What is misconduct in public office?

- Published

Under Operation Elveden the CPS has prosecuted 29 journalists

Misconduct in public office is an ancient common law offence, created by judges, which can be traced back to the 13th century.

Applying it to the 21st century news media involved the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) striking a balance between the freedom of the press to probe and find out what is happening on the one hand, and protecting and maintaining impartial and incorrupt public services on the other.

It has always been a difficult balance.

For many years some journalists have paid public officials for information.

In 2003 Rebekah Brooks, then editor of the Sun, told a committee of MPs that News International had paid the police for stories.

The phone-hacking scandal, which led to News of the World royal editor Clive Goodman being jailed, was a "game changer" in the practice of public officials being paid for stories

For decades the practice was largely ignored or tolerated.

The phone-hacking scandal proved to be a game changer.

In early 2007, when the News of the World's royal editor Clive Goodman and private investigator Glenn Mulcaire were jailed for phone hacking, the true extent of the practice was not exposed - despite copious evidence of it.

The criminal justice system failed.

When it was revealed in 2011 that the phone of the murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler had been hacked, the system kicked into action.

A fuller and broader investigation, Operation Weeting, rigorously investigated the practice.

Evidence was given to the police by News International's "management and standards committee", set up to investigate internal business practices in the wake of the hacking revelations, which showed that some of its journalists had also made corrupt payments to public officials.

Operation Elveden was established.

Reasonable excuse

This time law enforcement was determined to investigate and prosecute the misdeeds of the press with rigour.

The Sun's Neil Millard is one of the 13 journalists to have been acquitted under Operation Elveden

For the offence of misconduct in public office to be prosecuted, a public official has to misconduct himself to such a degree as to amount to an abuse of the public's trust in his office, without having a reasonable excuse or justification.

Prosecution guidance focused on whether there was a strong benefit to the public interest in the story.

Applying this and other guidance, the CPS decided not to prosecute 14 journalists but did prosecute 29 others.

In this context, the offence itself is essentially one of bribery, and it criminalises both the giver and the taker of the bribe.

However, only one Elveden conviction against a journalist now stands.

Thirteen others have been acquitted, including last month four senior figures at the Sun.

In recent trials juries simply did not seem keen to convict the giver of the bribe, the journalists.

Expensive prosecutions failed and that put pressure on the CPS.

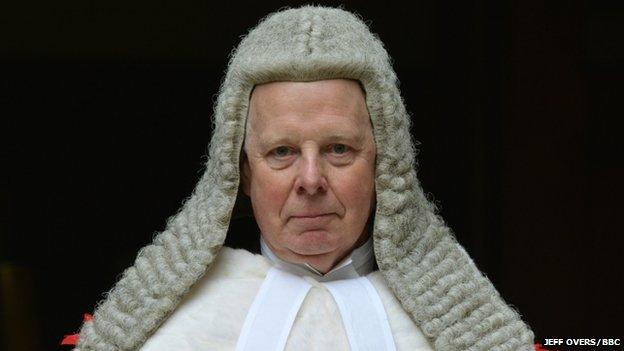

A ruling by the Lord Chief Justice emphasised the high threshold of seriousness needed to prosecute the offence

However, it was the intervention of the Court of Appeal that has led to today's change in prosecuting policy.

In March the Lord Chief Justice Lord Thomas gave judgement in two appeals against conviction in Elveden cases.

His ruling emphasised the high threshold of seriousness needed to prosecute the offence.

Critically, it also said that more consideration should be given to the potential harm, or lack of it, to the public interest in the disclosure of information, as opposed to relying on the strong benefit to the public interest in any resulting story.

A subtle but important difference.

Simmering fury

Under the new guidance, sustained corruption of police officers is seen as particularly grave.

The police have access to confidential databases with information about suspects, victims and witnesses.

A journalist who corrupts a police officer over a period of time would certainly face prosecution.

However, it may not be in the public interest for journalists paying other public officials to be prosecuted.

Here the degree of harm to the public interest by the corrupt payments and lack of harm caused by any story that results from it, may mean it is not appropriate to prosecute.

The CPS has accordingly amended its prosecuting guidance and dropped many of the Elveden prosecutions against journalists.

It may claim that this is a result of the normal development of the law where prosecutors amend their policy in response to Court of Appeal judgements.

However, the very press that has been on the receiving end of CPS decisions to prosecute its journalists, will not be so kind in its assessment.

A simmering fury at the treatment of those arrested and prosecuted for paying money to the likes of prison officers for stories is about the erupt.