Erol Incedal: The trial we couldn't report

- Published

On 13 October 2013, armed police blew out the tyres of a car near the Tower of London. That much we know for sure about the arrest and prosecution of Erol Incedal for preparing for acts of terrorism.

Since then, he has faced two trials for preparing for acts of terrorism. But what was his alleged plan?

Well, we simply do not know - and the jury at his retrial has decided it did not buy whatever it was being told he was supposed to have done.

This has been the most secret prosecution since World War Two - and it has ended with the only defendant being cleared.

A few journalists were permitted to hear to some of the secret Old Bailey sessions - but they will go to prison if they reveal what they learned.

The rest of us were allowed in to Court Nine for some brief open sessions - but most of the time the doors were locked.

Two weeks before his arrest, traffic police had stopped the 26-year-old for speeding.

He was taken to a police station for two hours - and while he was there, officers searched the black, E-class Mercedes.

They found a note inside a glasses case of the address of a property owned by former Prime Minster Tony Blair and his wife, Cherie.

In the brief public opening of the trial, prosecutor Richard Whittam QC alleged Incedal had been considering a range of options for a terrorist attack, including against an "individual of significance" or, perhaps, a gun attack on the streets, similar to that in Mumbai in 2008.

During the first trial, these allegations were left hanging in the air.

In the second, the court was told Incedal had allegedly met a British jihadist called "Ahmed" on the Turkish-Syrian border earlier in 2013 and this second man had asked him to do something in the UK.

They allegedly exchanged coded emails relating to Mumbai and Kalashnikov rifles.

But here is the problem. Incedal denied the allegation - and the Crown's case was not fully detailed in open court. There was no cross-examination in public that helped the public to understand what the evidence amounted to.

We do not even know if either of these allegations were at the core of the case or, perhaps, peripheral to something else said behind the closed doors.

Was Tony Blair the individual of significance or just one of a number of possible alleged targets?

One part of the case was clear. Incedal had a memory card hidden in a phone case, and it contained bomb-making plans.

Incedal was convicted of possessing this document at the end of the first trial.

His co-accused, Mounir Rarmoul-Bouhadjar, also admitted having the same document.

Surprisingly, the clearest evidence came from a normally secret source.

The security services had bugged Incedal's car - and the jury heard recordings that sounded like he was downloading and watching jihadist battles in Iraq.

During one discussion he talked about getting a gun and bullets, using the code "sausage and sauce".

He said he hated white people, praised Islamic State commanders, and, briefly, talked about being in Syria's mountains.

Black flag of Islamic State - seen from the Turkish side of the border with Syria

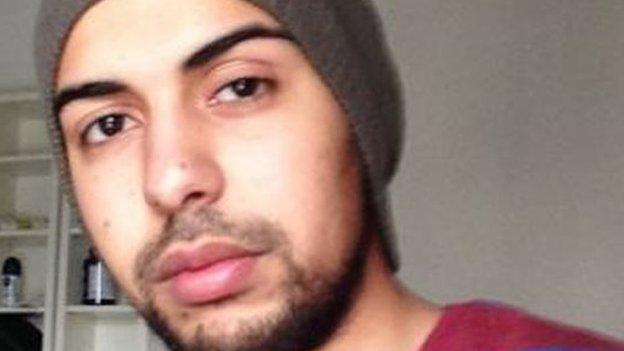

Incedal was no stranger to the region. Born in Istanbul, his late father was a member of a Kurdish Communist group in Turkey.

Years later, his much older sister was killed fighting alongside Kurdish separatists.

He was raised in London by his mother. She is an Alawite Muslim, the same ethnic group as Syria's ruling elite.

Incedal was excluded from school, convicted of petty crime and married at 17. He became a father of two and had various business plans - but none accounted for his flashy lifestyle.

Israfl Erbil knows the family well - and says that Incedal lacked a father figure in his life.

"It was difficult to get communication with Erol because he was acting apart from the community and the family," he says.

"He was not a calm person, difficult to call him... he has his own mind and ideas."

So what was Incedals's defence?

He told the jury in the open proceedings he had been planning an armed robbery - he said he had been going to try to enlist three sons of the radical cleric Abu Hamza a-Masri. He denied wanting a gun for terrorism.

But time and again, the open evidence left us with unanswered questions.

How secret was the secret trial?

First trial autumn 2014. Jury failed to reach a verdict on preparing acts of terrorism

Second trial in February - March 2015

Approximately 68 hours of evidence

10 of them in open and public court

28 hours of secret evidence heard by "accredited journalists" - but remains secret until a legal ruling otherwise

30 hours of evidence heard in complete secrecy before judge, lawyers and jury

When the defendant's car was first stopped for speeding, Incedal had apparently "made demands" the police could not accommodate.

During questioning after his arrest, detectives stopped the interview so they could digest a handwritten statement from the suspect.

The contents of that statement have not been read in open court.

And from the witness box in the first trial, the defendant said he had a reasonable excuse for carrying a memory card containing bomb-making plans.

The BBC's man on the inside was senior producer Jeremy Britton who co-ordinates our coverage of the Old Bailey.

He is not allowed to tell any of his colleagues anything about the evidence he heard or saw in some of the secret parts of the trial.

"On a typical day we would wait around for a couple of hours outside court," he says.

"A policeman would come out and gives us 10 seconds to hurry in.

"We hand over our telephones to the policeman that are then put in a metal box and locked up.

"We then collect our 'secret' notebooks from a metal safe, and then we walk in front of the judge and the jury in total silence to our desk and start writing.

"After about 20 minutes we would do the whole thing in reverse.

"I've worked at the Old Bailey for 15 years, and I have never come across anything like this before.

"It is totally unique - and I wouldn't want to repeat it."

Co-accused: Mounir Rarmoul-Bouhadjar admitted possessing bomb-making plans last year

The Times's crime and security editor, Sean O'Neill, was also on the inside. He says the enforced secrecy ran against the basic instincts of every reporter.

"It's been very difficult," he says.

"I have always been unhappy with the idea of being an 'accredited journalist' - accredited by the state to cover a trial. I have become more and more uncomfortable with that as the process has gone on - particularly this business of handing your notebook to a counter-terrorism police officer every day and having it locked in a safe.

"It's a deeply unhealthy process.

"There is a lot that we have heard in court that should not have been secret and should be aired in public and scrutinised.

"They can take your notebook away, but they can't take this stuff out of your head.

"The key facts are there and I'm itching to write them."

Lord (Ken) Macdonald QC is the former Director of Public Prosecutions. He oversaw a string of major terrorism trials - but none of them ever required this kind of secrecy.

"It would be disastrous if we moved into a world where courts were more routinely going into closed session," he says.

"Public confidence in the criminal justice system requires transparency and openness.

"The people have to be able to see what's happening in the courts.

"They have to be able to see the evidence that leads to convictions, and I don't believe that people will have confidence in the decisions of the courts if we allowed too much secrecy."

The jury has heard all 68 hours of evidence and has cleared Incedal of the main charge he faced.

He still faces jail for his conviction on the lesser charge of possessing a document useful to terrorism.

For those of us on the outside, we heard less than a one-seventh of the case.

There were tantalising glimpses of the full story: chinks of light into a dark process that nobody other than those behind the closed doors could understand.

- Published26 March 2015