Rapid escalation of the cyber-arms race

- Published

The potential damage from cyber-attacks is rapidly becoming more extensive

Codenamed Locked Shields 2015, Nato officials say it was the "most advanced ever live-fire cyber-defence exercise".

Four hundred cyber-warriors from 16 countries last week responded to a scenario, external in which computer networks came under attack from another state's hackers.

The scenario was based around the idea of "hybrid conflicts", just below the level of war, in which one state both carries out espionage and disrupts the communications and operations of another, tied in with other activities.

The countries portrayed in the scenario were fictional, but it is hard to interpret this as anything other than thinking about Russia, which is seen as having pioneered hybrid conflict in Ukraine and, before that, Georgia.

The exercise itself was taking place in Estonia, which was subject to its own cyber-attack, external.

But the ability to carry out significant - even destructive - cyber-attacks is spreading rapidly: all part of a cyber-arms race accelerating rapidly not just between Nato and Russia but also beyond into other states and even non-state actors.

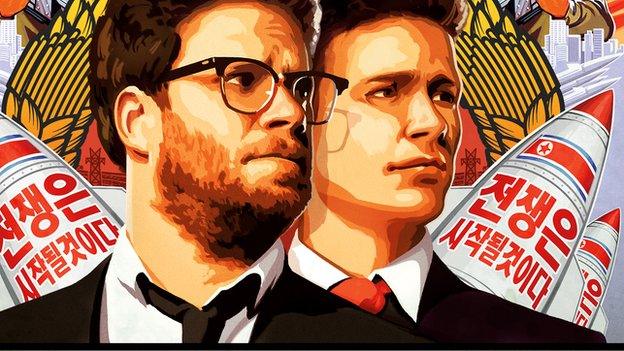

Just before Christmas, Sony Pictures got hacked.

Physical damage

The intrusion was attributed by the US to North Korea and linked to the release of the studio's film The Interview, in which North Korea's leader was featured as being killed.

The cyber-attack did not only expose embarrassing corporate secrets but also wiped company computers, rendering them as useful as a brick.

Computer espionage has been happening for years, but the destructive element was another sign that states are increasingly willing to deploy malware that does real physical damage and to link their cyber-attacks to physical threats (in this case against cinemas showing the film).

In North Korea's case, cyber-weapons are a vital part of the country's arsenal.

The film The Interview is thought to have provoked a cyber-attack on Sony

"Cyber-hacking is a crucial part of their asymmetric military capabilities. They have been pursuing it for such a long time with unbelievable levels of concentration, support and investment," says Kim Heung Kwang, a former computer science professor in North Korea who left for the South.

"That's how they have been able to foster this in such a lopsided shape compared to everything else in the country."

He says a military unit that had 500 personnel when it started in 1998 has now grown to more than 3,000.

This kind of wiper attack, which renders computers unusable, was first seen on a large scale in 2012, when staff at the oil company Saudi Aramco, external tried to switch on their computers.

US officials believed this attack was, like the Sony hack, state-sponsored, in Saudi Aramco's case by Iran.

But, if so, it was almost certainly simply a response to attacks on Iran itself - including most famously the Stuxnet virus, external, which damaged Iranian centrifuges over an extended period and is widely believed to have been the joint work of the US and Israel.

Stuxnet virus:

Stuxnet was first detected in June 2010 by a security firm based in Belarus, but may have been circulating since 2009.

Unlike most viruses, the worm targets systems that are traditionally not connected to the internet for security reasons.

Instead it infects Windows machines via USB keys - commonly used to move files around - infected with malware.

Once it has infected a machine on a firm's internal network, it seeks out a specific configuration of industrial control software made by Siemens.

Once hijacked, the code can reprogram so-called PLC (programmable logic control) software to give attached industrial machinery new instructions.

Rapid proliferation

What surprised cyber-experts is the speed with which cyber-attack capabilities are now proliferating.

No-one was surprised that the first tier of cyber-states - the US, UK, China, Israel and Russia - were capable of carrying out destructive attacks on infrastructure, but the speed with which others - such as Iran - were able to do the same has caused consternation and is a sign of how far cyber-attack can be a force-equaliser between different nations who might otherwise have wildly different capabilities.

Cyber-attacks have the potential to shut down cities

Capabilities are also spreading to non-state actors. Criminals have long used ransomware to extort money from people or else see their computers locked.

But terrorist groups may also now be toying with more than just low-level disruptive attacks that deface or take off-line websites.

France's TV5 Monde saw the real-world effects of a cyber-attack when it was taken off air, external by people who claimed to belong to the "cyber-caliphate" affiliated to the group calling itself Islamic State.

There are fears the use of destructive attacks against industrial control systems - like Stuxnet - could also spread.

Closing down a city

At a recent Cyber Security Challenge, Dr Kevin Jones, from Airbus, showed me how a model city connected up to the internet could have its power switched off remotely.

"Unless we put a security architecture in place, this is very possible," he says.

A German government report said a steel mill had been damaged, external by a cyber-attack last year - the perpetrators were unknown.

Dr Jones believes the attackers got in through the regular corporate infrastructure, although it is not clear how far they deliberately targeted the control systems for the blast furnace that was damaged.

When it comes to the cyber-arms race, are Western countries still in the lead?

Some argue the top end of cyber-espionage tools may well still be in the hands of the US.

The security firm Kaspersky Labs, for instance, recently revealed the work of hackers they called the Equation Group, external, who were highly sophisticated.

Edward Snowden raised the public profile of Britain's cyber-activities

"The Equation Group are masters of cloaking and hiding," says Costin Raiu, director of the Global Research and Analysis Team at Kaspersky Labs, pointing to the ability of the group to get inside the firmware of machines and then launch highly advanced attacks.

"This is insanely complicated to be honest," he says.

Kaspersky Labs will not directly point the finger, but the widespread assumption is that the Equation Group is linked to America's National Security Agency (there are links with the codes used in Stuxnet as well).

Documents released by the American whistle-blower Edward Snowden have also raised the profile of Britain's cyber-activities.

"GCHQ has formidable resources," says Eric King, of the group Privacy International, whose concern lies in the lack of a transparent framework of accountability over offensive hacking.

"In the last year and a half, we've seen their malware. The depth of the work and where they are going is very formidable."

He says: "We have non-existent policies, practices, legal safeguards to oversee this." (GCHQ always maintains its activities are lawful and subject to oversight).

Commercially available

Another concern is the way in which such some of these cyber-espionage capabilities are now commercially available and being used by more authoritarian states.

"Companies are providing surveillance as a consultancy service," says Mr King, who adds foreign law enforcement and intelligence agencies can then use the bought services to hack dissidents and activists based in the UK.

The capabilities may be spreading to more and more actors but a small handful of states still operate at the highest level.

One senior Western intelligence official believes the Russians are already ahead of the US and UK - partly because of the level of resources, mainly people - they throw at finding and exploiting vulnerabilities.

That official, of course, may be bluffing, but they also said they did not think it would be long before the Chinese had also not just caught up but moved ahead.

- Published6 March 2015