The children who hit their parents

- Published

What is it like to be bullied by your own child? Experts say a growing number of parents are experiencing violence at the hands of their children. But why does it happen, and can these families be helped?

Luke, 13, hits his mum if he does not get something he wants, or is grounded and wants to go out.

"I won't do it too powerful because if I hurt her and she has to go to the doctors' or hospital, she'll have to tell them what's happened. I don't do it as light as a feather, but hard enough to scare her," he says.

Luke - not his real name - threatens, spits, hits and throws things at his mum. "I just get angry," he explains. He cannot say where the anger has come from, but his mum says it started when he was seven.

Luke says he does not mean to hurt her and knows it is wrong afterwards. "I don't like it. I don't know. I love my mum," he explains.

Witness violence

Children who regularly attack their families do it for a variety of reasons, often due to a need to control the people around them.

Dr Peter Jacobs, a clinical psychologist who works with affected families, says many cases involve homes where violence regularly takes place - which means the children become used to it.

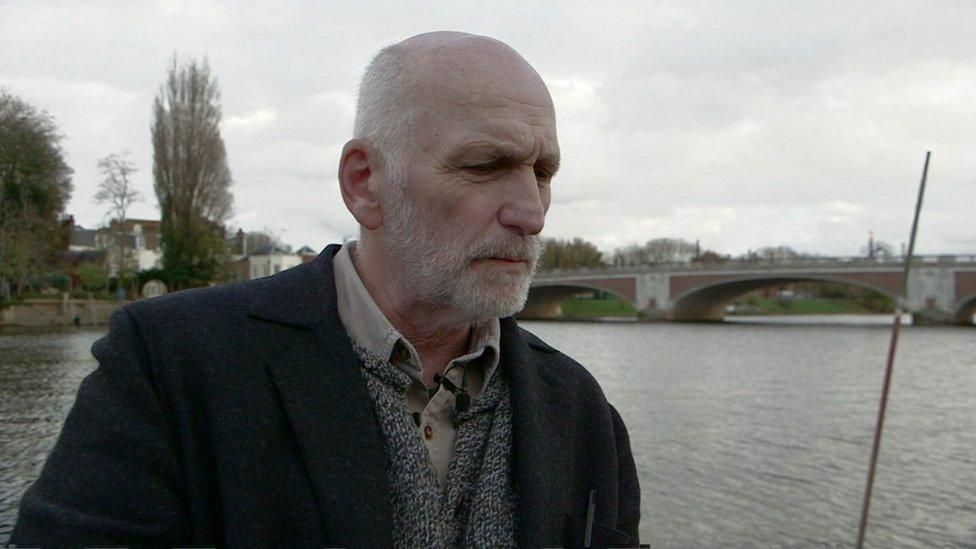

Dr Peter Jacobs helps families who have aggressive children

"It becomes normal. Young people, as anyone, take their cue to behave from their social environment.

"So when the people around them seem to take it for granted that violence or abusive behaviour happens - then they will feel encouraged to continue in that manner," he explains.

It is often also the case that the traditional form of parental authority has been eroded. If they become used to a child's pattern of violent behaviour, their presence in the child's life becomes diminished.

Dr Jacobs says: "So you will have parents who will avoid their children, or walk on eggshells.

"You will have parents, or even foster carers, who will try to avoid doing things that will trigger off their children. But that means very often they will start giving in to their children's demands.

"More and more they find themselves being wrapped around their children and that reinforces the controlling behaviour."

Under-reported

In the last year, 2,549 14 to 17-year-olds were prosecuted for a range of domestic abuse offences on family members and in-laws, figures from the Crown Prosecution Service show. This is compared with 2,114 in 2013-14.

The youngest defendants were aged 10 to 13 and of those, a total of 111 were convicted.

West Midlands Police say they have dealt with almost 200 cases of under-18s abusing their parents in the past 12 months, but only 13 were charged.

DCI Sally Simpson, domestic abuse lead at the force, says around six in 10 allegations are dropped because the victim decides not to support a formal prosecution - most are reluctant to criminalise their own children and will exhaust other options first.

"I don't think there's any doubt it's an under-reported offence and I suspect the actual figure is much higher," she says.

'Sarah' needed seven stitches after her hand was cut in a struggle with her son

One person who involved the police was "Sarah", whose teenage son began attacking her two years ago. Initially, he pushed and shoved her, but then he used a cricket bat.

"I didn't actually think he was going to do it, I just stood there and let him because I thought 'no, my son's going to come to his senses, he's not going to do this to me'," she says.

Things came to a head when she took his phone away and he threatened her with a bread knife. In the ensuring struggle she was badly cut and needed seven stitches.

"There was just almighty fear, almost like you're faced with a criminal in your home. Then my hand was cut - that was the point at which I had to admit I had this violent child," she says.

Sarah's son was arrested and given a 12-month referral order. He is currently living in a home for young people whose circumstances present a challenge for social services.

She says dealing with the authorities was an exhausting and upsetting experience and she felt there was no-one to help her.

'Calmer now'

Meanwhile, Luke is on his fifth week of a pioneering programme which rehabilitates relationships between teens and their parents. So far five families have completed it, with a further six families due to finish soon.

Cherryl Henry-Leach, who runs the nine-week course in Doncaster, says abuse by teenagers poses a significant challenge and parents can feel shame while living in crippling fear.

Many teenagers on the programme have witnessed domestic violence between parents, she says, so the project attempts to "denormalise" abuse and help them move on to healthier relationships.

"Each case in its own right is quite heartbreaking. For me, these families are fractured and need support to get back on track and move forward together in a healthier manner," she explains.

The programme also looks at the impact such violence can have on other members of the family. "Siblings have the opportunity to work directly with us as well," she adds.

Luke says the project is helping him with his anger: "I used to hit my mum at least twice a week and I haven't hit her in three, four weeks, and that's an improvement.

"I'm calmer now. I'm not so angry. I'm getting closer to my mum. I don't want to be a bad person."

The minister for preventing abuse and exploitation, Karen Bradley, said: "We recognise that adolescent to parent violence and abuse (APVA) is a hidden form of domestic abuse that is often not spoken about.

"That is why earlier this year the Home Office published information for practitioners working with children and families on how to identify and address the risks posed by adolescent to parent violence and abuse.

"The guidance aims to raise awareness of this issue, provide protection to victims and ensure an appropriate safeguarding approach is applied."

The Victoria Derbyshire programme is broadcast on weekdays between 09:15 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News channel.

- Published28 October 2015