What's happening to police numbers?

- Published

The terrorist attacks in Paris have focused attention on the preparedness of British police and security services to deal with similar threats.

Senior officers, including a former Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, external, have warned that anticipated budget cuts put at risk the ability of police to respond with the speed and the scale that would be required in such circumstances.

So, what has been happening to policing numbers and budgets in recent years?

What has the relationship between the police and politicians been like?

For much of the 1990s and the first decade of this century, both main political parties were engaged in something of a charm offensive with the police service. Law and order was high on the political agenda, with the consequence that keeping the police onside was expedient.

The election of a Conservative-led coalition government in 2010 changed the landscape and the period since has seen a much less comfortable relationship between the government and the police service.

The home secretary for the whole of the period since 2010, Theresa May, has been vocal in her criticism of many aspects of policing - including historic cases like the 1989 Hillsborough disaster and the abuses of undercover policing, to the day-to-day problems stemming from the misuse of stop-and-search powers.

Arguably, however, it has been the imposition of drastic budget cuts, with more promised, that has exercised senior officers the most.

What has happened to police budgets?

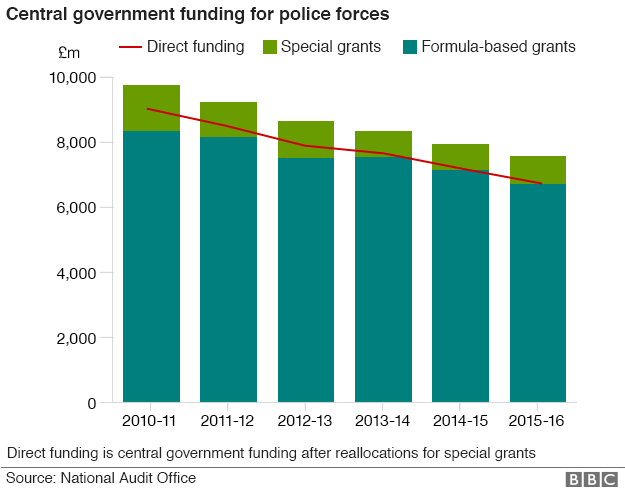

During the five years of the coalition government, the central government contribution to police expenditure was cut by one quarter in real terms. Although this was slightly offset by local increases in council tax, it still resulted in an overall 18% reduction in police budgets in real terms.

To cope with budget cuts, police forces have started to make a wide variety of changes to the ways in which they work. There is now greater collaboration between forces and greater use of shared services while many forces have reduced costs by closing police stations, reducing procurement costs and reorganising the workforce.

Most significant of all though are the reductions to the workforce. But how significant has that actually been?

How has the police workforce changed?

In the five years from March 2010, police officer numbers declined by close to 12% - a loss of almost 17,000. The decline in the workforce was even greater, with a loss of 15,877 support staff and 4,587 police community support officers (PCSOs).

These are undeniably very significant cuts, but they do need to be placed in longer-term perspective. The very significant increases in both police budgets and numbers that took place under the previous Labour administrations mean that both officer and overall workforce numbers are now back roughly at the levels they were between 2001 and 2003.

How are forces coping? The home secretary's view is that this is a success story, with crime continuing to decline from its high point in the mid-1990s despite the budget cuts and workforce reductions.

But there are signs of strain. Although a recent inspection by the National Audit Office, external found fairly limited evidence of what it calls "workplace stress" - meaning most forces appear currently to be coping reasonably well - they did note signs that some forces were likely to find it difficult to manage in the medium term without major changes in the way they operate.

What does the future hold?

The chancellor's spending review, to be announced on Wednesday, is expected to confirm further huge reductions in the central government contribution to police expenditure - rumoured by some to be as high as 20%.

Again, some of this may be offset by increases in council tax, but the search will be on for how best to reduce expenditure. More collaboration, further use of the private sector and sales of police property will all be in the frame.

There will also be further very significant reductions to the workforce. One large metropolitan force, the West Midlands, has already announced plans to slash the number of PCSOs, and it is likely that many others will follow suit. Further substantial falls in both officer numbers and in civilian staff are inevitable.

Some of this may also make the police and others reflect with increased seriousness on the breadth of the police mandate. Is it necessary for the police to do everything they currently do? If not, who else might do these things and with what consequence?

Royal Commissions are unpopular, but this might be a time to take a step back and give such questions the serious thought they deserve.

Whatever else may change, the responsibility for dealing with the threat posed by international terrorism is and will remain a central part of the policing task. To what extent do budget cuts undermine this capability?

How equipped are the police to deal with major threats?

British police officers remain unusual in not being routinely armed. Firearms remain the domain of specialist officers but, as much else, this too has been an area of decline in recent years, the total having fallen by 15% between 2009-2014, external.

The Metropolitan Police - the force most likely to bear the brunt of any major terrorist threat - has a Specialist Firearms Command (SC&O19), with a carefully protected budget, but in the wake of the Paris attacks the Commissioner announced that the number of armed response vehicles had already been increased. And while the capital's armed capability had been reduced by one-fifth since 2008-09, he was looking for ways to reverse this trend.

But it is not just the armed police response that is crucial. As is true of all policing - counter-terrorism is no different - successful operations rely upon information flows from the public and intelligence gathering.

Here again, budget restrictions will almost certainly reduce, perhaps radically, the numbers of PCSOs on the streets - part of the public face of the service - and are likely to pose significant challenges to neighbourhood policing.

As things stand it is hard to assess the extent to which austerity has affected the police service's ability to meet the demands that seem likely to confront them. What is more certain is that this will likely be a source of political contention for some time to come.

Tim Newburn is Professor of Criminology and Social Policy at the London School of Economics, external. He also writes for The Conversation, external website.

Spending Review 2015 - 25 November

The Spending Review is a five-year projection of government spending. In effect, it decides how £4 trillion of taxpayers' money will be spent by setting caps on government departments. Deep spending cuts are expected as Chancellor George Osborne seeks to balance the books.

Explained: Which government departments will be affected?

Analysis: Latest from BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg

More: BBC News Spending Review special report

- Published22 November 2015

- Published24 November 2015

- Published20 November 2015

- Published20 November 2015