Should there be more 'honesty' in sentencing?

- Published

- comments

'Earned release' for prisoners was first proposed in 2008

Michael Gove's first major speech on prison since he was appointed justice secretary contained a catchy phrase: Earned release.

It's a clever term that has a twin appeal - to law and order hardliners and the penal reform lobby.

It expresses the notion that release from jail is not automatic - the hardliners like that bit. At the same time, it suggests that earning release will involve prisoners bettering themselves by doing something constructive, which is what penal reformers want to see.

But however attractive Mr Gove's (far from fully-formed) idea may be, it's not new.

"Earned release" was first put forward in a Conservative Party policy paper in 2008, "Prisons with a Purpose, external", which includes several other proposals the new justice secretary is now considering, seven years on.

The principle of "earned release" was part of a section headed "Honesty in Sentencing". It claimed there was a "prevailing sense of injustice" when the public discovered that a criminal served a much shorter period in custody than the sentence handed down in court.

And, in spite of a number of changes to sentencing practice in the intervening years, it remains the case that almost all offenders spend less time behind bars than the sentence which is publicly read out.

More punitive

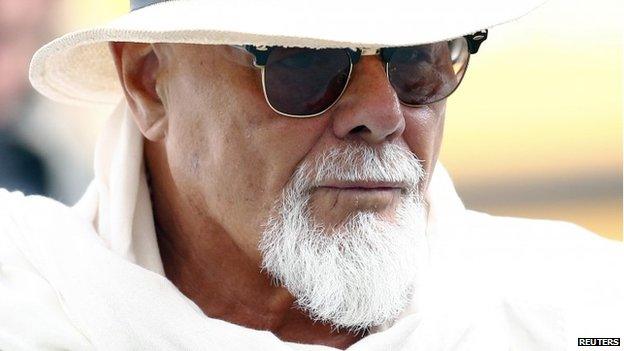

Take the case of Gary Glitter, the former pop star whose real name is Paul Gadd.

In February, Glitter was sentenced for an attempted rape, four counts of indecent assault and one offence of having sex with a girl under the age of 13.

In determining the sentence, the trial judge, Alistair McCreath, had a complex process to follow in which he had to consider the more punitive regime which exists now, together with the shorter maximum jail terms available when the crimes were committed.

"The total sentence is, therefore, one of 16 years' imprisonment," the judge declared.

Gary Glitter was jailed for 16 years, but is likely to serve only eight

The headlines duly followed. "Gary Glitter jailed for 16 years," said BBC News, Sky News, the Guardian, the Telegraph and numerous others. The Daily Mail predicted, external that Glitter, who's 71, would die in prison.

But the headlines, which took their cue from the publicly declared sentence, weren't correct.

Glitter will be freed at the halfway point of his sentence, therefore spending eight years in prison, not 16.

Only if his behaviour in jail is so bad that he's given added days to his sentence as a disciplinary measure will he be detained beyond halfway.

Once let out, he'll be subject to supervision and will have to abide by certain conditions for eight years; he could be sent back to prison if he re-offends or breaches those conditions.

But the plain fact is that this was really an eight-year jail term, not one of 16 years.

'Extended sentences'

The Conservatives' 2008 paper called for an end to automatic halfway-stage release and a new system of "min-max" sentences in England and Wales, with judges setting a minimum and maximum period to be spent in jail.

An offender's freedom would be conditional on them meeting requirements laid down by the judge, hence the "earned release" phrase.

The policy paper said there'd be another benefit as well: "It will lead to clearer sentencing."

Since then, new "extended sentences" have been introduced for some sexual and violent offenders who are assessed as posing a "significant risk to the public".

Prisons would not have the spare capacity to deal with longer sentences

It's a variation on the "min-max" idea, with no automatic release at the halfway point.

But most prisoners do not qualify for extended sentences and, says Sir Edward Garnier, one of the two MPs who wrote the 2008 document, the need for clarity remains as pressing as it was then.

According to the former solicitor general, people feel "disappointed" when they learn that an offender has been released earlier than they expected.

"It misleads the public," says Sir Edward. "That's where the lack of honesty comes."

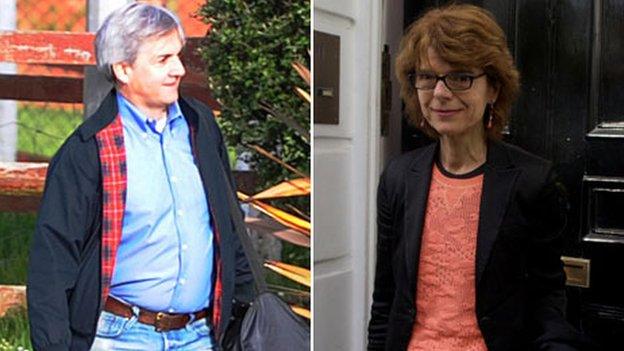

Huhne and Pryce

In some cases, prisoners serve even less than half their sentence. Those who receive terms of between three months and four years are eligible to be let out up to 135 days (about four months) before the halfway point as long as they wear an electronic tag and stay at home at specified times.

The scheme, Home Detention Curfew (HDC), external, which operates at the discretion of prison governors, isn't available for those convicted of certain violent and sexual offences.

But its widespread use since 1999 (more than 2,000 prisoners are currently on HDC) means the prison sentence served bears virtually no resemblance to that imposed in court.

There are similar arrangements in Scotland and a conditional early release scheme has just been announced in Northern Ireland.

Chris Huhne and Vicky Pryce spent only two months in prison, having been sentenced to eight

Among the more notorious HDC cases were those of Chris Huhne, the former Liberal Democrat cabinet minister, and his ex-wife, the economist Vicky Pryce, both convicted over a speeding points scandal. The pair were released after two months in jail, having been sentenced to eight.

Frances Crook, director of the Howard League for Penal Reform, agrees that greater clarity in sentencing is required to restore confidence in the process.

But she's concerned that any move to a system whereby the sentence expressed in court becomes the sentence served, or a "min-max"' arrangement, would lead to longer spells in custody.

"We'd have sentence inflation," she argues, because judges wouldn't want to appear soft. With more time in custody, there'd be less opportunity for offenders to adjust to life in the community.

"It means people wouldn't get support on release," Ms Crook adds.

Media role?

Although Mr Gove has yet to outline his thinking on sentencing there's no spare capacity in prisons to make a change that risks increasing sentence lengths and the prison population.

The Treasury is unlikely to stump up the money either for a department that is not shielded from budget cuts. So, could the media play a role in being clearer about sentences?

Mr Gove has yet to make clear his thinking on sentencing

Whenever an offender is sent to prison, reports focus on the headline jail term, as the Glitter case illustrates.

Does "life" mean life?

When a murderer is given a "life sentence", we often write that they've been "jailed for life", knowing that's rarely the case.

Out of 12,200 offenders serving life or indeterminate sentences, only 57 people have been sentenced for their whole life.

The vast majority are usually released at, or sometime after, they've served a "minimum term", which is announced in court.

Minimum terms in murder cases are generally between 15 and 40 years.

Bob Satchwell, executive director of the Society of Editors, acknowledges that some coverage is misleading, but says it's unfair to blame the press.

"All the media are doing is reporting what the law says," he explains. The overall sentence, even if only part of it is spent in custody, is the judge's "comment on the seriousness of the offence".

Besides, says Mr Satchwell, sentencing is a complex business that can't be encapsulated in a headline. "I think most of the public do understand that people don't serve most of their sentence."

Perhaps he's right: We've learned over the years that sentence imposed does not equal sentence served.

But at a time when trust and confidence in the criminal justice system is increasingly being questioned, surely there's a responsibility on everyone to be as clear and honest as possible.

- Published5 February 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published13 June 2014

- Published19 August 2014

- Published2 January 2014