Jury out on worth of legal high controls

- Published

Six years ago this month, I reported from the Channel Islands on a disturbing new phenomenon.

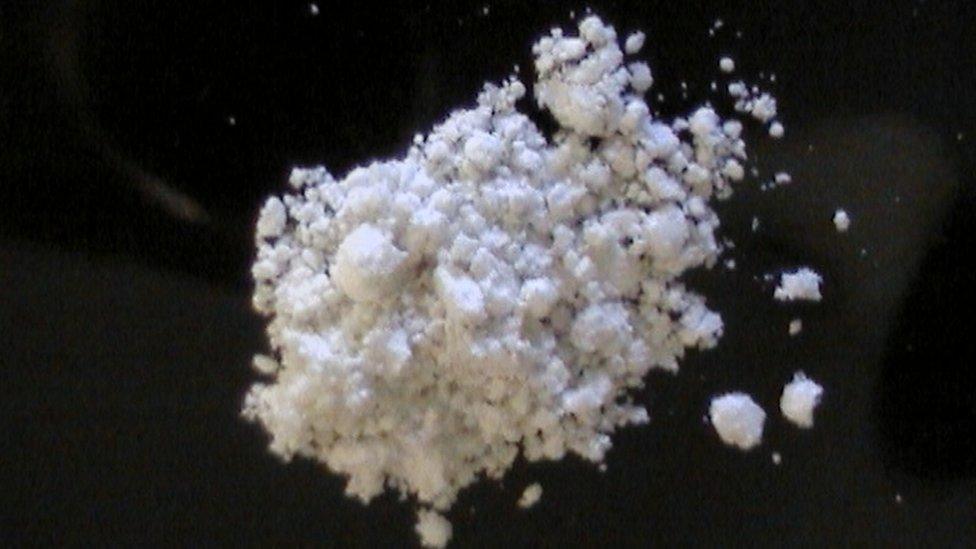

A drug called mephedrone was causing so many health problems its importation had been banned in Guernsey, while the Jersey authorities had criminalised its possession and supply, pre-empting the Home Office, which was still in the process of taking advice on whether the drug should be controlled in the UK under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act.

At Guernsey Prison, I was told more than a third of inmates were addicted to mephedrone, external, which was said to have a similar effect to amphetamines, ecstasy or cocaine and whose side effects included psychosis, weight loss and insomnia.

When the story appeared, some people questioned whether I had exaggerated what was happening, misinterpreted the evidence or confused mephedrone for the similar-sounding, but completely different, heroin-substitute methadone.

About mephedrone:

Mephedrone has a similar effect to amphetamines

Also known as meph, 4-MMC, MCAT, Drone, Meow and Bubbles

Often sold online as plant food marked "not for human consumption"

Normally snorted, though also found in pills and capsules

Reported side effects include headaches, palpitations, nausea, cold or blue fingers

Long-term effect of taking drug unknown

In fact what I had reported on was the tip of a drugs iceberg which included a range of new psychoactive substances, external (NPS), known as "legal highs", synthetic chemicals which mimic the effects of illegal drugs. They were legal to possess and supply, but had the potential to cause mood swings and sudden changes in behaviour.

The iceberg has continued to grow. In 2011, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the government's official drugs advice panel, said the advent of NPS had "changed the face of the drug scene remarkably and with rapidity", external.

By last year, Nick Hardwick, then Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, declared that NPS represented the "most serious threat", external to the security of the prison system.

And last week, the United Nations International Narcotics Control Board said the emergence of NPS, external was "undiminished" and a "public health challenge", with 602 new types of the drug reported in 2015 - 5% more than the year before.

The government's main response to NPS has been to outlaw them: 500 substances, including mephedrone, now fall under the Misuse of Drugs Act, external.

But if the aim was to stop the spread of NPS, then the approach has failed. As each drug is made illegal, the chemical structures are tweaked to create a new substance which falls outside the legislation.

The new substance is on the market so quickly that its health and social harms can't be assessed and action taken to disrupt the supply.

Radical approach

So, the government is trying something radically different - the significance of which has not yet been fully appreciated.

From 6 April, sweeping new powers, external will come into force in the UK making it an offence to produce or supply any substance intended for human consumption that can produce a psychoactive effect.

It's a reversal of the current system, under which drugs are prohibited only after they've been identified, tested and evaluated. In future, the only psychoactive substances that won't be banned are those that have already been specifically excluded. People who break the new law could find themselves jailed for seven years.

New psychoactive substances can be deadly

Given the blanket nature of the measures and the severity of the possible sanctions it is not surprising they had a rather turbulent passage through Parliament.

Some have compared the law to the Dangerous Dogs Act, the infamous 1991 legislation, drafted at speed in response to a string of attacks on people by aggressive dogs.

One problem is the term "psychoactive substance". It is defined in the Act as something that "affects the person's mental functioning or emotional state", a description that appears to be deliberately wide and vague.

How would it be applied to new substances whose psychoactivity has yet to be tested? Could harmless herbal products or strong spices be caught up? Expect a few courtroom battles over that.

Another difficulty is the exemptions list: alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, medicines, food, drink and drugs that are already controlled are on it.

But "poppers", chemicals popular among gay men to enhance their sexual experience, are not - a decision described as "fantastically stupid" by Conservative MP Crispin Blunt, a poppers user., external

Crispin Blunt admitted he used poppers

A third issue relates to sentencing. Although people caught with NPS for their own use won't be punished, the penalties for production and supply don't, on the face of it, appear to distinguish between different types of psychoactive substances, a concern raised by the Home Affairs Committee and in the House of Lords.

That may well lead to a stream of appeals by those who feel they have been unfairly sentenced, though the Home Office says sanctions will be proportionate to the drugs which cause the most harm.

Of course, the fact that NPS will be subject to an automatic ban and possible criminal sanctions is likely to send a strong message about the dangers of the drugs - and may act as a deterrent: greater public awareness of the risks is one of the aims of the legislation.

But will the measures themselves succeed in reducing availability and consumption?

Even the Home Office acknowledges there is no hard evidence yet to support that from the countries with comparable systems - the Republic of Ireland, Romania and Poland.

In its "impact assessment" document about the measures, prepared in May 2015, officials said "no formal evaluation" had been completed in any of the three nations, though it pointed out that hundreds of head-shops, which are thought to have sold NPS, had closed.

The BBC later reported, however, that Irish police found it hard to bring prosecutions under their new legislation - a problem which could also beset British law enforcement agencies, given the law has been modelled on Ireland's.

Alternative sources

The Home Office impact assessment says there is "considerable uncertainty" about the impact of the ban on businesses which sell NPS because they occupy a "grey area" between the licit and illicit drugs markets.

It accepts there is a risk users will turn to the internet and organised crime groups to obtain NPS, or even switch to substances that are banned under the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Nevertheless, it estimates there will be 12 fewer NPS-related deaths each year - though quite how officials arrived at that figure is unclear.

Nick Hardwick warned legal highs were a threat to the prison system

If lives were to be saved, health costs reduced and harm to communities diminished, the architects of this ground-breaking legislation would no doubt claim it to be a success.

In England and Wales in 2014, there were 67 deaths linked to new psychoactive substances - treble the number in 2010, when I made that visit to Guernsey.

But NPS are just a small part of a far bigger drugs problem which claimed 3346 lives in 2014. Most of the deaths were caused by the abuse of opiates such as heroin, cocaine, amphetamines and tranquilisers.

According to the Office for National Statistics it was the highest number of drug-related deaths since comparable records began in 1993.

That alarming fact makes the need for a renewed focus on the drug problem more urgent than ever - indeed, the Home Office is "refreshing" its five-year drugs strategy, with a new version to be published in the coming weeks.

But the new strategy is likely to be similar to what is already in place, which is why there will be more attention on the hugely controversial Psychoactive Substances Act: the critics will be watching closely.

- Published23 October 2015