Human rights law is Gove's big challenge

- Published

Winston Churchill wanted to safeguard human rights after the World War Two

The new Justice Secretary Michael Gove is known to be courteous, charming, and confrontational.

He is likely to have to call upon all of those very different qualities in meeting the thorniest challenge nestling uncomfortably in his in-tray.

Hot from the Conservative manifesto, is the pledge to scrap the much disliked, much misrepresented and much admired Human Rights Act, external (HRA) - it really depends what newspaper you read.

The manifesto, external says: "The next Conservative government will scrap the Human Rights Act, and introduce a British Bill of Rights.

"This will break the formal link between British courts and the European Court of Human Rights, and make our own Supreme Court the ultimate arbiter of human rights matters in the UK."

The 1998 HRA incorporates the European Convention on Human Rights, external (the Convention) into domestic law, enabling all of us to enforce our human rights in our own courts.

The HRA requires British courts to 'take into account' judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

The Human Rights Act has provoked much controversy

There is much debate as to just how binding that makes Strasbourg's judgments - completely, significantly or not really that binding at all, more part of an interesting dialogue with our own judges.

However, the UK was signed up to the Convention long before we incorporated it into domestic law in the form of the HRA.

The Convention was the child of Winston Churchill's desire to enthrone human rights in the aftermath of their horrendous abuse during the World War Two, and was drafted by British lawyers.

Minor or fundamental change?

Scrapping what the prime minister has called "Labour's Human Rights Act" in favour of a British Bill of Rights could be attempted in a way that makes a relatively marginal change in Human Rights law and has little effect on the UK's international reputation.

Alternatively, it could amount to a seismic change which takes the UK outside the Convention and into a human rights netherland with Europe's sole remaining dictatorship, Belarus.

Conservative manifesto pledge on Human Rights:

"We will scrap Labour's Human Rights Act and introduce a British Bill of Rights which will restore common sense to the application of human rights in the UK.

"The Bill will remain faithful to the basic principles of human rights, which we signed up to in the original European Convention on Human Rights. It will protect basic rights, like the right to a fair trial, and the right to life, which are an essential part of a modern democratic society.

"But it will reverse the mission creep that has meant human rights law being used for more and more purposes, and often with little regard for the rights of wider society.

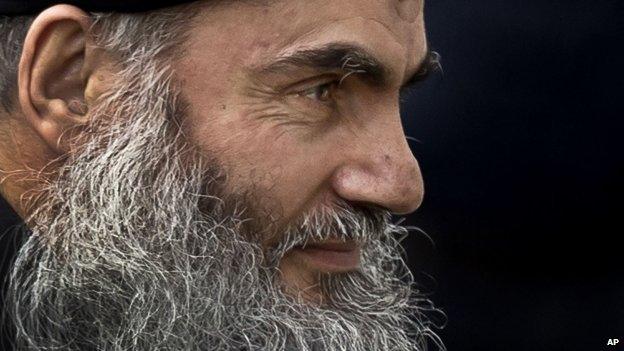

"Among other things the Bill will stop terrorists and other serious foreign criminals who pose a threat to our society from using spurious human rights arguments to prevent deportation."

A British Bill of Rights which incorporates the HRA with a bit of "plus and minus" could meet the manifesto pledge to scrap the act, without heralding major change.

On the plus side, there would perhaps be a right to jury trial, and a right enshrining the freedom of the press.

Last October, the Conservatives published plans for changing Britain's Human Rights laws in 'Protecting Human Rights in the UK, external'.

It identified problems with Article 8, external, the right to a private and family life.

The application of that right in the courts was seen as a block on deporting foreign criminals and the issue has undoubtedly infuriated many people.

There is a concern that it is just too easy for those who have broken the law and who don't deserve its protection, to shelter behind the right.

Whole-life sentences

The paper also cited Article 3, external, which provides protection from the risk of torture or inhuman and degrading treatment.

It was applied by Strasbourg in its ruling that whole life sentences without the possibility of review, were unlawful.

Abu Qatada deployed Human Rights legislation to fight deportation from the UK

That issue has been resolved in a dialogue of judgments with our own Court of Appeal.

Whole life sentences can and are being imposed on the most heinous murderers.

So, on the minus side, the British Bill would undoubtedly place limits on the right to family life.

Critics of the government's plans might well accept some qualifications here.

Limitations on Article 3, would be far more problematic and contentious.

But how would a British Bill of Rights relate to the European Convention on Human Rights?

Convicted murderer Arthur Hutchinson argued his whole life sentence infringed human rights legislation

Would it alone "break the formal link" between the British Courts and Strasbourg?

Presumably the government is content for there to be an informal or less formal link with the court?

The Bill could provide for judgments of the ECHR to be advisory only.

Different set of rules

That would mean that the UK would be playing by a different set of rules from the other 46 member states in the Council of Europe, the international organisation which is NOT to be confused with the EU, but which promotes human rights across all 47 of the council's member states and runs the Strasbourg court.

A further problem here is that it is not just the Human Rights Act which compels the UK to "take into account" Strasbourg rulings.

New Justice Secretary Michael Gove faces tricky negotiations

Article 46 of the Convention states that: "The High Contracting Parties undertake to abide by the final judgment of the Court in any case to which they are parties."

In other words, we're bound to take Strasbourg's rulings into account under the HRA, and if we scrap that, we're still bound! Not sure everyone has quite grasped that one.

In October the Conservatives said they would "engage with the Council of Europe, and seek recognition that our approach is a legitimate way of applying the Convention".

So maybe there is a pragmatic solution?

Perhaps the Bill would include a provision for some oversight of Strasbourg judgments - a parliamentary committee which acts as a filter between the court's decisions and any legislative change?

Symbolically breaking the direct link with the Court, but in reality doing little new.

Rowing back?

The October document went on to say "in the event that we are unable to reach that agreement, the UK would be left with no alternative but to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights".

That threat didn't make it into the manifesto, an omission seen by some as a rowing back on what would be the seismic reform option.

Some Conservatives want to depart from the Convention and see the British Bill as the first step in that process.

That would entail leaving the Council of Europe and joining Belarus as Europe's only human rights outsiders.

Even Russia which has shown scant regard for its obligation to follow judgments from Strasbourg, has never threatened to depart the Convention and leave the Council.

Former Attorney General Dominic Grieve was a critic of Conservative plans for reform

Assuming that Mr Gove decides to go for the less drastic option, a sort of moving of the human rights deckchairs to make them more British in feel, he will nonetheless be mindful of his wafer-thin Commons majority.

That means getting on board those Conservative critics like former Attorney General Dominic Grieve QC and former Justice Secretary Ken Clarke QC.

A sherry and a pint of bitter may be waiting for them in the Commons Bar as the first "liquid" step in a Gove charm offensive.

Oh, but even with the party fully onside, there is one further giant legal and constitutional vipers' nest for Mr Gove to negotiate.

The human rights in the Convention are a key part of the devolution arrangements with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In the latter case they are enshrined in the Good Friday agreement, an international treaty.

If those rights are changed will that mean that the devolution settlements need to be amended - and just how do you go about that?

Or would there be a fracturing of human rights in the UK, with different versions in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?

At a time when cohesion of the Union is a political priority for the government, that doesn't seem a very attractive option.

Possible delay

So, how quickly will Mr Gove move? Not very, I suspect.

There is in existence a draft Bill of Rights which the former Justice Secretary Chris Grayling promised would be published before the election. It wasn't.

There is a strong argument for delaying it until after the EU referendum.

As important as Human Rights reform is, to tackle it before the UK's membership of the EU is settled, would be putting the political cart before the much bigger political horse.

Mr Gove might conclude that, despite the best efforts of some to make it so, Human Rights reform is not a totemic issue of public concern.

It will be very interesting to see if the reforms make it into the Queen's Speech on 27 May.

A pint and a sherry say maybe they won't.

- Published3 February 2015