Bowie death underlines power of the obituary

- Published

David Bowie's death has been marked across the world

Some sour souls will already be moaning about the tidal wave of tributes crashing all around us following David Bowie's death.

There is an "off" switch not just to life but to the radio and TV.

They can always stop reading, watching and listening, but they will still be missing the point.

It's not about him, it is about us.

Obituary has come a long way from those little black-edged notices in the staid newspapers.

Special programmes on the TV and radio are the modern equivalent of a state funeral, the media playing the previous role of government in judging the measure and importance of a life.

Who merits the full treatment is instinct not calculation, but one that tells us quite a lot about the world that has gone, the world that is now, and the way the departed has touched our own lives by negotiating a path between the two.

My teenage children, knowing I am a bit of a Bowie fan, after giving me a hug and saying: "Are you sad?" asked me: "Who would be like him for us?"

A puzzle remains after my trite: "No-one."

The real answer is we cannot yet tell.

Will Justin Beiber or Hozier grow alongside them, reflecting changing times?

Could it be Matt Smith or some YouTuber I've never heard of, who matches their world's measure over the next 40-odd years?

That we can't yet know is the point.

I claim no mystical prescience, but the night before Bowie's death was announced, I was listening to his latest and last record, Blackstar, and reflecting on his mortality and the way the lifeblood of his work has pumped through the veins of my own life.

Diana comparison

My odd night-time conclusion was that he was much like Princess Diana.

A generation of girls grew up looking towards a fairytale figure, all Disney and flowers and filigree hope, only to see, as they grew in to adolescence, the glass slipper shatter, the castle surrounded with thorns, Beauty's Prince Charming turning into a bit of a Beast.

But it wasn't just that she echoed their lives.

The attitude towards her relationship with the rest of the Royal Family said something about a desire to keep a system but shed the 1950s formality.

Were there parallels between David Bowie and Princess Diana?

The impromptu shrines weren't the import of Catholicism into a Protestant country but the loosening of Britain's emotional top button.

Now, flowers and candles are sad adornments by many a roadside, in public mourning of lesser known but just as loved victims of tragedy writ small.

The act of mourning changed one small aspect of mourning itself.

Similarly, the homages to Bowie reflect the depth of our change.

Most talk about how he helped alter our attitudes towards sexuality.

The very fact this is a commonplace observation, an unquestioned achievement on his part celebrated in the mainstream media, tells us much about our values.

He helped bring the demimonde, external into the living room, settled comfortably in an armchair next to Auntie Agnes.

Up to a point. No-one (thank goodness) is shouting: "He perverted our children!"

But when I first heard Bowie back in the early 1970s, the idea that gay marriage would one day be legal while drugs weren't would have sounded preposterous.

How we talk about him - not so much about the cocaine and the Nazi salute - is a measure of what has changed and what hasn't.

Political deaths

Few politicians have the emotional pulling power of a generation-spanning pop star, but their deaths too allow us to negotiate with the past.

Denis Healey's death at the end of the year, was more than the chance to reminisce about a very witty man with a razor-sharp intellect - it allowed a very timely examination of Labour's attitudes towards unilateralism, Nato and Europe.

Obituary can show us how little has changed as well as how much.

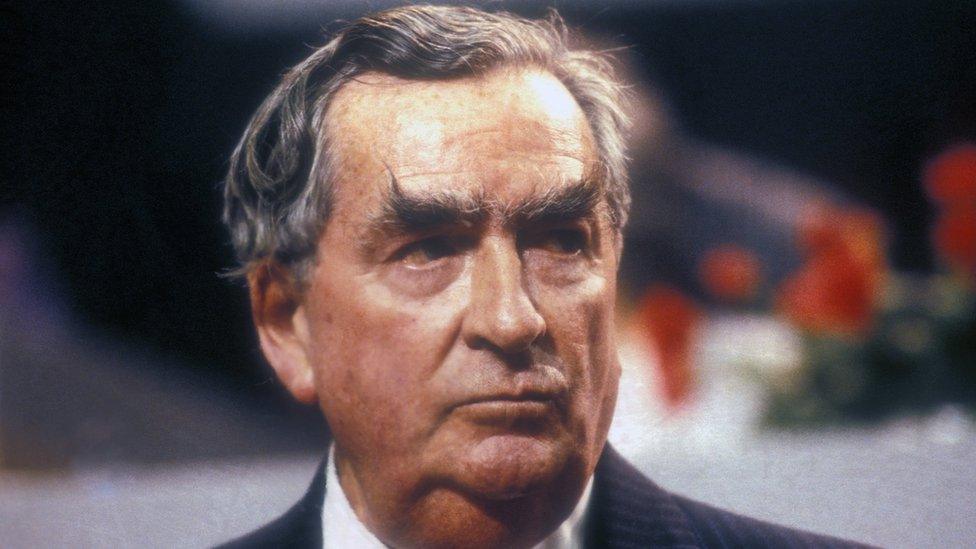

Denis Healey's death was time for reflection on Labour's evolution

Similarly, while the death of Lady Thatcher allowed some to make a sober and detached assessment of probably the most important British politician of the last century, it also reignited old bitterness, raked up Marmite emotions.

Perhaps it is too soon to evaluate some legacies, or perhaps there was a pivot point that deepened divisions so they still divide.

Deaths are a punctuation mark - some at the end of a sentence, others a paragraph, still others a chapter.

There will be a moment when our monarch changes.

Let us hope it is not soon, but come it will, and we will be left not only mourning but debating the passing an era longer than most of our lives.

Baroness Thatcher's funeral reignited strong feelings on both sides of the political debate

It will be a trigger for a momentous reflection on our nation's journey and destination.

The revolution may not be televised, but hereditary generational change will be.

Beware - the act of intense obituary can alter the future itself.

But there are some things we don't talk about much.

How and when someone dies affects the coverage.

Untimely death

An early, untimely death will always make more of an impact for obvious reasons - shock and surprise are part of what makes something newsworthy.

Going gently, slowly into the night, lessens the blow for the rest us.

I've heard quite a few news wire snaps greeted with: "I thought they died years ago."

Maybe the once-famous departed and their family would not be bothered at this late-found obscurity, but I suppose that depends on the nature of their twilight.

Bowie was not a youth, but his death was a shock.

We didn't know about his cancer and a year shorn from the Bible's allotted span seems these days a bit pinched.

An artist at the height of his powers, apparently happy in his personal life, has, we might feel been cheated, robbed of a deserved future. Maybe.

Napoleon and Shakespeare: dead at 52

He did better than Napoleon and Shakespeare, both dead at 52, both still very much alive in impact and imagination.

Will those who outlast him by several scores of years do better in the end?

These days, we expect more, indeed greedily grasp it, staying alive sometimes becoming more important than living a life.

We do not like, as a society, talking about death.

I do not like talking about it.

But perhaps we should, as more and more people expect to live longer, but maybe not better, lives.

There is no good time to go - as the joke goes, the only thing worse than getting old is the alternative.

After all the fuss about alcohol units a week, one witty letter writer in the Telegraph castigated those talking about "an increase risk of death".

He pointed out the risk of death was 100%.

We are faced with a barrage of weekly headlines on how to live longer.

There are fewer on how to make those extra years worthwhile - or the horrible fact that many of us will dwindle into a state as dazed and confused as the most addled addict, increasingly bound to bed or chair.

It should be a cause for great alarm and debate.

Timing is all, and Dear David, theatrical to the last, managed his exit for the maximum applause.

He bowed out singing, on the title track of his final album: ''Something happened on the day he died."

And maybe it did - to the very last he was plugged in to the future, mapping the zeitgeist.