Can religion and science bury the hatchet?

- Published

Religion has an uneasy relationship with science

A new project bringing together science and religion is unlikely to end the long and sometimes bitter debate over the relationship between the two.

However, it will offer trainee priests and Christians who are scientists the chance to engage with contemporary science.

The project, external - backed by the Church of England - is to receive more than £700,000 to promote greater engagement between science and Christians, as part of a three-year Durham University programme.

Trainee priests and others will be offered access to resources on contemporary science, and the scheme will research attitudes towards science among Church leaders.

Funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the project will invite proposals for grants of up to £10,000 for "scientists in congregations" to promote greater understanding of the relationship between science and faith.

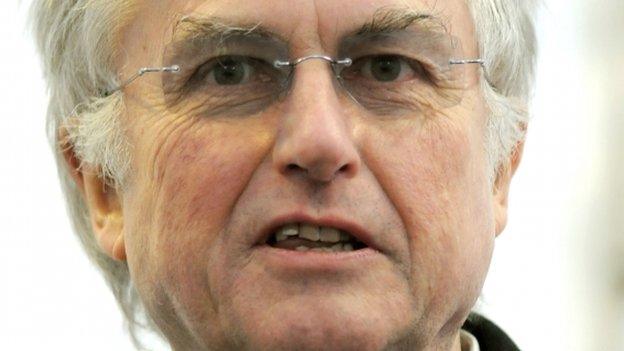

While some contemporary scientists who are atheists - such as Richard Dawkins, external in his book The God Delusion - have termed faith not credible, and even delusional, others within science do not see the two as being mutually exclusive.

One of those leading the programme is the Rev Prof David Wilkinson, an astrophysicist in the department of theology and religion at Durham University.

"Too often Christian leaders have felt that science is a threat or have felt a lack of confidence in engaging with it," he says.

Battle of ideas

Prof Wilkinson became a Methodist minister after training and working in theoretical astrophysics on the origin of the universe.

"Many of the questions that faith and science posed to each other were fruitful," he says.

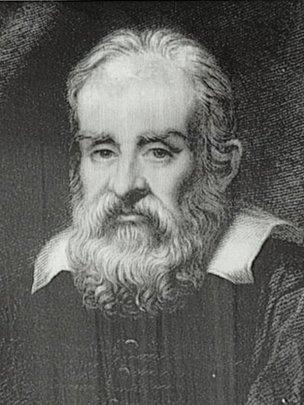

Galileo's ideas were condemned by the Church

"For many different folk both inside and outside the church, science and religion don't have a simplistic relationship - and the model that says science has to be pitted against religion doesn't explain the history of a very interesting interaction.

"Today, many cosmologists are finding that some questions go beyond science - for example, where does the sense of awe in the universe come from?"

The idea of a battle between the two dates back to the medieval Church's condemnation, external of Galileo for his discovery that the Earth moves around the Sun rather than vice versa.

It took hundreds of years for the Church to admit that Galileo had a point.

But the real narrative of a conflict between science and religion was developed in the late 19th Century, and has proved remarkably persistent - not least because it makes for lively debates on TV, radio and the internet.

Many have said that science deals with facts, while religion deals with faith, though many others today say the two have overlapping interests - arguing that both share a desire to find out what is behind the Universe.

However, more recently, arguments over creationism and intelligent design have sometimes pitted one against the other.

'Simplistic' distinctions

"The old distinction that science is about facts and religious belief is about faith is far too simplistic," says Prof Wilkinson.

"Science involves evidence, but it also involves skills of judgement, and skills of assessing evidence.

"After all, you only have a limited amount of evidence to base your theory, and you have to trust your evidence - which isn't far from being Christian.

"It doesn't involve blind faith - and indeed religion is not good religion if it is simply based on blind faith.

"Christianity has to be open to interpretation about its claims about the world and experience."

For Prof Wilkinson, the two are absolutely not mutually exclusive.

Living scientists with religious beliefs

Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web, Unitarian Universalism

Sir Colin John Humphreys, physicist, president of Christians in Science

Ahmed Zewail, 1999 Nobel Prize for chemistry, Muslim

Simon Conway Morris, palaeontologist, Christian

Martin Rees, Baron Rees of Ludlow, astrophysicist and former chairman of the Royal Society, churchgoer who doesn't believe in God

He cites The Goldilocks Enigma by Paul Davies and his idea that, like the porridge in the tale of Goldilocks and the three bears, the universe seems to be "just right' for life" in many intriguing ways.

"I've had moments of 'Wow,' like that - where you are struck by the beauty and elegance not just of the Universe but the beautiful, simple laws of physics that underlie the Universe," Prof Wilkinson says.

That sense of wonder is echoed by Catholic priest and particle physicist Father Andrew Pinsent, who worked at the Cern laboratory.

Renewed conflict

Now research director at the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at the University of Oxford, he believes it is "an extremely promising" time for research on science and religion.

However, he fears that the old "conflict metaphor" has been revived, and is shaping the way many think - especially if they have little actual knowledge of either science or religion.

Prof Richard Dawkins is scathing about religion

Fr Pinsent welcomes the idea of training priests to have scientific knowledge, saying knowledge is an intrinsic good.

"Many priests already have considerable scientific training," he says.

"For example, when I trained as a Catholic priest in Rome, 10% of the seminarians in my college had higher degrees in science and medicine, whereas the average of the UK population is estimated to be under 1.5%.

"Moreover, two of the most important theories of modern science, genetics and the big bang, were both invented by priests."

He says that as a particle physicist, he was always impressed by the discovery of "beautiful patterns and symmetries in nature, mathematics at a deep level, and the extraordinary properties of light".

"These discoveries cannot, in themselves, be used to construct a formal proof of the existence of God, but they do evoke a sense of wonder to which a religious response is natural," he says.

Other scientists agree that the long-standing idea of a war between science and religion is a misconception - though they would not necessarily see the two as natural partners.

Increased understanding

James D Williams, lecturer in science education at the University of Sussex, says: "Where we have issues, they generally revolve around people trying to reconcile science and religion or using religion to refute science.

Darwin's theory of evolution has caused acrimonious debate between clerics and scientists

"This misunderstands the nature of science.

"Science deals in the natural, religion the 'supernatural'.

"Science seeks explanations for natural phenomena, whereas religion seeks to understand meaning in life."

"In my view, science and religion cannot be integrated, that is, science cannot answer many of the questions religion poses and, likewise, religion cannot answer scientific questions."

- Published21 September 2010