Why does Middlesbrough have the most asylum seekers?

- Published

No more than one in every 200 of the local population should be an asylum seeker, government guidance says. Middlesbrough is the only place in the UK that breaks that limit, with one in 186. Why is this?

"No-one is happy to leave the place where he or she grew up. You have your roots there, you have your relatives, your memories, your friends, you have absolutely everything there," says Hanis, an English teacher from Syria.

"But eventually you start to realise enough is enough and you can't stand it anymore. You will either be killed or be used to kill people, so you choose to leave."

He crossed the Channel three months ago, hidden in the back of a food truck - the end of a long journey via Turkey, the Greek island of Kos and mainland Europe.

The truck stopped somewhere in the Midlands. He climbed out, spent a few hours in detention and was sent by the Home Office to one of the UK's six Initial Accommodation centres in Wakefield.

Private companies then decide where in their region those asylum seekers should live, based mainly on the availability of cheap housing.

"They put me in a van with other asylum seekers, brought me to Middlesbrough and helped move me in," says Hanis. "It was very well-organised."

Find out more

Watch Jim Reed's film in full here, external

A dispersal system was put in place by the last Labour government to deal with what was then seen as a concentration of asylum seekers in south-east England.

In 2012, three private contractors - G4S, Serco and Clearel - won the contracts to run it under a Home Office scheme called Compass, who are paid to provide accommodation on a per night basis.

The idea was to reduce the overall bill for taxpayers and ease the burden on councils like Kent and Essex.

'Profit from misery'

But critics say it has simply shifted large pockets of asylum seekers north to a handful of towns and cities with cheap or unused accommodation.

Middlesbrough is one of these - there are entire streets of boarded-up houses gradually being turned into shared accommodation. The average terraced house here sold for £79,039 in September 2015, Land Registry figures show, less than half the UK average for houses of all types of £184,682.

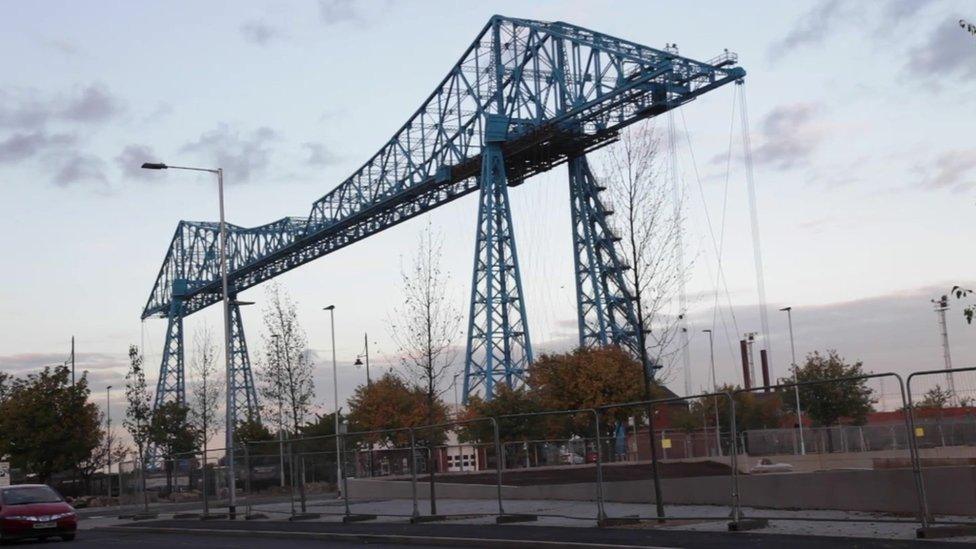

Middlesbrough is now taking in more asylum seekers

"The dispersal system is predicated on the availability of housing, I think that's the inappropriate way," says Andy MacDonald, Labour MP for Middlesbrough since 2012.

"To allow this to be a commercial exercise where profit is made out of people's misery is viscerally unacceptable. Other towns and cities are doing very little by comparison with a town like this."

Figures from June show:

Middlesbrough alone was housing 746 adult asylum seekers claiming the most common form of government support

The entire south-east region outside of London, covering eight counties plus the Isle of Wight, was accommodating only 494

185 of the 442 local authorities across the UK were not housing a single asylum seeker, while individual towns and cities were housing hundreds. Liverpool had 1,417, Rochdale 984 and Glasgow 2,602

Councillors in Middlesbrough and neighbouring Stockton say they are proud of the welcome that asylum seekers have been given by the public.

But anecdotally at least, it's not hard to find locals worried about the impact on public services. On a sunny afternoon in the town centre it's common to hear complaints that schools and GP surgeries are overcrowded.

Support

Refugees waiting for a decision on their asylum applications are not allowed to work. They collect a special card from the Post Office worth £36.95 a week to pay for food, clothing and toiletries.

In Middlesbrough an extra support system has grown up run by a network of local charities and religious organisations.

Asylum seekers attend a church-run session for English lessons

There is a dedicated GP service and a roster of activities from English lessons to keep fit - all staffed by local volunteers.

"It's just about giving a human welcome really," says Ailsa Adamson, the manager of the Methodist Asylum Project.

"The biggest thing on their minds when they arrive is how far has their asylum case progressed and when they are going to be interviewed.

"We try to show them where they need to go from the GP to the Post Office and other key buildings. When they first arrive it can be isolating."

Successful asylum seekers are given either indefinite or a five-year "limited" right to stay in the UK - they then have 28 days to move out of specialist housing and into local authority or private accommodation.

At that point some will move away from the area but many, especially those with children already in local schools, choose to stay.

Local accent

Heeba, from Somalia, has been given leave to remain with her three children. She says her biggest problem has been getting to grips with English and the local accent.

"I was talking to my friend in another city about the help refugees were getting. He tells me no-one helps him. I think Middlesbrough treats me very well," she says.

Hanis says: "Compared to the hell we are coming from this place is like heaven. There is no shelling. There is no problem with electricity, water, food. So it's not a shock when people arrive. It's a very good start."

A spokesman for G4S said it only placed people in communities "after close consultation and approval from the affected local authorities and the Home Office".

The Home Office said it would not normally go beyond the population ratio without the agreement of the relevant local authority.

"We work closely with local authorities to ensure that the impact of asylum dispersals is considered and acted upon — this includes closely monitoring existing arrangements and the impact on local services and community cohesion," a spokesman said.

Middlesbrough Council said it had not agreed to exceed the numbers.

The Victoria Derbyshire programme is broadcast on weekdays between 09:15 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News channel.

- Published28 January 2016

- Published20 September 2015

- Published4 September 2015

- Published4 March 2016