Westminster: Where houses earn more than people

- Published

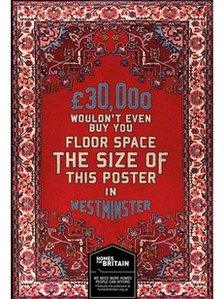

Members of Parliament heading home are greeted by a poster at the tube station that reads "£30,000 wouldn't even buy you floor space the size of this poster in Westminster".

It is a graphic reminder of the affordability crisis affecting housing in London and the South East - a disparity that has turned home owners in the region into lottery winners while those not on the property ladder are denied a roof over their head.

Research by the National Housing Federation to mark the Homes for Britain rally on Tuesday reveals that property values in England increased by £289 billion in the first three years of the current government, but £282 billion of that wealth growth (97%) took place in the capital and the South East.

The price of the average house in London, now a staggering £502,000, has been increasing each year by more than the average annual wage.

Most home-owners in the capital have seen their property earn more than they do. Small wonder that Generation Rent struggles to find anything it can afford.

In a sense, the housing crisis plays into that wider public view that Londoners, and in particular the 'Westminster-elite', are coining it - while the rest of the country struggles to pay the electricity and gas bills.

The value of property in the North West and north-east of England has fallen slightly.

All the political parties will go into the election promising answers to the housing crisis, in most cases with pledges to build many more homes.

But it takes time to produce a house, often four or five years from first planning application to the moment when the occupant walks through the freshly-painted front door. So we can be sure that the crisis is going to get worse before it gets better.

According to projections by the Town and Country Planning Association, using data from the last census, England needs 245,000 extra homes every year from 2011 right the way to 2031. Completions are currently only half of what is required and the country has already fallen more than half a million homes behind, pushing the annual demand even higher.

The reason we need so many extra homes is due to household formation: the elderly are living longer and, increasingly, in their own homes; relationship breakdown has created a big demand for more single-person homes; high levels of net-migration puts pressure on housing supply; we are living through something of a baby boom which increases demand for new family homes.

The argument that the lack of supply is now at crisis proportions appears to be shifting the public mood.

A British Social Attitudes survey published by the government last week suggests that most people in England (56%) are now supportive of house building in their local area, up from 28% in 2010.

The proportion of people who say they are opposed to new homes in their neighbourhood has fallen from 46% in 2010 to 21% in 2014.

Although public attitudes are changing, surveys suggest people don't tend to regard housing as a priority at the election.

This seems surprising given the passions the issue creates, but experts think it is because voters don't regard providing homes as a job for central government. It is seen either as something private developers should do or local authorities and housing associations.

Until that changes, our political leaders are unlikely to devote much money or energy to solving the housing crisis.