Islamic State: The UK's gap between rhetoric and reality

- Published

David Cameron says the battle against IS is "the fight of our generation"

The rhetoric is certainly getting tougher.

David Cameron has recently labelled the group known as Islamic State (IS) as "one of the biggest threats our world has faced".

He's described the extremists as a "death cult" and the need to confront them as the "fight of our generation".

In a recent speech, the Defence Secretary, Michael Fallon, called it "the new Battle of Britain" against "a fascist enemy".

That's the rhetoric. Now the reality.

In 1940, in the real Battle of Britain, the RAF had hundreds of aircraft to defend the nation from a potential Nazi invasion.

Against IS, the RAF has been relying on eight Tornado jets flying from Cyprus.

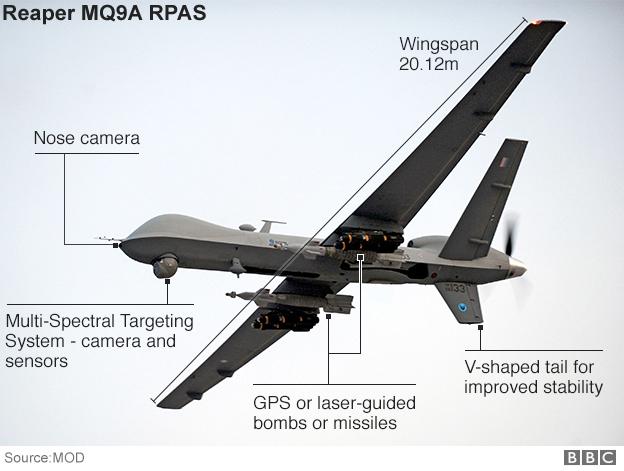

It has also been using 10 Reaper unmanned aircraft or drones to carry out surveillance and air strike missions.

Together the Reapers and Tornados have flown more than 1,100 combat missions over Iraq and carried out more than 250 air strikes.

In total the US-led coalition has conducted nearly 8,000 air attacks.

'Incoherent' strategy

So while Mr Fallon is keen to point out that the UK is the second largest national contributor to the military campaign, it's still dwarfed by the US effort.

In the words of the former chairman of the House of Commons Defence Select Committee, Rory Stewart, the UK's contribution is "modest" at best.

His successor, the Conservative MP Julian Lewis, has been more critical.

The RAF has been using eight Tornados based in Cyprus to attack IS

He has described the UK strategy against IS as "incoherent".

Mr Lewis has accused the prime minister of making policy "on the hoof" and made clear the government will need a proper strategy if it expects his backing to expand the air strikes to Syria. So is he right?

If the UK strategy is incoherent, then so is that of the US. After all, the British contribution is just a reflection of what America is and isn't doing.

Reaper drones:

First used by the RAF unarmed in October 2007, then armed the following year

Used for surveillance and air strikes, armed with Hellfire missiles and laser-guided bombs

They can fly at 290 mph with a maximum height of 50,000 ft

Controlled via a satellite link by a team of pilots from 13 Squadron at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire.

Both countries are prisoners of their past - their largely unsuccessful previous interventions in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

The over-riding strategy appears to be not to get dragged into another long war in the Middle East. So that means a limit to "boots on the ground".

The US has about 3,000 trainers in Iraq. The UK has a total of 135 in the north helping the Kurdish Peshmerga forces.

An 'infidel' enemy

The former Chief of the Defence Staff, Lord Richards, recently argued that the West needed "tens of thousands" of trainers on the ground if it wanted to make a difference.

Like Mr Lewis, he thinks the current strategy isn't working. Earlier this month he told the BBC that the West's efforts against IS were "woefully insufficient".

While it is still possible that the US and the UK could increase the presence of military trainers, the chances of either of them putting combat "boots on the ground" are slim to non-existent.

Many argue it would play into the hands of the extremists who would be bolstered in fighting an "infidel" enemy.

The UK has 135 trainers in northern Iraq working with Kurdish forces

That leaves it largely to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's army, Syrian rebels and Kurdish forces to do the fighting on the ground.

The West has made clear it won't help the Syrian regime while Mr Assad remains in power.

Training "moderate" Syrian rebels is not going according to plan.

The US Defence Secretary, Ash Carter, has admitted that so far America has trained just 60 Syrian fighters.

Turkey joins fight

As for relying on the Kurds, that's just become more complicated.

Turkey may have finally joined the fight against IS. But it appears to be more enthusiastic in targeting its old enemy, the Kurdish separatist group, the PKK.

The PKK have been allies to both the Iraqi and Syrian Kurds. Turkey's actions might end up weakening one of the more effective fighting forces.

So what more might the UK do next?

The government is now contemplating widening its air strikes to include targets in Syria, subject to parliamentary approval.

Combat troops are unlikely to replace Reaper drones in the fight against IS

The RAF is already carrying out surveillance missions over Syria and could easily switch to strike missions if and when the order comes.

But it would probably still be with the same limited number of aircraft.

At the end of the Cold War, the RAF had more than 30 front-line squadrons; today it has just seven.

Speaking last month, the Chief of the Defence Staff, Gen Sir Nick Houghton, warned that the RAF was already "at the very limits" of its fast jet availability, with the ageing Tornados mounting daily strike missions in Iraq and the more modern Typhoons regularly called upon to intercept Russian warplanes near UK airspace and in the Baltics.

Absent from the fight

As it did with Libya, the RAF could send some Typhoons to back up the Tornados at Akrotiri in Cyprus, but the Typhoon still has a limited ground attack capability.

It's also important to note that most US and UK warplanes have been returning to base from their missions without firing their weapons.

Air power may have limited IS's ability to move, but you still need an effective army to secure and hold the ground. And at the moment that army is absent from the fight.

Lord Richards recently told the BBC: "If you want to get rid of them [IS] we need to effectively get on a war footing."

While the government's words suggest that is now the case, its actions do not.

- Published4 August 2015

- Published27 July 2015

- Published19 July 2015

- Published20 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015