Undercover policing inquiry: Why it matters

- Published

- comments

The allegations of wrongdoing by undercover police officers that have emerged since 2011 have been extraordinary.

That steady stream of stories has led to the launch of a major public inquiry into their activities.

The breadth and nature of what is being alleged is almost too big to grasp, but it fundamentally comes down to a simple question of whether elements of the police were out of control.

So, here are seven key themes and allegations that lie in the road ahead - and some of the real practical and legal problems the inquiry faces.

1. The undercover relationships

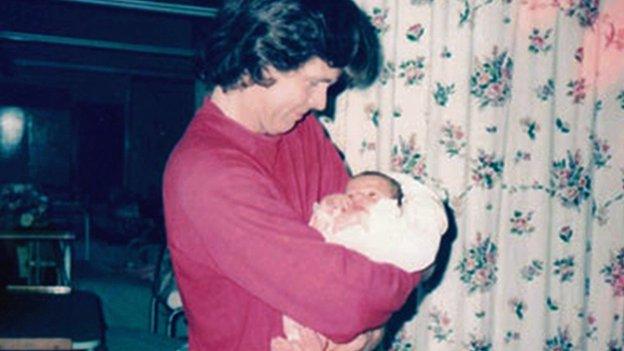

Some police officers had relationships with women whom they met within the protest movements they had been deployed to infiltrate. Last year, the Metropolitan Police paid one woman who had a child with an officer £425,000 in compensation.

Jacqui: "He watched me give birth... I shared that with a ghost"

There are approximately a dozen civil claims for damages before the courts amid allegations that officers were expected to have relationships as part of their cover identity.

But how many did so and under what circumstances? This is a huge challenge for the inquiry.

How will it find out and inform the public if the undercover officer involved remains unknown, there are no records and, crucially, the partner never had any suspicions?

2. The use of dead children's names

During the 40-year history of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) - the police unit at the heart of many of the allegations - officers used 106 "covert identities". According to a published police review, some 42 of them were almost certainly taken from children who had died - and the parents did not know about it. In 2013, a senior officer said the practice wasn't sanctioned by Scotland Yard - yet it seemed to have gone on for years.

How many names were used? Who authorised it? Should the parents have known?

If the names of the dead children are revealed, will that identify the officers the police want to protect?

Undercover officer Mark Kennedy infiltrated campaign groups

3. Miscarriages of justice

The undercover affair has so far led to more than 50 convictions being quashed after a failure to disclose that officers had infiltrated protest groups later accused of criminality.

The two largest cases relate to environmental protests at power stations, both of which involved Mark Kennedy, an officer with the National Public Order Intelligence Unit. He would drive protesters around, effectively facilitating demonstrations later found to have broken the law.

A review for the Home Office said there could be a possible further 83 miscarriages of justice - although its author, Mark Ellison QC, couldn't be sure there were not more.

So will the inquiry look at allegations that officers lied in court?

John Jordan was convicted over his role in a protest in 1996 - but was cleared on appeal in 2013 after it emerged that his co-defendant was Jim Boyling, an undercover officer. The officer even gave evidence in character. Jordan has been taking legal action for a full explanation of what happened.

4. Monitoring of MPs and trade unions

Peter Francis, the only former SDS officer speaking publicly, says that Scotland Yard kept intelligence files on MPs during the 1990s. During his time in Special Branch, he says he saw files on 10 Labour MPs which he and others would regularly update.

So what did that monitoring amount to? Was the information on MPs incidental, gathered as part of watching campaign groups? Or did some Scotland Yard chiefs want deeper intelligence on the MPs?

Separate allegations have emerged that undercover officers also gathered information on some trade union activists.

5. Stephen Lawrence campaign

The most toxic allegation so far has been that Scotland Yard had a "spy" in the Lawrence family camp. He later had a meeting with a senior officer helping to prepare Scotland Yard for the public inquiry into the London teenager's murder.

The exact nature of what information was gathered, why it was gathered and how it was used remains unclear.

The then Metropolitan Police Commissioner and now peer, Lord Condon, has said that had he known of the existence of such undercover action in relation to the Lawrences, he would have stopped it.

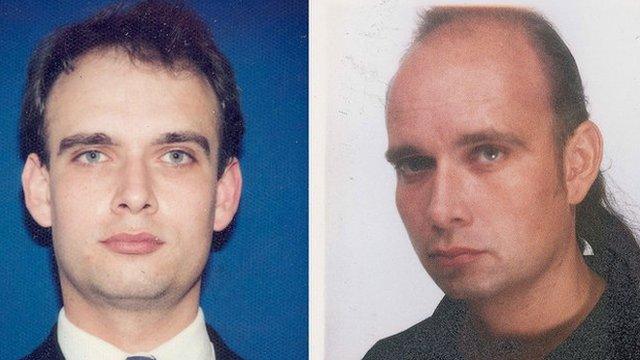

Peter Francis: transformed his appearance as he went deep undercover

6. The effect on the officers themselves

Peter Francis spent four years deep undercover and he eventually became mentally ill, suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. Today, he says some of what he was asked to do was wrong - and he wants senior officers to account for the way they deployed officers like him. He is not the only officer to have had concerns about the ethics of their work.

Phase two of the inquiry is expected to look at the "operational governance and oversight" of undercover operations, including how officers are selected, trained, managed and cared for.

7. NCND and anonymity

The most important acronym in this inquiry stands for Neither Confirm Nor Deny. It's a legal position adopted by the police and other security agencies in cases involving protection of undercover officers or sensitive sources. The first potential legal battle will come if police will refuse to admit whether or not they had officers deployed in specific circumstances.

Official reports have already revealed the existence of some of these undercover officers - such as the one who was in a campaign group close to the Lawrence family - but they remain anonymous.

If officers remain in the shadows because, quite simply, they were incredibly good at their job, police chiefs will almost certainly argue that the public interest lies in protecting their anonymity because of their legal duty of care.

- Published24 October 2014

- Published25 March 2015