Analysis: What's happening with knife crime?

- Published

- comments

Former knife carriers tell the Victoria Derbyshire programme why they did it

What's going on with knife crime? Wasn't this an offence of the past - one that haunted a succession of home secretaries and chief constables but was now contained and controlled?

Knife crime never went away - it just fell quite a lot and, correspondingly, out of the headlines.

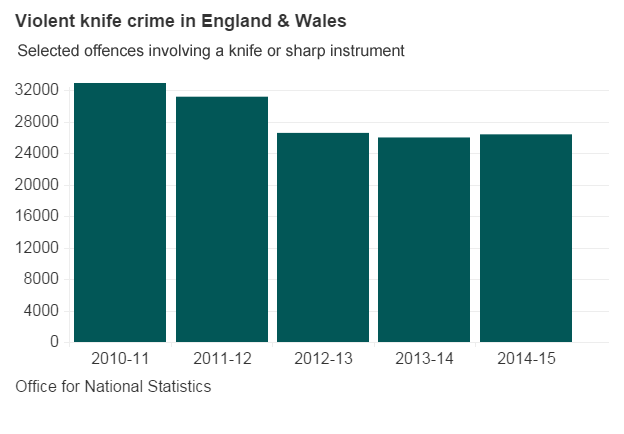

Now figures from the Office for National Statistics have shown that knife offences in England and Wales rose by 2% in the year to March 2015. While that sounds small, it masks a really complex and concerning picture that raises important questions about why it's going up again and whether the police tactics are right.

Knife crime hit a record in 2008 and the then government launched a major initiative - the Tackling Knives Action Plan (TKAP).

In each of the initial 10 areas, police officers were dedicated to long-term operations to identify the knife-carriers through a surge in intelligence-gathering and, correspondingly, a co-ordinated use of stop and search powers.

With intelligence pointing at increased use by gangs, officers would target places where they would hang around - and many young offenders were put into a special youth justice programme designed to challenge their knife-carrying behaviour.

Did TKAP work? A 2011 Home Office study, external showed that there had been falls in serious violence by teenagers or young adults right across the country, irrespective of whether or not they lived in a TKAP area.

Had it been a waste of time and money?

Not so, says Chief Constable Alf Hitchcock, the national lead on knife crime.

"There was an awful lot of stop and search and it had a massive impact. We saw a 32% reduction [in knife offences] in 12 months. We correlated that with the hospital data and we could see that it was having an impact on offender behaviour."

He argues that, with hindsight, TKAP probably had a deterrence effect beyond the target areas. Increasing numbers of carriers around the country decided it wasn't worth the risk tucking a blade into their waistband.

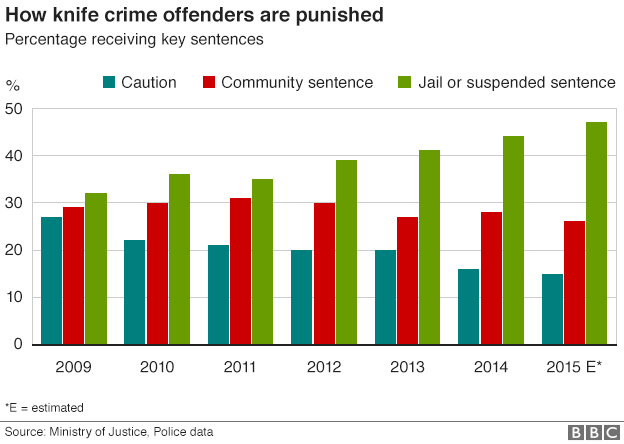

Speaking of deterrence, what about sentencing?

In 2012, a new law of aggravated knife possession was created to squarely target those definitely carrying a weapon for crime and threatening to use it.

Along with the new law came minimum sentences and, today, people convicted of knife-related offences are increasingly likely to go to prison.

During TKAP, police chiefs floated the idea of a mandatory sentence for anyone caught carrying a knife twice.

That law finally comes into force on Friday after Labour and Conservative MPs formed an informal coalition last year to see off Liberal Democrat opposition to the measure.

Against all of that, the 2015 rise in knife crime is grim reading. The signs of a statistical U-turn began appearing last year - and last month figures showed a definite rise in injuries in London.

The latest ONS figures show an increase in recorded assaults, external - up 13% to almost 14,000 - and a 10% rise in possession offences to just over 9,900 crimes. Robberies involving knives are, however, down 14%.

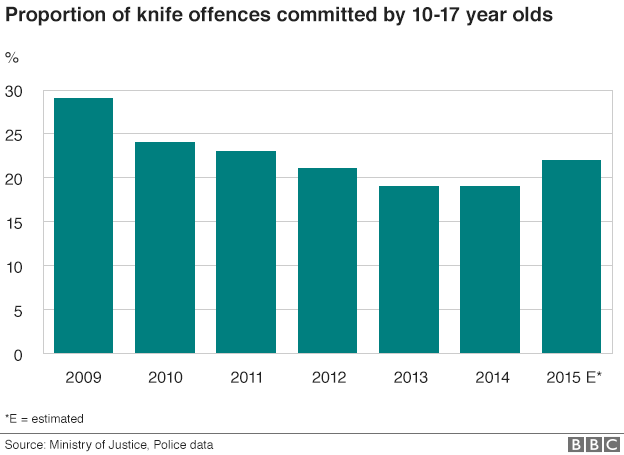

Separate figures show that while knife offences are up, the proportion of 10 to 17-year-olds involved in the crimes has been falling - until now.

The big question, ultimately, is how do the police get on top of all this - which is where we come back to the question of stop and search.

Research and police intelligence tends to categorise knife-carriers in a number of ways. There are those who are carrying a knife to commit a crime. Then there are a group who are carrying because they see their mates doing it.

Police chiefs who support the stop-and-search led strategies developed under TKAP believe that it remains the most important tool for dealing with the first two categories.

But stop and search has been falling after the home secretary told forces to rethink how they're using it. She said nobody wins when it's used poorly - particularly if used unfairly against young black men.

So has a fall in stop and search caused a rise in knife crime? Have the carriers decided it's worth the risk carrying a blade once more?

The Met's commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, appears to think so and his officers are stepping up how they are using the tactic.

There is one final group who carry knives - those who say they do so "for protection".

A lot of police officers believe this is a convenient excuse rolled out ad nauseum in the interview suite.

But critics say that repeated governments have failed quite miserably to understand what lies behind gang culture.

And, they argue, no amount of visible policing or stop and search is going to break a rather depressing state of fear in the minds of some young people.

- Published16 July 2015