Why are there so few forced marriage prosecutions?

- Published

Last year the Forced Marriages Unit (FMU), run jointly by the Home Office and the Foreign Office, gave advice and support in 1,267 cases of possible forced marriages.

So why are there so few prosecutions?

Many say the problem lies in deep-rooted cultural traditions and that young people are reluctant to come forward to the authorities.

Nazir Afzal, former head of the North West Crown Prosecution Service, says the new legislation with the threat of seven years in prison is needed to make progress.

"One of the major things stopping victims coming forward is the codes of silence that exist in the family.

"It's like the mafia. You cover up, as you are so scared of the consequences," he says.

"Victims are not receiving the justice they deserve and this is why this new legislation matters. It's to help victims - it's all victim-led."

Campaign groups say the actual numbers of forced marriages are much higher, with between 8,000 and 10,000 each year in the UK, though this remains an estimate and actual numbers are hard to prove.

Mandy Sanghera, a human rights activist, told the BBC: "Families still hold on to cultural practices.

"Parents still regard family honour very highly. They may have promised their daughter at a young age and given their word, but feel that they cannot go back on it."

Common beliefs

She also said many young people facing a marriage they did not want were reluctant to come forward to the authorities, for fear of seeing their parents go to prison.

"We are talking about family - your blood, your ancestry. You hold common cultural beliefs. You just don't do something that would put your family in jail."

Figures from the FMU suggest that the majority (79%) of young people forced into marriage are girls. Of those whose age was known, 39% were under 21.

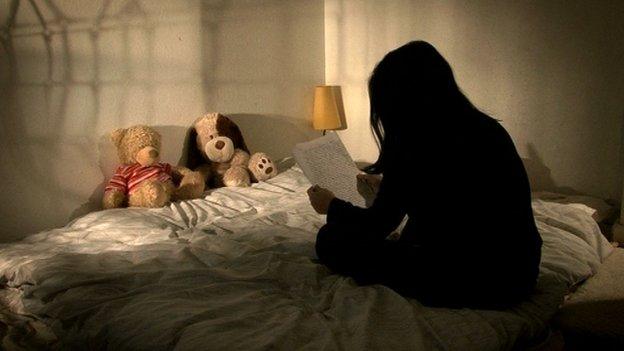

Often young girls are under huge emotional pressure from their families.

The FMU was involved in cases covering 88 countries, with most from the Asian subcontinent, external - 38% from Pakistan, 8% from India and 7% from Bangladesh.

About a quarter were solely within the UK, with no overseas element.

Legal doubts

Some campaigners have doubts about the forced marriage legislation.

Rani Bilku, of Jeena International, external, a community group based in Slough, Berkshire, says: "Challenging and changing hearts and minds from voices within communities is the answer, as opposed to shouting from the outside and legislation."

The code of family honour and shame can run very deep in families with strong roots on the subcontinent.

Nazir Afzal says: "When victims go to the police it's seen as even more dishonourable and the consequence can be murder so they just accept their fate."

Some parents claim to believe they are doing the best for their child in arranging their marriage and that they are helping them to secure a good future.

Shaista Gohir, of Muslim Women's Network UK, says: "They prioritise their ties abroad and the happiness of their nephews and nieces (often children of their brothers, sisters and cousins) over and above the happiness of their children.

"In fact they sacrifice the happiness of their own children for their extended family."

- Published26 January 2015

- Published28 May 2015

- Published13 June 2014