Lord Janner: Case puts spotlight on legal options

- Published

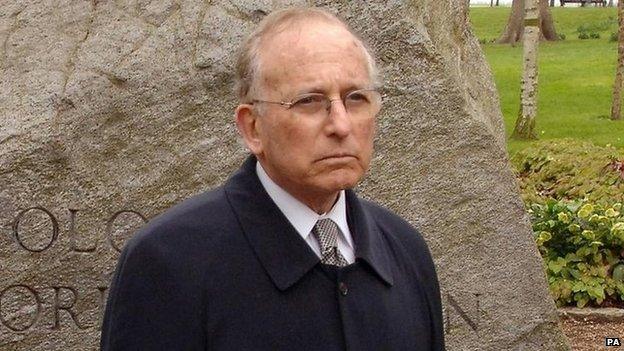

A decision not to bring criminal proceedings against Lord Greville Janner has been overturned by an independent QC.

It has come about as a result of the Victims' Right to Review system.

The Director of Public Prosecutions, Alison Saunders, has said she made the "right decision" not to prosecute Lord Janner over child sex allegations, saying his dementia was so severe that he could "play no part in a trial".

This Crown Prosecution Service review system has only been around for a couple of years and is a very democratic means for victims to review decisions of prosecutors not to charge alleged defendants.

Review guidelines

Under the system, the director of public prosecutions is treated in the same way as any other prosecutor.

The Crown Prosecution website says: "The review will comprise a reconsideration of the evidence and public interest i.e. a reviewing prosecutor, independent of the original decision, will approach the case afresh to determine whether the original decision was right or wrong."

In the case of Lord Janner, Alison Saunders' decision was not based on the evidence that Lord Janner committed the alleged sexual offences - that was sufficient for there to be a realistic prospect of a conviction - but on the application of the public interest test.

She decided that, based upon the medical evidence of irreversible dementia, it was not in the public interest to prosecute Lord Janner, who was not fit to take part in any proceedings.

It has never been part of our criminal justice system to force those who lack mental capacity to take part in criminal trials where they cannot understand the proceedings or instruct their lawyers.

Lord Janner and his family have always denied any wrongdoing.

Trial options

There are two ways to determine whether a person is "fit to plead" i.e. mentally capable of taking part in criminal proceedings.

It can be determined by the CPS as it was here, or it can be done by a judge.

If he decides Lord Janner is fit to stand trial, a normal trial will take place. If he decides the peer isn't fit, there can be what's known as a trial of the facts, with a jury.

Alison Saunders has defended her decision not to prosecute Lord Janner

This is a little used process governed by the Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964.

The word insanity gives a clue as to the purpose of a trial of the facts.

It is used when a court needs to impose a hospital or supervision order under the Mental Health Act on a defendant who lacks mental capacity.

So, it would be used, for example, in a murder case where the defendant lacks capacity, and needs to be hospitalised to protect himself and the public.

In order to do that, the court has to establish that the accused did the physical acts of the crime. It cannot go into the mental elements i.e. intention or any of the defences to the charge.

Three outcomes

There are only three possible outcomes from a trial of the facts. They are a hospital order, a supervision order or an absolute discharge.

The jury can only make a finding that the defendant did the particular physical act. There cannot be a verdict of guilty.

Such a trial recently took place in the case of the former Luton South MP Margaret Moran, who was accused of falsely claiming more than £53,000 in parliamentary expenses.

She was given a two-year supervision order.

In Lord Janner's case, the process would involve the alleged victims giving evidence.

Lord Janner, pictured here with Tony Blair, has done nothing wrong, his family say

This might be done by the jury seeing video evidence of something called the "achieving best evidence" interviews, given by victims to specialist police officers.

This is fairly standard in cases of serious sexual offences and is designed to avoid the trauma of having to give live evidence of the events.

Legal opposition

However, the victims would then be cross-examined by defence counsel live - although special measures are available so that evidence can be given from behind screens or by a video-link to a room outside the courtroom itself.

A trial of the facts would most likely be strenuously opposed by Lord Janner's legal team, who would argue it was an abuse of the court process to subject him to any sort of trial where there had been so much adverse pre-trial publicity.

They might argue that, in his case, the publicity was especially adverse as the media might have thought, following the DPP's original decision, that there would never be any sort of criminal trial.

Lord Janner's legal team could also try to judicially review the decision to bring proceedings. They would have to persuade a judge that the decision to bring proceedings was so unreasonable as to be unlawful.

- Published24 April 2015

- Published21 April 2015

- Published17 April 2015