Cameron's first 100 days under scrutiny

- Published

The time to judge the achievements of this government will be about 1,800 days in, on the eve of the next election.

But with the first majority Tory government in almost two decades going at break-neck speed, as Labour does some soul-searching, the prime minister is keen to make much of the first 100 days.

It's an American import to British politics, although it's been around a long time.

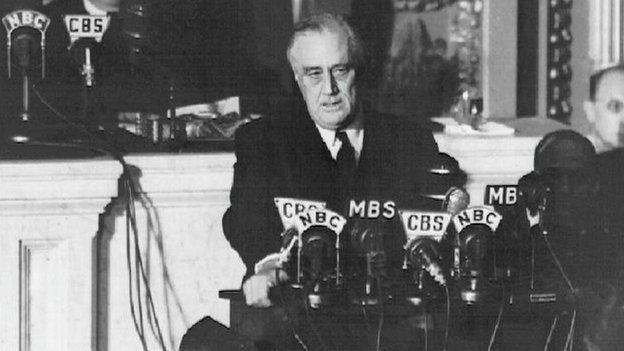

President Franklin D Roosevelt first spoke of the period back in the 1930s, when an administration was apparently at its most powerful.

David Cameron has focused on the most important and most problematic things in his first 100 days, and he's done it with no time to spare.

The first cabinet meeting of the new Tory government was held in Downing Street on May 12

The government has also pushed on with some unexpected measures.

Everything mentioned in the Queen's Speech is now going through Parliament. There was that extra summer budget which identified the extra £12bn in welfare savings.

There's been a whirlwind tour of various European capitals as the European referendum bill goes through the Commons.

The immigration bill, with its heavily trailed "crackdowns", is coming very soon. All of it designed to show what matters most to this government, and all at a pace that's meant to convey an urgency.

Some things have fallen by the wayside - the much heralded British bill of rights didn't make it to the Queen's Speech, moves to have a free vote for MPs on fox hunting were rejected, plans to introduce "English votes for English laws" have been delayed.

The deal on the future finance of the BBC was done quickly but the commitment to increase the licence fee in line with inflation is now "under review".

Franklin Roosevelt was the first to talk of a government's 100 day milestone

FDR's modern successors place more stock in the 100 days assessment because they have mid-term election campaigns to deal with after the first year, and often a presidential re-election campaign themselves after that to worry about.

David Cameron has neither, so he has more time to get things done. But on the other hand, not dissimilar to the person in the White House, he may have problems enforcing his will over the legislature because - remember - his working majority is in the teens.

Perhaps he doesn't have too much time, given the EU referendum will come by the end of 2017 at the latest.

That campaign will, at times, dominate the domestic agenda.

Don't forget Labour - they won't be looking inwards forever. And, of course, this is the beginning of the end for the prime minister, assuming he lives up to the promise not to serve a third term.

So he's getting a move on.

- Published27 May 2015

- Published21 July 2015

- Published30 December 2020