register - until CBC archivist Arthur Schwartzel stumbled across the film while helping a colleague look for material concerning the Cold War.

It was at this point CBC contacted City University London researchers Professor Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert to ascertain its validity - who, after showing it to a range of experts, were sure of its authenticity.

'Anything but sober'

So what does the tape reveal?

Well, for one, a man who was anything but sober, says MI5's official historian Professor Christopher Andrew. The spy's appearance fee was even said to have been paid in scotch.

More importantly, Burgess also outlines his desire to return to the UK to visit his family.

"I cannot imagine living in England during the Cold War. On the other hand, naturally, everybody likes his own country best.

"If the Cold War were finished I don't know what I could do. Immediately, I would rather like to go back to England for a month to see my family, but I will never do that unless I can be quite certain that I can get out of England and come back to Russia, which is where I want to live.

"Before I left [in 1951], the British government states in its White Paper that they had no evidence at all that I was a traitor, up to the time of my leaving and for some years afterwards."

Burgess was excited by an article in British newspaper Reynolds News a year earlier, which reported that there was not enough evidence for him to be prosecuted were he to return to the UK.

Evidence against Burgess at the time was small, agrees intelligence historian Gill Bennett, though files released in July last year, external describe how he handed over 389 top secret documents to the KGB in the first six months of 1945 along with a further 168 in December 1949.

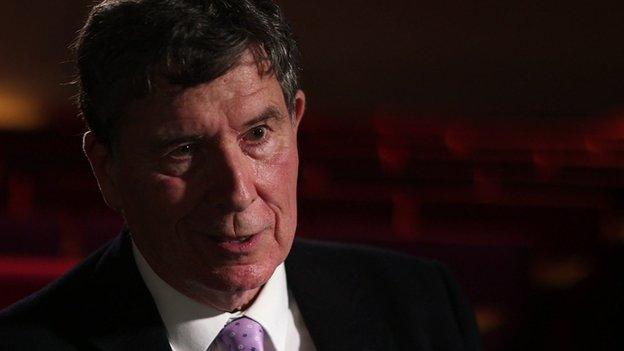

Professor Christopher Andrew believes the interview was a "shambles"

But the main reason that Burgess could not return home - which he failed to mention in the interview - says Professor Andrew, was that the KGB would not let him.

In fact, he adds, the whole interview was a "shambles".

While he believes the KGB originally allowed the interview to go ahead as a form of propaganda, it was not a success.

"Nobody is going to think better either of the Soviet Union or Guy Burgess after this interview."

This, he concludes, is most likely why "they didn't draw the attention of the British broadcasters" to the interview, and why it remained undiscovered for so long.

Watch BBC Newsnight's full report from 22:30 GMT, Monday 23 February.

- Published7 July 2014

- Published17 January 2014