Islamic State: How foreigners are helped to reach Syria and Iraq

- Published

Three schoolgirls from London are now believed to be in Syria, amid fears they are planning to join Islamic State (IS). What makes people want to travel to conflicts in foreign lands and how are they helped to get there?

Figures suggest more than 20,000 foreigners have joined the conflicts in Iraq and Syria in the last three years, with as many as 4,000 from Western Europe.

The UK has some of the highest numbers, with 500 to 600 people making the journey to join IS.

Understanding the radicalisation and recruitment, as well as the practicalities of travel to join IS, are crucial.

But predicting and tracking these individuals is often problematic.

Hard to stereotype

Foreign terrorist fighters and female "brides of jihadists" are incredibly hard to stereotype.

In addition, very little is actually known about the journey from their homes to IS territory.

However, monitoring social media platforms, tracking of online interactions and engagement with former extremists has provided the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) with valuable insight into this controversial migration.

There is no single source or cause behind radicalisation. It is a process with a variety of entry points.

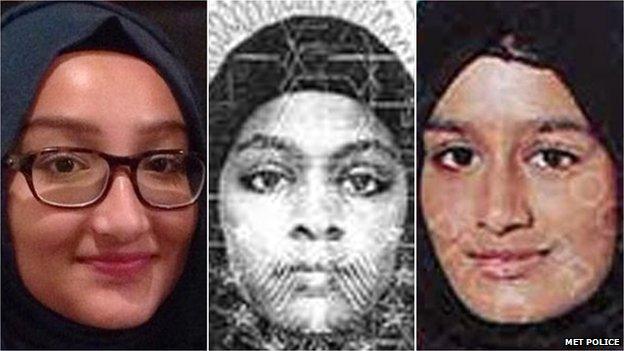

Kadiza Sultana, Amira Abase and Shamima Begum (L to R) left the UK a week ago

There are numerous socialising agents that lead people to adopt an ideology.

The same mechanisms that can attach an individual to a political party, grassroots movement or activist cause can also be used to draw individuals into an extremist ideology.

Family networks, media, education, political parties and social groups all have an influence on how we perceive our identities and ideologies - and IS has become particularly adept at manipulating these.

As a recent ISD report found, external, female Western migrants leave their friends and families in their country of origin and adopt new ones with Islamic State.

Fellow "brothers" and "sisters" of IS become the family, the media and the education centre.

IS dedicates time, money and expertise into cultivating these networks.

The online sphere acts as an access point to much of this material and is often considered a source of radicalisation.

Arguably the primary pull-factor IS has developed to recruit Westerners is its network of decentralised voices.

Other terrorist organisations have kept their internal media, information and communication highly centralised and controlled.

But IS has allowed and encouraged its foreign fighters, female recruits and supporters abroad to tweet, share and communicate their message and experiences with others on a range of online platforms.

Raqqa province in Syria has long been a stronghold for IS militants

This means that propaganda is fluent and fluid in a range of languages, targeting specific audiences through unintimidating culturally relevant spaces online.

This also means interested individuals can communicate with those that have already made their journey to IS territory, asking practical questions and receiving advice and reinforcement from those already there.

However, as research has found, offline extremist networks and recruiters remain a key "first spark" of radicalisation, introducing young individuals to online spaces which serve as a crucial catalyst to the radicalisation process.

It is perhaps no surprise that the highest number of foreign fighters from the West often derive from the countries where offline extremist networks operate.

'Echo chamber'

Al-Muhajiroun in the UK, Ansar al Haqq in France and Sharia4Belgium, to name a few, have promoted and disseminated Islamist extremist ideologies for many years.

Thus, while the first point of extremist contact is offline, the online space becomes an echo chamber, facilitating radicalisation as well as encouraging and assisting individuals to join IS.

Foreigners joining IS utilise the internet to assist their crossing.

Many already in Syria provide practical advice and encouragement.

They post on blogs, engage on public response sites, and invite interested individuals to engage on more private message streams when it comes time to plan the actualities of travel.

Questions about how to overcome the objections raised by one's family, what clothes to bring, where to attempt a crossing and what to expect on arrival are all addressed.

The practicalities of monetary currency and how to act at airports and border checks are also discussed.

Meeting points and contacts are also often organised in advance, and in some cases marriages with foreign fighters are pre-arranged.

The internet has made it effortless to go online and purchase a plane ticket.

The on-the-ground networks at Turkish and Syrian borders are less known, but there have been cases where IS has provided guides and even legal assistance to ensure that foreign recruits arrive in IS territory.

All not lost

It is clear that IS has dedicated infrastructure and thought to its robust recruitment strategy, largely depending on its online networking.

However, this is not a helpless situation.

There are myriad approaches to help stem processes of radicalisation leading to this migration.

First and foremost we must target the roots of radicalisation, rather than its symptoms.

Governments typically continue to rely on new legislation, censorship and filtering methods to counter online extremism.

Thousands have been displaced by conflict in Syria

These "negative measures" are controversial and, largely, ineffective on their own.

The focus needs to shift to "positive measures" - those that develop and propagate counter narratives and online initiatives that undermine the allure of extremist propaganda in the first place.

These measures should incorporate governments, civil society and the private sector.

Further emphasis should be paid to developing resilience to violent extremism.

This should involve improving both digital literacy and critical consumption skills, already being piloted through certain UK Prevent schemes as well as abroad.

Extreme Dialogue, for example, is a recently launched counter-narrative education programme, encouraging critical thinking in youth.

Programmes such as these serve to demonstrate that the internet is not the enemy.

Instead, it is a platform that - if developed properly - can be one of the strongest tools in the fight against extremism.

- Published24 February 2015