Syria: How should police deal with those who try to go?

- Published

Three teenagers suspected of travelling to Syria were detained in the Turkish city of Istanbul this month

Four arrests in three days of young men whom police suspect of trying to head to Syria.

We don't know the full detail of the allegations in each of these cases, but the level of counter-terrorism police activity at the moment underlines that Syria is not going away.

Last year there were 327 terrorism-related arrests - more than half of them related to Syria - leading to 64 charges and prosecutions.

Not all of those cases have been under counter-terrorism laws, but they include around a dozen serious convictions relating to preparing for acts of terrorism by either trying to go to Syria or, making it there, to join jihadists.

The details relating to the arrests over the last few days are unclear.

Late on Saturday night, two 17-year-olds and a 19-year-old from London were arrested after they were deported from Turkey.

Scotland Yard, reportedly acting on information from family members, alerted the Turkish authorities to intercept the men as they arrived in Istanbul.

The three have been bailed to a later date as police carry out investigations into their plans.

The fourth teenager was arrested on Monday morning in Birmingham as he allegedly prepared to leave for Syria.

These four cases come after the disappearance of girls from east London to Syria which has led to the police facing criticism for not acting quickly enough.

Assuming detectives have the intelligence and are able to intervene in time, how should they be handling these people: charging them with crimes or finding another solution?

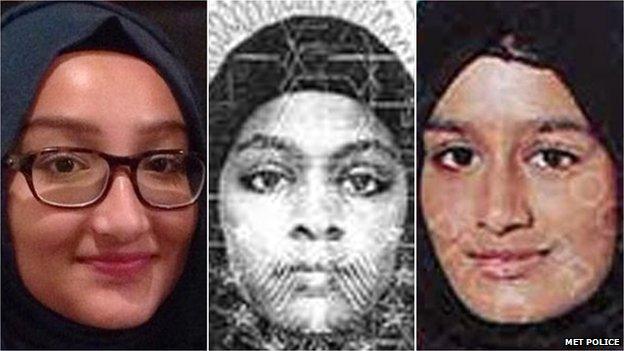

Authorities were criticised for not doing enough to stop Kadiza Sultana, Amira Abase and Shamima Begum (L-R) from travelling to Syria in February

'Open dialogue'

The police have demonstrated that in relation to Syria, they will arrest and charge if there is clear evidence that someone has committed a terrorist offence.

The counter-terrorism toolbox includes much more than a pair of handcuffs. Police can hold people at ports for questioning and the recently-passed Counter Terrorism and Security Act creates a new power to seize travel documents, including passports.

So in some cases police may try to intervene to delay and frustrate plans to go overseas because that breathing space may provide enough time for someone to start changing their mind. As we have seen in recent weeks, the police aren't always successful in stopping people going.

Beyond the legal toolkit, counter-terrorism officials are trying to find tactics to get people to stop and think. And the Home Office and police chiefs have placed a big bet on getting mothers and families more closely involved in counter-extremism work.

Police say that in the last year, 22 women and girls are suspected of having gone to Syria. They are now urging mothers to have "open dialogue with their daughters" in the hope that the early signs of radicalisation can be spotted.

There's an online campaign, external at the heart of this new call, although compared to the number of social media accounts being used by the jihadists, it is something of a drop in the digital ocean.

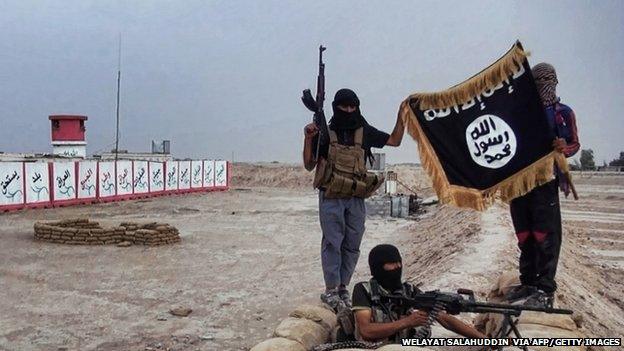

Many of those who travel to Syria are believed to have joined Islamic State fighters

'Spot the signs'

Kalsoom Bashir, the co-director of Inspire, a counter-extremism organisation, says that even if some families are scared of alerting the police about their own children, it will always be the right decision.

"In our campaigns, we are working with mothers who, at the heart of their homes, their families, can give that counter-narrative," she says.

"What we are talking to them about is being able to spot the signs that perhaps their children may be changing in their behaviour or what they are saying... and to start having conversations about what is happening in Syria and how terrorists are recruiting people from the West."

The new counter-terror laws mean that local councils will soon be ordered to set up special panels to make sure all agencies - from police to social workers - are referring vulnerable individuals into these de-radicalisation programmes.

"I think we have to reassure [parents] that if their children have not committed any crime, or terrorist activity, then they won't be charged," says Kalsoom Bashir.

"It is about keeping them from going down that criminal path.

"The cases are growing, and worryingly there is a growing number of women who are leaving and probably will do in the future as well.

"This is about making that safety net much much stronger so fewer and fewer people can slip through it. We can only do that if we start to have conversations in our homes with our families."

So the police will continue to make arrests. But there is going to be an increasing focus on the really difficult business of preventing someone being radicalised in the first place.

- Published16 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015