Three ways secret data collection fights crime

- Published

- comments

A massive report on the future of the UK's investigatory powers has been published.

David Anderson QC, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, calls for a complete rethink of the current framework that allows agencies to collect communications and data - and says the laws need to be "comprehensive and comprehensible".

Ministers want to extend current powers - but critics such as campaign group Liberty say that the proposals amount to a "snooper's charter", external.

Just to be clear - the powers themselves shouldn't necessarily be characterised as secret because they are set out in legislation. But the actual techniques devised thanks to those laws are.

So how are the existing powers actually used?

Intercepting the conversations

Interception means using intrusive techniques to listen in or read real communications. In the old days of black and white television, that meant opening mail or tapping a phone line. In the modern world, the principle could be applied to all manner of communications.

David Anderson's report, external explains how intercept can be used to break drugs gangs.

In one case, police were running a major investigation into escalating violence between rival gangs across London.

Intercept was at the heart of the operation. That could mean the police were listening in to mobile phones, but who knows - that's just speculation.

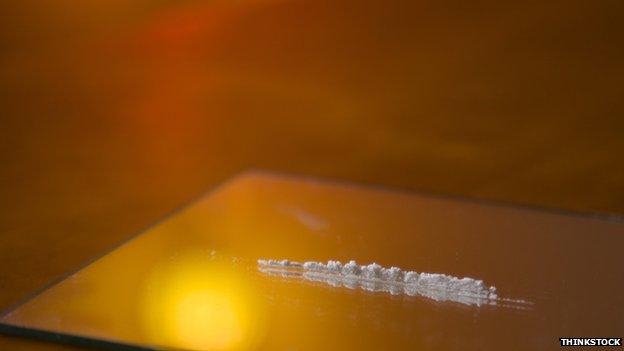

The important part is this. The intercepts told the police an awful lot more about how the groups were organised, what they were seeking to do, how they were considering using guns, the identities of key individuals in the drugs supply chain, junior members used to deliver the goods and, ultimately, a location where the bulk product was kept.

Police took that intercept evidence and began building a criminal case. The intercepts revealed the kingpin was planning to shoot a rival - and he ended up being arrested while en route with a loaded gun.

Over the course of the operation, police arrested 100 people, seized 40 firearms, more than 200kg of Class A drugs and £500,000.

Intercept evidence is used in some country's criminal courts - but British intercepts are not used in our trials. There's a long-standing ban on their use because security chiefs fear that their use in evidence would ultimately lead to the disclosure of techniques and sources - rendering them unusable.

GCHQ: Central to UK's data surveillance operations

Collecting "bulk data"

More than half of the intelligence reports that are produced by GCHQ, the UK's eavesdropping agency, including instances of bulk interception.

This is where there is a warrant to collect lots of information as part of an operation where one or both of the senders or recipients is based overseas. GCHQ can seek a warrant to collect this information - although it must also explain if it is going to end up collecting private information of people unrelated to the operation.

Now, depending on your position, bulk collection is either mass surveillance or "target discovery" - security jargon for fishing for bad people you previously didn't know existed.

This type of interception has played an important role in terrorism investigations. Rajib Karim was a software engineer at British Airways. But he was also working for Anwar al-Awlaki, an American-Yemeni preacher who played a key role in recruiting people to extremism until he was killed in a drone strike.

He was initially identified by GCHQ analysts - prompting a major and complex police investigation to uncover evidence that he wanted to use his airport access to launch an attack.

In another case. GCHQ analysis revealed how four Luton men had made contact with al-Qaeda in Pakistan. That initial lead sparked a police investigation back home, leading to their conviction for preparing for acts of terrorism.

A group of Luton men were jailed after investigation sparked by communications data analysis

Using existing data records

"Retained data" is information that is already collected, such as for telephone billing, which the police or intelligence agencies can use to piece together events in the past. This kind of material regularly features in criminal trials - it was a key feature of the evidence in the News of the World mobile phone hacking investigation.

But it can also bring killers to justice. Stuart Ludlam was a taxi driver found dead from two gunshot wounds in 2009.

Derbyshire Police began looking into the last number to contact him through the taxi company. The call came from a pre-pay Sim card which was not registered to anyone - but they worked out that it had been topped up at a petrol station.

These investigations ultimately led them to the killer.

Retained data has also played a key role in solving international abuse. In 2008, FBI investigators were sifting online images of abuse and found a file that linked to two abusers in the UK.

The link was established because the imagery had been shared by email - and that included the technical details that pointed towards the location of the computer that sent the file. The recently passed Counter Terrorism and Security Act means that British internet service providers can now be ordered to keep a record , externalof how their customers were connected and when.

This is different to logs of actual activity - and David Anderson has said in his report that the authorities need to work harder to make the case for a power that wide.

- Published11 June 2015

- Published18 April 2013