Can British forces make a difference in Syria?

- Published

Other countries have been bombing Syria for some time

The world has changed dramatically since August 2013 when the British government last tried to win parliamentary approval to conduct bombing operations in Syria.

Then it was a question of striking at President Assad's forces as punishment for his use of chemical weapons. In the event the government lost the vote and no bombing occurred.

Since then the Islamic State organisation has emerged, controlling what it describes as a caliphate, encompassing territory in both Iraq and Syria.

IS has also demonstrated its ability to carry out or inspire attacks against tourists in Tunisia, against a Russian airliner over Egypt, and against a variety of targets on the streets of Paris.

A broad coalition (including the UK) is carrying out air strikes against IS in Iraq and a smaller number of countries are hitting targets in Syria too. (RAF aircraft are conducting intelligence-gathering missions over Syria, but generally not releasing any weapons.)

David Cameron on IS: "They have already tried to attack us"

Mr Cameron went to the House of Commons on Thursday to set out the government's case for extending air strikes into Syria.

He clearly believes that this is the right thing to do, that Britain's participation wasn't just essential alongside its key allies, but that it would also make a difference to the campaign. And furthermore, he believes that a reinforced military effort would bolster diplomatic efforts to end the Syrian crisis and increase the chances of a comprehensive settlement.

Tornado capabilities

So, can British forces make a difference?

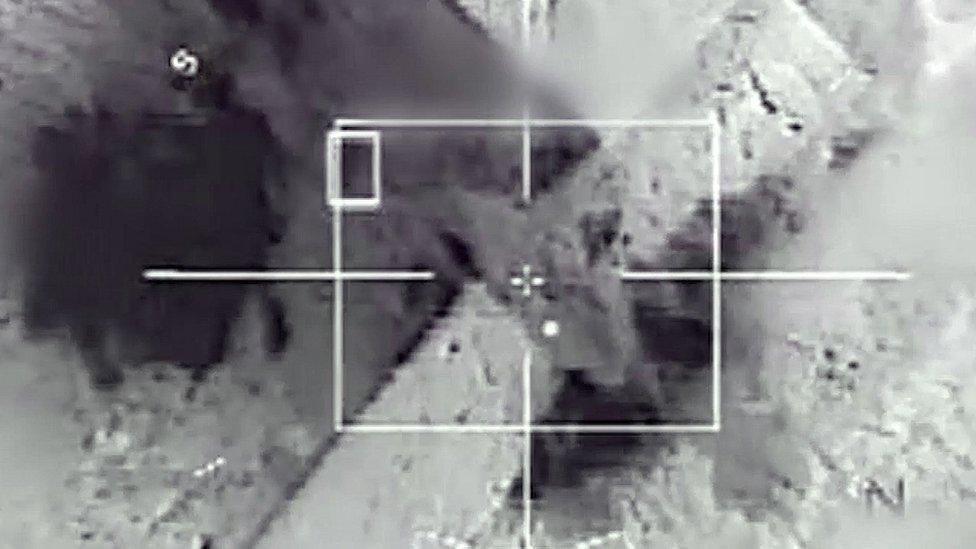

The PM argues that the particular capabilities of the RAF - the Raptor reconnaissance pods on its Tornado aircraft and their ability to deliver small but highly accurate Brimstone missiles - provide something that others don't have.

That, he says, is one of the reasons why Washington and Paris want the UK engaged. The RAF's equipment is well-suited to so-called dynamic targeting - i.e. where an aircraft overflies a selected area, locating targets for itself and then engaging them.

The PM argues that the RAF's Tornado aircraft gives the UK an added capability

This particular "niche" capability is one that even the Americans don't have and combined with the Raptor pod, which is responsible for some 60% of the tactical intelligence gained over Iraq, it is a useful additional tool to have in the airpower toolkit.

However, there are only eight RAF Tornados currently based in Cyprus.

While there is talk that if strike operations are extended to Syria, a small number of additional jets may be deployed, Britain's air contribution remains relatively small, though nonetheless significant.

With the arrival of the French carrier in the eastern Mediterranean, for example, France has more than three times the number of aircraft the UK has.

Mr Cameron also explicitly ruled out the deployment of British combat troops on the ground. Indeed he insisted that there were local ground "troops" - be it Kurdish or Sunni fighters - who were capable of retaking and holding territory from IS.

Let's look at some of the key elements of the prime minister's case.

IS represents a real and direct threat to the UK. This is about Britain's national security and the safety of British citizens. They had already been attacked abroad in Tunisia. IS, the PM said, had repeatedly tried to carry out attacks in the UK; several plots in the UK linked or inspired by IS have been disrupted.

Bombing in Syria would not change the threat equation in the UK. Britain, he insisted, was already under the highest level of possible threat from IS. The intelligence chiefs believe that Britain is in the top tier of potential IS targets.

This is all part of a comprehensive strategy. Mr Cameron was at pains to stress not only the need for military action but also its limits. It had an important part to play within a wider comprehensive approach that included diplomacy, humanitarian aid and, in the longer term, efforts to help the governments of Iraq and (one day) Syria to build up good governance.

France stepped up its air campaign in Syria and Iraq following the attacks in Paris

Mr Cameron made his arguments well and the government has released a lengthy written response to the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, whose earlier report raised many questions about the whole trajectory of the struggle against IS. It would be fair to say that many of those questions were heard again in the Commons today.

What would Britain's additional contribution to the effort in Syria really amount to? Were the available ground forces, especially in Syria, really capable of doing the job against IS?

Above all, is this much-vaunted comprehensive approach really worth its name? Syria is such a complex problem. How does the war against IS fit in with the struggle to remove President Assad and create a new inclusive government in Syria? Can one battle be disentangled from the other?

Mr Cameron acknowledges this complexity. But his case is that something needs to be done now and that British inaction also has consequences.

In the wake of the Paris attacks in particular, there is a sense that the mood in the Commons is changing. But has it changed enough to give Mr Cameron the clear backing that he needs?