Are IS recruitment tactics more subtle than we think?

- Published

How exactly does the so-called Islamic State radicalise young Muslims over the internet? The experience of one British teenager, who claims to have turned many others away from IS, reveals tactics similar to those employed by groups who seek to normalise anorexia and self-harm.

Sajid opened a fake Twitter account about a month after his brother disappeared. Arshad had never shown any signs of radicalisation, or of being particularly interested in the Syria conflict, but the evidence was plain to see.

His bed was empty, his passport gone. His school had not seen him. His laptop's search history showed a host of IS-related content. Then, Arshad contacted Sajid from Syria to say he, like hundreds of other young Britons, had decided to become an IS fighter.

Sajid, who was 16 and still at school in London, wanted to know more. Using a false Arabic name he took from a TV programme, he opened a Twitter account and began searching "Isis" (an alternative name for IS) and "Syria" and following relevant accounts.

Immediately, he was followed back by an IS supporter. A brief exchange of tweets followed before Sajid logged out. He had homework to get on with.

Instant followers

Two hours later, when he went back to Twitter, he found he had amassed about 5,000 followers.

Many Twitter chats followed, and, eventually, he became close to six online contacts, whom he would message regularly.

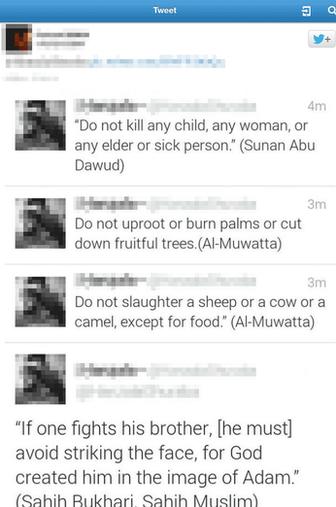

A series of tweets by Sajid. Al-Muwatta is a collection of hadiths (teachings)

Some were in Syria, others were IS supporters in the West. They were "surprisingly supportive" given that Sajid had been clear he rejected his brother's actions.

"Surprisingly, no Isis supporter actually told me to come [to Syria] or even to support Isis," Sajid tells me, in a series of exchanges over an encrypted messaging app.

"This was a shocker for me. I expected them to push me to come. To this day, I don't know why no-one actually told me to support Isis."

His experience conflicts with the popular view of IS recruitment, that, like paedophiles or online fraudsters, its operatives are lurking online to ensnare and recruit vulnerable young men and women.

The picture Sajid paints is less one of sinister puppet-masters pulling young innocents to the centre of a web - more that of a delusional but self-supporting community seeking affirmation in each other. It is not dissimilar to online communities devoted to celebrating anorexia, self-harm or conspiracy theories.

Groups like this function by attracting people with a common interest who encourage each other to share pictures and videos about their fixation. As they do so, the behaviour they celebrate becomes normalised.

Yet through open networks and private messaging apps, he was exposed to a constant stream of propaganda. Much of it focused on the persecution of Sunni Muslims at the hands of Iraq's Shia Muslim-dominated security forces, followed by the retribution of IS fighters.

To Sajid, it seemed the chief attraction of IS for most of his online contacts was the notion of "payback" for Sunnis against Shia atrocities, and the feelings of empowerment that came with it.

"I started to watch the videos and I became heart-hardened," he said.

"After reading about Shia crimes against local Sunnis, I remember watching a video of an execution of an Iraqi soldier and thinking, 'Good.'"

But this moment became a turning point for Sajid. Hatred was being stoked in his heart, and with it, sympathy for IS.

Shamima Begum, 15, who left London for Syria is thought to have been radicalised, at least in part, over the internet

"This shocked me afterwards," he said.

"I questioned my conscience, and my results were that I did not support Isis with my heart at all. I decided to stop watching the videos."

In effect, Sajid had realised he was being radicalised, just like his brother.

"I thought to myself, 'Is this what my brother felt? Maybe he's right and I'm wrong.'"

But his brother's experience meant Sajid was "more aware of the circumstances if I'd joined a terrorist group".

"Somewhere it is a personal choice to be honest," he said.

"When my bother went, I had seen the impact it had on my family.

"My little siblings refusing to eat, no sleep et cetera.

"So I knew that would be their fate again if I decided to do that.

"I don't think my brother had the idea of how my family would get torn apart from his stupid decisions."

It's difficult to say how typical Sajid's experience of radicalisation is. After all, when he first announced himself online, it was as the brother of suspected IS-recruit. However, Sajid can put himself in the place of others who are less self-aware.

Deleted tweets

"I think there are levels to radicalisation," he said.

"Imagine a young Muslim boy thinking that [Iraqi] soldiers are getting away with murder, then Isis comes along and tells them, 'Come fight for the caliphate, and we'll help you get revenge.' It will be the guy's dream."

Among Sajid's contacts were two IS fighters in Syria who would update him constantly via instant messaging app Kik.

As a result, he became something of an authority, with supporters asking him for news and even travel advice.

As he became more aware of his status as an "insider", he began to portray a more pro-IS line, while still being determined to prevent others from following his brother's footsteps.

"One of the biggest challenges I faced, was pretending to be an Isis supporter and still trying to tell people not to go," he said.

"Once, a Somali girl living in London messaged me and told me... she was thinking of going [to Syria].

"My response was, 'What? Don't be stupid? Don't go.'

"I think she replied, 'What the hell? Are you a spy or something?'

I actually got scared. I feared she would broadcast this to Isis on Twitter. Thank God, after two minutes she deleted the tweets.

More from BBC News

At least 700 people from the UK have travelled to support or fight for jihadist organisations in Syria and Iraq, British police say. This BBC News database details the stories of those who have died, been convicted of offences relating to the conflict or are still in the region.

"Later she told me she changed her mind and won't go."

Sajid believes he convinced "a lot" of people to turn away from IS, but he grew tired of being a "fake supporter" particularly as more and more IS accounts were suspended by Twitter. He eventually closed his accounts.

Several months on, the battles fought by and against IS have taken their toll on his six closest contacts.

Three were now dead in Syria or Iraq, he said, two had been charged with terrorist offences, one in the UK, one in the US, while the last was alive and free and had now dropped his support for IS.

One person who has not, though, is his brother, who remains in Syria and continues to support IS.

Sajid said he had tried to convince him otherwise - but every time he challenged Arshad, he just blocked him.

Scared of losing what little contact he has with his brother, Sajid has given up trying.

Names have been changed in this article in the interests of guarding individuals' safety.