Drawings reveal Germans' World War Two boobytrap bombs

- Published

Laurence Fish was recruited by MI5 to design hidden booby trap bombs during the war

Drawings of wartime boobytrap bombs, including an exploding chocolate bar and devices intended to sink ships, have been rediscovered after 70 years.

The drawings were made by a young artist called Laurence Fish for MI5's counter-sabotage unit.

There is an incendiary bomb designed as a Thermos flask, an army mess tin with a bomb hidden beneath the bangers and mash, and a high-explosive device concealed in a can of motor oil.

There is a magnetic limpet mine for a ship's hull which explodes when detached.

And there are timing devices ranging from the highly complex to the remarkably simple - like a test tube full of dried peas which expand as they absorb water and push two contacts together.

All were unpleasant weapons dreamt up by German sabotage experts to spread havoc among their British enemies.

The exploding chocolate bar, it is rumoured, was intended as part of an assassination attempt on Winston Churchill - though how it was supposed to reach him, and how the Germans might ensure that it was Churchill himself who tried to break off a slab, rather than a member of his family or his staff, isn't clear.

One of Fish's drawings shows an Army mess tin adapted for nefarious purposes

The 25 drawings, exquisite examples of 1940s draughtsmanship, were commissioned from Laurence Fish by Victor Rothschild.

Rothschild and his secretary (later his wife) made up two-thirds of MI5's tiny counter-sabotage unit.

The third member was a seconded police detective inspector, Donald Fish.

When Rothschild was looking for someone to document the disguised and booby-trapped devices he was uncovering, Fish suggested his son, a self-taught draughstman who had learnt his trade before the war working for Alvis cars.

'Ingenious'

The idea was that the drawings would serve as a kind of manual for anyone who had to defuse similar devices. And there were plenty of them.

The historian Nigel West, who has written several books on espionage, says: "The Germans during the Second World War were very keen on destroying ships and their cargoes leaving neutral ports for the United Kingdom.

"The idea was to starve Britain into submission. And they created some very ingenious devices which could be smuggled aboard ships and placed in the cargo holds with long-term timers: they wanted the ships to catch fire or to sink whilst out at sea."

Another of the boobytrap devices documented was a motor oil can with an explosive inside

Rothschild was a larger-than-life character, a scientist and self-appointed expert on many things, who as the fourth Baron Rothschild later became head of Prime Minister Edward Heath's pioneering Think Tank.

He was also brave. He won the George Medal for defusing a booby-trap device concealed by the Germans in a consignment of onions which had come by ship from Spain via Gibraltar.

A Royal Navy lieutenant had lost an arm and an eye tackling a similar device.

Rothschild gave a running commentary over a field telephone as he worked, so that his secretary could take notes and keep a record of every step he took, in case something else went wrong.

'Amazing' partnership

"Rothschild was immensely generous with his family's money," says Nigel West.

"He didn't draw a salary; he almost certainly paid Fish for the illustrations himself; he made his family house up at Tring available to MI5 officers who were bombed out of their houses in central London.

"And when MI5 needed an office in Paris upon the liberation, Victor just simply made available one of his mansions."

Rothschild, who was a lieutenant colonel, commissioned drawings from Laurence Fish, a humble aircraftsman, via letters stamped "Secret". They show evidence of a close working relationship.

"They got on so well together," says Fish's widow, Jean Bray.

"It was an amazing combination.

"Rothschild had very great respect for Laurence... I don't know why, but it worked well."

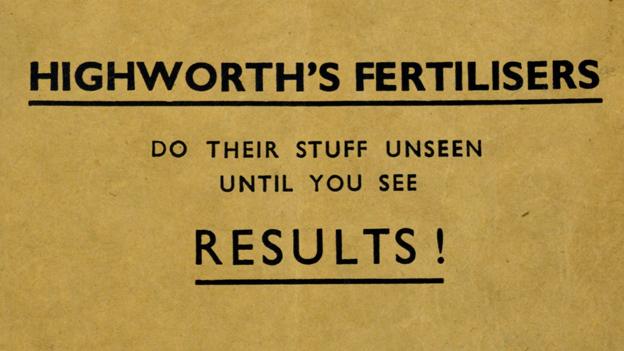

The Germans hoped to starve Britain into submission by destroying supply ships

Fish kept the letters. But the drawings vanished. Rothschild had his favourite framed and hung it on the wall of his study. A couple of others were known from photographs. Otherwise, nothing.

Then a few weeks ago, members of the Rothschild family were clearing out their house in Suffolk when they discovered a sheaf of drawings in "deep storage" in a chest of drawers.

Rothschild's daughter Victoria realised what they were and got in touch with Jean.

Rotating disc

In the 1950s and onwards Laurence became a successful poster artist, graphic designer and landscape painter, putting his wartime work behind him.

"It was interesting work obviously," Jean told me, "and it must have been very concentrated work, but he wasn't going to make any money out of it so as soon as the war was over he'd got to do something that earned him a penny."

In her husband's old studio at the top of their home in the pretty Gloucestershire village of Winchcombe she showed me the pile of drawings, carefully wrapped in brown paper, cardboard and tissue paper, that Victoria Rothschild Gray had sent her.

The exploding chocolate bar may be the most famous, but Jean's personal favourite is an exceptionally intricate 21-day timer involving a rotating disc.

At the top, it says, in especially bold letters, "Do not unscrew here." At the bottom, equally bold, are the words: "Unscrew here first."

Now Jean hopes that a museum or archive will agree to take the pictures: freehand precision drawings made long before the age of computer-aided design, and a fascinating record of fiendish wartime ingenuity

- Published29 September 2015

- Published24 October 2013

- Published7 February 2011