Anis Sardar trial: Iraq bombmaker trapped by sticky tape

- Published

Sergeant Randy Johnson died after taking the full blast of a homemade bomb

Taxi driver Anis Sardar has been convicted of the murder of US Sgt Randy Johnson, who was killed by a homemade bomb while on patrol in Iraq eight years ago, and it was a piece of sticky tape that gave him away.

Driving through a thick cloud of dust thrown up from a dirt track, a convoy of American military vehicles was patrolling the countryside west of Baghdad in September 2007.

The tension had risen inside the Stryker armoured personnel carrier as soon as they had turned off the main road.

Platoon leader Sergeant First Class Randy Johnson, on his third military tour of duty, was looking through the hatch above him for signs of buried bombs ahead.

Soft surfaces are easier for insurgents to hide improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and what the soldiers called "moon dust" made Sgt Johnson's task near impossible.

'Painstaking evidence'

As it passed over a bump, the bottom of the Stryker scraped the surface of the track and was suddenly torn apart by the force of a bomb blast. Gunner Elroy Brooks, sitting in the rear, was catapulted 15 metres out of the vehicle.

Sgt Johnson had been standing above where the bomb detonated. His comrades dragged him on to the roof of the Stryker for medical attention but, despite their desperate attempts, he died.

Jurors were shown a photograph of the damaged wheel area of the US armoured vehicle

They also saw a picture of a pressure plate used to activate one of explosive devices found in 2007

The conviction of Anis Sardar comes almost eight years since the events of that bloody day during a conflict which has seen many such terrible acts of violence.

Tragic though it was, on the face of it there was nothing unusual about what occurred on that dusty track amid the abandoned farmland beyond the outer edge of Baghdad.

And yet this was an American soldier killed by a British bombmaker who has been brought to justice - in the first case of its kind - thanks to painstaking forensic evidence gathered from the scene and then analysed by scientists in America and Britain.

Fingerprints matched

Parts of the bombs, including the one which killed Sgt Johnson, were sent to the FBI's Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Centre in Quantico, Virginia, where a massive warehouse houses tens of thousands of IEDs from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Forensic scientists extracted fingerprints from four devices that Sardar's bombmaking team had assembled.

In early 2014 they matched prints on two of the bombs to Sardar. This was possible because when he had re-entered the UK after fleeing Iraq in 2007, Sardar was questioned by officers at Heathrow Airport. Although he was not arrested, his fingerprints were taken.

American scientists also found on each of the devices, including the bomb which killed Sgt Johnson, the fingerprints of fellow bombmaker Sajjad Adnan who was briefly detained by American forces but whose current whereabouts are not known.

So although Sardar's prints were not found on the lethal bomb, he was convicted of the murder as part of a joint enterprise with Adnan: their four bombs being very similar in design and placed very close to each other.

'University dropout'

In court, Sardar drew a picture of himself as an academic failure who had dropped out of university, and dabbled with drugs and clubbing before discovering his faith.

He claimed he had spent a decade living in the Syrian capital Damascus, learning Arabic and Islamic Sciences, but never quite finishing a degree.

While there, he said he had become horrified at the consequences of the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Thousands of refugees flooded into Syria with accounts of sectarian killings, kidnappings and the torture of Sunni Muslims by Shia militias.

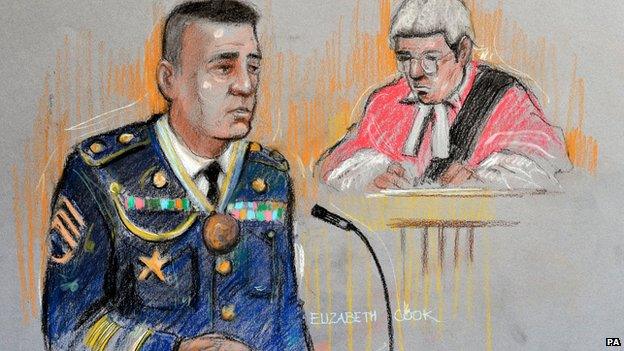

Anis Sardar "watched impassively" as some of the survivors described the attack in court

Sardar told the jury at Woolwich Crown Court that he went to Iraq in early 2007 for a few weeks to help an Iraqi friend extract his family from the turmoil. He repeatedly broke down in tears as he recounted what he had seen.

He admitted spending an afternoon helping a group of men in a village assemble IEDs, describing how he was asked to wrap tape around bomb components.

He denied knowing where they would be planted but said they were to defend Sunni villagers from sectarian attacks by Shia militia.

'Chaos and horror'

However, the jury agreed with the prosecution that Sardar was a jihadist whose main enemy in Iraq was the Americans, not the Shia militia. He worked in a cell making bombs that were then buried under roads that were regularly patrolled by US forces.

They were sophisticated devices with pressure plates attached, designed to trigger detonation only when heavy military vehicles passed over them.

Some of the men who survived the attack on the Stryker testified in court against Sardar. He watched impassively from the dock as they described the chaos and horror of that September day.

US Army Staff Sergeant Mark Aggers, who served as a gunner on the Stryker, gave evidence

During his cross-examination by the prosecution it emerged that shortly after Sardar returned home from Iraq he worked for three or four years as a volunteer, offering support to young Muslims held in Feltham Young Offender Institution in west London.

Around this time his house was raided by counter terrorism police. Though he was found in possession of a compact disc containing instructions on the manufacture of explosives, he was not charged.

After that, he seems to have settled down into family life and started work as a black cab driver but his past finally caught up with him when scientists in an American lab pulled his fingerprint off a piece of sticky tape he had used to bind parts of a bomb together.

- Published29 April 2015

- Published28 April 2015