British jihadists: The friends who want to be martyrs

- Published

Abu Qa'qa "jumped" to join two friends who travelled to Syria to fight

"If you get captured you need to blow yourself up because if you get captured they won't mess about. They will break your bones. They will beat you up."

These words are greeted with laugher from a group of British men.

They can be heard chatting and one, with a northern accent, is talking about his recent experience of being wounded in his first battle.

His right leg was fractured when it was penetrated by a bullet fired by a Syrian soldier - many miles from the young man's home in Manchester.

His companions laugh again as he recounts the moment when he grabbed hold of a bomb belt, believing his death was close.

The wounded man, who is doing most of the talking in a conversation that was recorded and posted online last year, is referred to by his alias - Abu Qa'qa.

It is believed he is Raphael Hostey, a university student from Manchester.

A judge recently said he had "become an inspirational figure encouraging others to travel and join in with jihad" in Syria and Iraq.

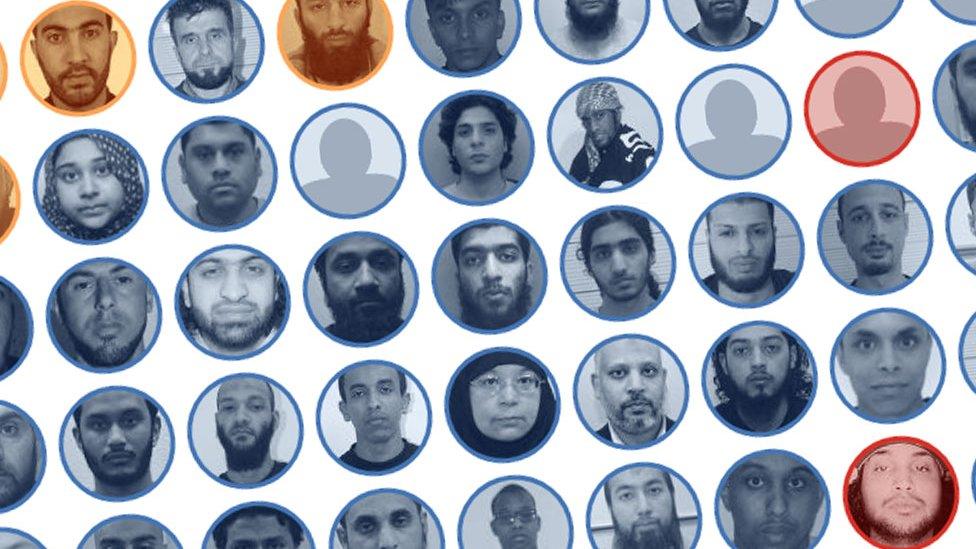

Ifthekar Jaman (left) and Khalil Raoufi (far right), a friend of Raphael Hostey, are fighters believed to have died

What the case of Abu Qa'qa demonstrates is the important role played by friendship groups in this conflict.

The men who can be heard chatting and joking about their violent experiences are bound together by the feeling that they are "brothers in arms".

And, crucially, their journey from Britain towards the pursuit of martyrdom on the battlefields of Iraq and Syria often began within their friendship groups at home.

In a blog from Syria, Abu Qa'qa describes how he felt frustrated during the early days of the Syrian conflict "seeing picture of our brothers and sisters dying and injured… whilst we all remained behind with talk rather than action".

He recounts how he and his friends would go round in circles discussing what to do. Meanwhile he was facing pressure from his parents to complete his degree.

He describes the key to his decision to go to Syria being the day when "two brothers came to the decision of leaving… As soon as I heard about this I jumped towards them in excitement".

'Real-world connections'

Court papers show Hostey left his wife and young child behind to team up with fellow students Khalil Raoufi, Mohammed Javeed and a fourth friend from Manchester, Nur Hassan - all of them just out of their teens, hungry for action.

They were all mentioned at the trial of Jamshed Javeed, a biology teacher from Manchester who helped them travel to Syria to fight.

Jamshed Javeed, who had planned to go to Syria himself, was jailed earlier this month for terrorism offences.

Ifthekar Jaman, whose face can be seen, is one of hundreds of Britons to have gone to Syria or Iraq to fight

Shiraz Maher, senior fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King's College London, which tracks the movements of foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, said: "We talk a lot about the internet but these are people with real-world connections."

He said the internet and social media "play a role" in inflaming opinion, but "it's in the real world where the motivation, the logistics, come into play".

This is borne out by research conducted by BBC News, which shows the existence of geographical clusters from where friends and - in some cases - relatives have gone from Britain to join the jihad.

Six friends left from Portsmouth, one of them later joking that they could form their own brigade called the "Bangladeshi Bad Boys". Four are now dead and one is in prison.

Shiraz Maher, who was in contact with some of them, told the BBC: "They were a close-knit group of friends, united around the same sorts of ideas.

"They were broadly conservative Muslims and engaged in street preaching in their hometown… they decided to take collective action."

Another group of three teenage friends from Coventry also took collective action.

They left their families in the spring of 2014. Within weeks they were active on social media, posting material in support of Islamic State (IS).

Two are now dead, leaving heartbroken families behind.

In east London, Birmingham and Cardiff, too, there are other clusters of friends who have joined the jihad in Syria and Iraq.

Marc Sageman, a national security expert who worked for the CIA and has written and advised governments on the problem of radicalisation, said: "These are not crazy kids.

"They feel they share the same fate. Like many young people they have their fantasies."

He said humans are "social animals and they do everything based on friendship and kinship" and points to the "failure of these kids to identify with British national identity".

"They see Britain as engaged in a fight against them," he said.

He said that would be compounded by recent attempts to criminalise some of those who had travelled to Syria and Iraq.

Spreading the word

Aimen Dean - a founder member of al-Qaeda who recently spoke publicly for the first time about his role as an undercover agent for MI5 infiltrating extremist networks - said the "counter-narrative is confused and not coherent… calling these people criminals will not do anything".

He pointed to the strong currents drawing people to the conflict, the "appeal of being able to serve what's seen as a noble cause" - building a new state.

He said pro-IS propaganda encouraged young Muslims to believe they were part of a unique project to reconstitute the Islamic caliphate.

They were made to "feel wanted" and that they would be "held accountable by God if the project fails because if it fails it is a sin on you", he said.

Once they were in Syria or Iraq, Mr Dean said, the Western recruits received more religious instruction from their new tutors.

Then they are given back their phones and told to contact their friends back home and spread the word.

Responding to claims that treating those who travel to fight in Iraq or Syria as criminals was not an effective strategy, a Home Office spokeswoman said: "Our priority is to dissuade people from travelling to these areas of conflict and the Prevent strategy, external is working to identify and support individuals at risk of radicalisation."

But she said those who travel "for terrorist activity should be in no doubt that we will take the strongest possible action to protect national security, including prosecuting those who break the law".

- Published12 October 2017

- Published5 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published17 December 2013