Can the UK afford to defend itself?

- Published

Cuts are being made to all the UK's armed forces, including the army

Events in Ukraine, and wider concern over how far Russian military aggression could go, have pushed the issue of defence up the political agenda over the last year.

The continuing turmoil in the Arab world - and in particular the horrific wars in Syria and Iraq - have further unsettled Europe's neighbourhood.

In part because of these concerns, Prime Minister David Cameron signed up to a commitment, at the Nato summit in Wales in September, external, to maintain UK defence spending at 2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Since then, President Barack Obama has lobbied the prime minister to stick to this commitment.

But the 2% pledge has not been translated into planned budget allocations. Continuing economic growth means that the UK is, on current plans, due to fall below the Nato target in 2016.

Wales summit declaration

Allies currently meeting the Nato guideline to spend a minimum of 2% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on defence will aim to continue to do so.

Allies whose current proportion of GDP spent on defence is below this level will:

Halt any decline in defence expenditure

Aim to increase defence expenditure in real terms as GDP grows

Aim to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade

Depending on how much is spent on operations, it might even fall short in the financial year starting in April 2015, when it is due to spend £37bn on defence.

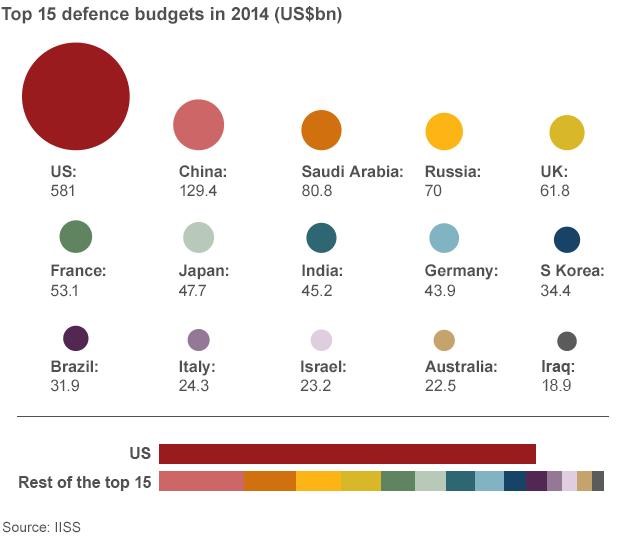

The UK maintains a powerful range of military capabilities, second only to the US in Nato. But defence has taken its share of the cuts that have already been made as part of the government's austerity programme.

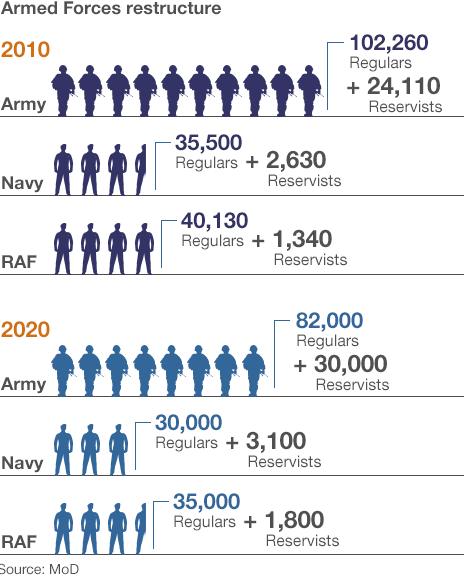

Older ships - the Invincible class carriers - and aircraft - Nimrod maritime patrol and Harrier jets - were retired before their replacements became available. Numbers of trained service personnel were cut by almost 20%, and now stand at only 145,000 in total.

When the austerity programme was launched, the government expected that it would have done its job by now, allowing the pace of spending cuts to be relaxed.

The Ministry of Defence was therefore allowed to plan on the assumption that, starting in 2015, its equipment budget would grow by a rate of 1% over general inflation every year into the 2020s. Other spending would also be protected from further real cuts.

This now seems increasingly optimistic. All the major parties are committed to protecting the real-terms budgets for health, schools and state pensions from real cuts in the post-election Spending Review.

The Ministry of Defence is the largest department without any such protection. If defence was now to be given a level of protection equivalent to those accorded for health and schools, it would require an extra £4bn per year by 2019 - equivalent to an extra penny on the basic rate of income tax.

This would allow the government to avoid a repeat of the 2010 defence review, with all the cuts in personnel numbers and equipment capabilities that this entailed.

Yet such a commitment - giving defence equal treatment with health and schools - would not be enough to meet the 2% target.

Because Nato's benchmark is linked to national income, it requires countries to increase their defence budgets at the rate of economic growth.

The recent recovery of the economy has therefore brought forward the date at which the UK will breach the 2% target.

Four on target

Defence would have to be given a further £6bn annually by 2019 (over and above the £4bn needed for real-terms protection) in order to meet the Nato target.

If the UK were to fall below the Nato target, this year or next, it would not be the only one to do so. Out of Nato's 28 member states, only four met the 2% target in 2013: the US (4.4%), UK (2.4%), Greece (2.3%) and Estonia (2.0%).

Defence correspondent Caroline Wyatt asks whether Britain's defence budget has been cut too far

Nor is there yet much sign that the other large European states - Germany, France and Italy - are planning to reach the 2% target any time soon. Only Poland seems set to join the 2% 'club' in the near future.

Even so, it will not be easy for the next British government to explain to the American president why it will not be able to meet the promise it made at Nato only a few months ago.

Not least, it will lead to particular scrutiny of any cuts that are made, and how these affect alliance capability.

Some will argue that it is time to look again at the programme to build a new generation of missile submarines, which are due to carry the Trident nuclear-armed missiles after the current submarines are retired from service in the late 2020s.

This programme is planned to take as much as a third of the equipment procurement budget by the early 2020s; and a final decision has not been made to go ahead with production of the new boats.

If the Scottish National Party and the Liberal Democrats together hold the balance of power in Parliament after the election, the programme will come under renewed scrutiny.

'More cuts likely'

Yet both the Conservatives and the Labour Party are committed to the programme, not least because of the lack of an obvious lower-cost nuclear alternative.

If significant cuts in the nuclear programme are not possible, then further reductions in the size of conventional forces are likely, even on an optimistic scenario, because of rising personnel and equipment costs.

If the defence budget is protected from further real cuts, the level of reduction could be relatively modest.

The new carriers, due to come into service from 2018, will still have to take their time to build up to their full potential capability, given the expenses involved in buying new aircraft. But it will still be a significant new additional capability, filling the carrier gap left by the current government's 2010 review.

Some further reduction in the size of the regular Army is also likely, further limiting the capability to conduct large-scale enduring operations on the scale of the recent Helmand deployment. But - provided the overall budget is protected - this may be relatively modest in scale.

If the MoD fails to gain any budgetary protection in the Spending Review, by contrast, the impact on UK capabilities would be more substantial.

While there are always efficiency savings to be made, the 10% real reduction in defence that the Institute for Fiscal Studies has extrapolated from party spending plans would be certain to eat deeply into front-line capabilities.

No matter when the Defence Review was then held, a reduction of this size would require hard decisions to be made on major programmes across all three services.

The UK's role as an international power is about diplomacy, aid and soft power, as well as defence.

And the ability of its armed forces to be a force for good depends as much on whether they are deployed wisely as on their technical capabilities.

But spending does matter - both as a symbol of the UK's commitment to common defence and - more importantly - as the necessary precondition for sustaining the high-quality forces of which the country is rightly proud.

- Published2 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015

- Published24 February 2014

- Published27 March 2014