Mind the gap - bridging news inequality among the public

- Published

Audiences are increasingly getting their news via social media

Let us start with two observations, emerging both from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report, external and daily life in the newsrooms of the BBC.

One is that the world is changing both more quickly and more slowly than we expected.

On the one hand, smartphone use is revolutionising the news, particularly for younger people.

On the other, TV bulletins and radio programmes are the way millions of people prefer to get the news - and will be for years to come. (Indeed, the BBC's TV news audiences are holding up surprisingly strongly in the UK and growing, rapidly, around the world.)

The other is that the digital future is fabulous, but it is not fair. The internet is enabling us to tell more stories in more engaging ways to more people than ever before.

But there is a widening information gap between people online and those offline, an emerging generational divide in news consumption, a greater imbalance in reporter numbers between news organisations and uneven patterns in the fewer stories that seem to get ever bigger audiences and the many more that do not.

For any news organisation, but particularly for the BBC, these two trends present a singularly difficult challenge: how do we keep everyone informed?

We all need reliable information to make good decisions - for ourselves, our communities, the country we live in and the world we share. How do we best serve traditional media habits, while anticipating new ones so that everyone can access the real story?

Information inequality

In January, the BBC published the first part of a report on the Future of News. It set out a range of views about what is happening in the news industry as a whole - and what changes in technology, people and stories might mean for news organisations in the next decade.

The report made the case that, for all of the benefits of digital growth - and there are many - this is an age of growing information inequality.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee said: "Around 40% of people in the world use the web so for the other 60%, every time the power of the web increases and it's possible to do more things online, those 60% are left further behind.

"To a certain extent, the web is increasing the gap between the have and the have-nots."

I will not dwell on inequality relating to digital access as this is a digital report.

Information inequality takes many other forms - with people less well informed because the news industry speaks to some groups in society more than others, because the modern media offers ever more alternatives to the news, because people are overwhelmed by communications or because the nature of the internet and, in particular, social media, can sometimes lead them to an incomplete picture.

The findings from this year's Digital News Report offer further support to the idea that there are growing inequalities, even amongst those who do access the internet for news.

Not everyone accesses news online

Generational divide

The world increasingly divides into those who actively seek out the news, and those who skim or even avoid it.

When it comes to news consumption, we saw in our Future of News work that the information gap between younger people, poorer people, and some ethnic minority groups on the one hand, and older people, richer people, and some groups of white people on the other, is widening.

A generational divide has always existed within news. In the 2015 Digital News Report, 86% across the countries said they get the news at least once a day - but this falls to 75% amongst 18-24s and rises to 92% among those aged 55+.

A change in the way young audiences consume the news is already well under way and, in the last year, has accelerated.

Younger audiences are turning away from TV news bulletins, and towards mobile (and increasingly, online video and new visual formats).

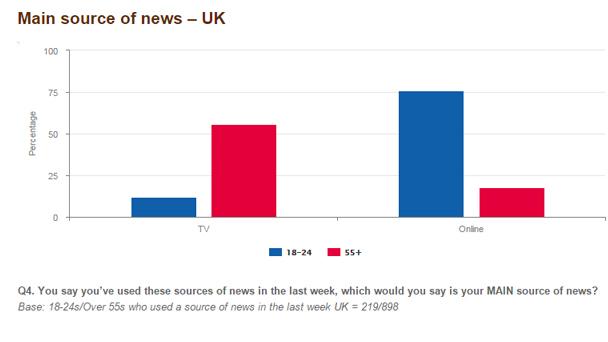

In the UK, 56% of over 55s said the TV was their favourite news source, compared with just 12% of 18-24s (76% of this younger age group chose online).

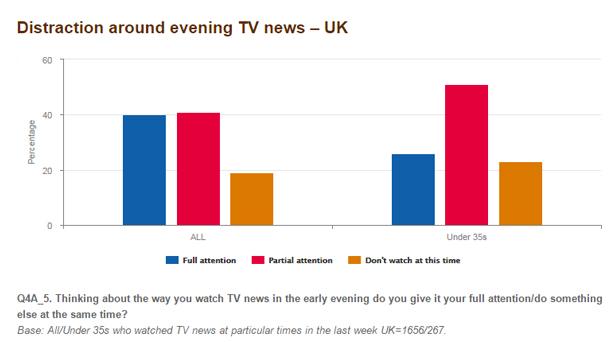

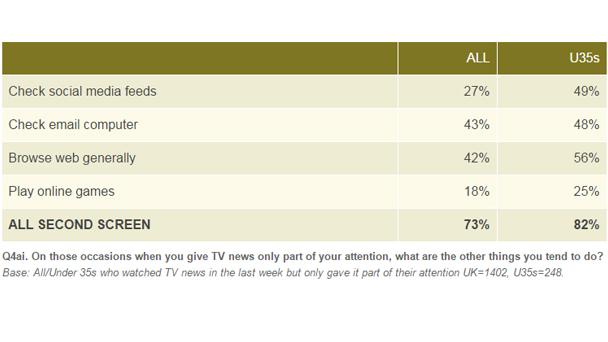

Even when watching TV, the second screen can be a distraction to attention - half of those who watch TV news said they are regularly distracted by other things (higher amongst under 35s) and eight in 10 under 35s (82%) said this distraction is from a second screen (emails, social media, web browsing).

This year's data shows a quickening towards mobile news-use overall, with the smartphone emerging as the central platform for digital news.

What does the rise in smartphones and decline in TV mean for attention and engagement with news?

Within use of BBC News on mobiles, we see more skimming, with shorter session durations - although there could be changes in future, with the 2015 Digital News survey showing the proportion overall saying they read stories online having risen (overtaking just reading the headlines) and online news video also up (now 31% amongst 18-20s).

Different gateways to news

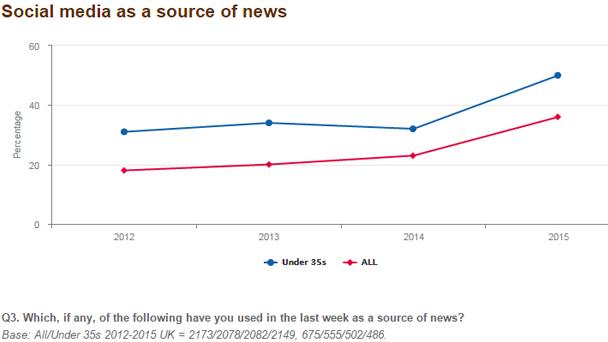

Audiences are increasingly getting news via social media. In the UK, the percentage of those using social media as a source of news has risen significantly in the last year - up from 23% to 36%.

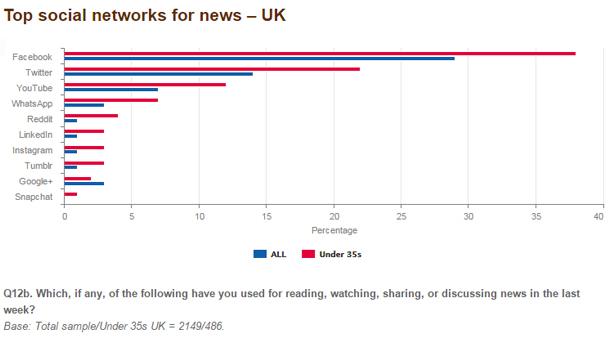

This year, we also see an increased role for Facebook in how people find, discuss and share news. WhatsApp and Instagram have further cemented Facebook's position with young audiences.

The increasing importance of search and social as gateways to news has raised concerns over the degree to which it gives users a filtered view - and Emily Bell at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism has pointed out that the internet is not necessarily a neutral curator of the news.

That said, this year's survey has new data that suggests news-users tend to feel that these services help them find more diverse news and lead them to click on brands they do not normally use - and news organisations see the huge value of social media in reaching audiences less likely to come to news websites.

Addressing information inequality

It is clear than the growth of digital is overwhelmingly beneficial to audiences and news organisations. But the internet is not keeping everyone informed, nor will it. And news organisations - particularly those with a mission to serve a universal audience, like the BBC - must try to address that gap.

To do that, the BBC's oldest values are key to its future: trust - rooted in a commitment to accuracy, impartiality, diversity of opinion and fair treatment of people in the news - is the BBC's most prized asset.

It is what will make people come to the BBC in the ever noisier marketplace for information on the internet.

But we will also need to experiment - in what we do, in how we look, in how we sound. We will need to be even more open to having content on other platforms.

We will have to keep on innovating in our storytelling. We will have to give much more power to people to select, scrutinise and shape the news.

This year's Reuters Institute Digital News Report will focus minds. It will also underline two headaches.

The first is caused by the need to meet the enduring requirements of old media habits, while racing to get ahead of the possibilities of new platforms.

The second brought by the need to embrace the exciting possibilities of news in the internet age, without losing sight of the information gaps it is creating.

To keep everyone informed - i.e. to fulfil the democratic purpose of the news - we will have to grasp both broadcasting to mass audiences and personalised services streaming to the individual; both breaking news in quick snaps as well as investigations, analysis and reporting that have the benefit of time and slow consideration; news for both big screens on the wall and small ones in the hand.

Our aim, though, is singular: to be the place people come for the real story - what really matters, what is really going on, what it really means.

In the internet age, the mission of BBC News remains the same - to inform.

- Published16 June 2015