Press turns both barrels on the Met Police

- Published

- comments

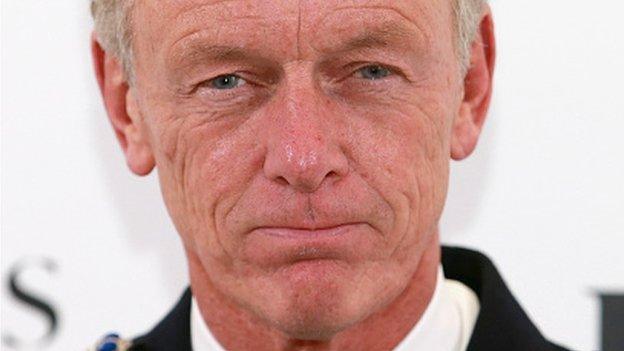

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe has attracted much criticism

Barely a day goes by without a newspaper headline condemning the Metropolitan Police or its Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe.

Last week, it was the Daily Mail's turn, external, in a reference to Operation Midland, the investigation into allegations involving members of the establishment, it said: "'Shambolic' VIP child sex abuse and murder inquiry to close".

In January, the Daily Telegraph weighed in, highlighting the controversy over the commissioner's £65,000 Range Rover, external: "Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe criticised for taking new luxury car amid police cuts row".

And last September, in one of a number of critical articles in the Times, the Thunderer column said, external: "The Met Police's record on big investigations is dreadful."

It should come as no surprise the press highlights police failings, blunders and unusually large items of spending - that is news.

Readers are not interested in police inquiries that tick along nicely, crimes solved without fuss and senior officers who never change their car.

But over the past year or two, I have found myself asking whether the media, myself included, are giving disproportionately negative coverage to Scotland Yard.

After all, the Met's record on crime, external, in keeping with other constabularies, has been largely positive.

Between 2000-01 and 2014-15, the total number of offences logged by the force plunged from 994,233 to 709,174, a reduction of 29%.

Murders fell from 171 to 93 - the lowest figure since the 1970s, though it has edged up in the past nine months.

Confidence in the UK's biggest police force increased to a record level in 2014.

And, despite a number of hugely controversial cases - Stephen Lawrence, undercover policing, Mark Duggan - independent inspectors have not pressed red warning lights on the Met's performance, as they have done with some other, far smaller, forces.

Incredibly hard task

In a city with a population of 8.6 million, and growing, where in some boroughs 100 different languages are spoken, and where the vast majority of police officers patrol the streets without guns, unlike New York or Paris, that is quite some achievement - even more so given the bruising budget cuts the Met has had to make since 2010.

"The Met represents all the problems the police have - on stilts," says the criminologist Roger Graef, an independent adviser to the force, who has made award-winning police documentaries.

"What they're trying to do is incredibly hard," he says, adding that over the past 20 to 30 years, Scotland Yard has slowly begun to change its culture to be more professional, less corrupt and less racist.

The Met successfully policed the emotional friendly match between England in France in the wake of the Paris attacks

The force has been praised, for instance over its investigation into the killing of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko, but there is undoubtedly a sense within its St James's Park headquarters that the media tend to gloss over its successes, such as:

the calm and professional way the force handled the England-France football match at Wembley, just after the gun and bomb attacks in Paris

oversight of London's New Year's Eve celebrations, when other cities cancelled theirs

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe's career:

1979: South Yorkshire Police

1997: Assistant Chief Constable, Merseyside

2001: Assistant Commissioner, Metropolitan Police

2004: Chief Constable of Merseyside

2009: HM Inspectorate of Constabulary

2011: Commissioner, Metropolitan Police

2013: Knighted in New Year Honours list for services to policing

Operation Midland

Instead, the force appears to be continually on the back foot - no more so than with Operation Midland.

The Met made a mistake by initially describing the allegations from its key witness, known as Nick, as "true".

It was unwise for police officers to make such a judgment at the start of an inquiry.

Indeed, Scotland Yard later acknowledged it may have given the false impression it was "pre-empting the outcome", external.

That slip, together with claims detectives have struggled to corroborate Nick's allegations and difficulties handling suspects with prominent positions in public life, has fuelled a stream of critical stories.

I remain cautious about forming a judgment on Operation Midland.

From my experience, we tend to know a lot less about ongoing investigations than we think we do.

Some of the press reports I've seen appear to have an ulterior motive - to damage fatally the reputation of Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe (more about that later).

Nevertheless, Operation Midland has - on the face of it - been at the centre of some debateable decisions, particularly with regard to Lord Bramall.

According to Fiona Hamilton, crime editor of the Times, there is "no question" Midland has "major flaws". She denies having any agenda, saying it is her job to expose failings in Scotland Yard's investigations.

"I don't think we give them an unfairly harsh time," she says.

"The Met has a huge amount of responsibility and power - an enormous amount of power. That goes hand in hand with a lot of scrutiny."

Scotland Yard's response to the criticism over Operation Midland has been to issue detailed explanations of its decision-making - there have been four such statements since September 2015.

Allegations against Lord Bramall were found to have no substance

It is a relatively new approach, similar to that deployed by the Crown Prosecution Service when a high-profile case results in no charges being brought.

Scotland Yard's latest missive, a 900-word statement about the Lord Bramall-strand of Operation Midland, arrived in an email, a kind of digital tablet of stone.

The Met believes it is the best way of getting complex messages across to the widest possible number of people, given the proliferation of TV channels, online news outlets and social media sites.

It is welcome to the extent it aids understanding, but it is rather impersonal: a "take it or leave it" strategy that does not encourage questioning.

In the past, it was common practice for a select group of journalists to be briefed on sensitive operations, enabling them to put events into context, develop contacts and build a deep knowledge of policing.

Poor media relations

Since the Leveson Inquiry exposed how inappropriate some relationships between press and police were, that has largely ended.

And although there is work behind the scenes to keep editors up to speed, particularly on security and counter-terrorism, the pursuit of News of the World, Sun and Mirror journalists over phone hacking and corruption claims, together with the revelation reporters' phone records were obtained by police investigating allegations former Cabinet Minister Andrew Mitchell called police "plebs" during a row in Downing Street, has only served to widen the gulf between newspapers and the Met.

Kelvin MacKenzie called Sir Bernard "the most reviled police officer in recent history"

"There's been a relationship breakdown," Hamilton says. "There's no-one on the Met side reaching out, expressing the context of the difficulty of historical abuse investigations, the challenge they face in the light of recent history of cover-ups."

What that appears to have contributed to is a lack of support in the mainstream press.

When a public institution seems to be in trouble - the BBC or the NHS - there are commentators, leader writers and columnists who ride to its rescue, but it is hard to find that backing with the Met.

Kelvin MacKenzie in the Sun, for example, wrote last week that Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe had become "the most reviled police officer in recent history".

Sir Bernard does not have the charm or charisma of Sir John (now Lord) Stevens, who received a favourable press when he led the Met.

Lord Stevens was a charismatic commissioner

The current commissioner is a straight-talking policeman who doesn't always appear to brook debate; he has had tough decisions to make after the lows of the Leveson report and the inquiries into sex abuse carried out by the late entertainer Jimmy Savile, some of which have angered the media and the establishment. But should he really be reviled?

This week, Sir Bernard, who is seeking to extend his five-year contract when it expires in September, is expected to set out his views on relations between the police and the media.

At times, tension between the two is inevitable, healthy even. There will always be harsh headlines and sniping from the sidelines. The Met polices London, where the media spotlight burns the fiercest.

But if there's to be a more mature and informed debate; coverage accurately reflecting the realities of 21st Century policing; and commentary that shows an understanding of the challenges of complex inquiries, then the commissioner and his force need to open up a little more - and take further, measured, steps to rebuild trust.

- Published11 January 2016

- Published14 January 2016