Operation Midland ends: What next for child abuse investigations?

- Published

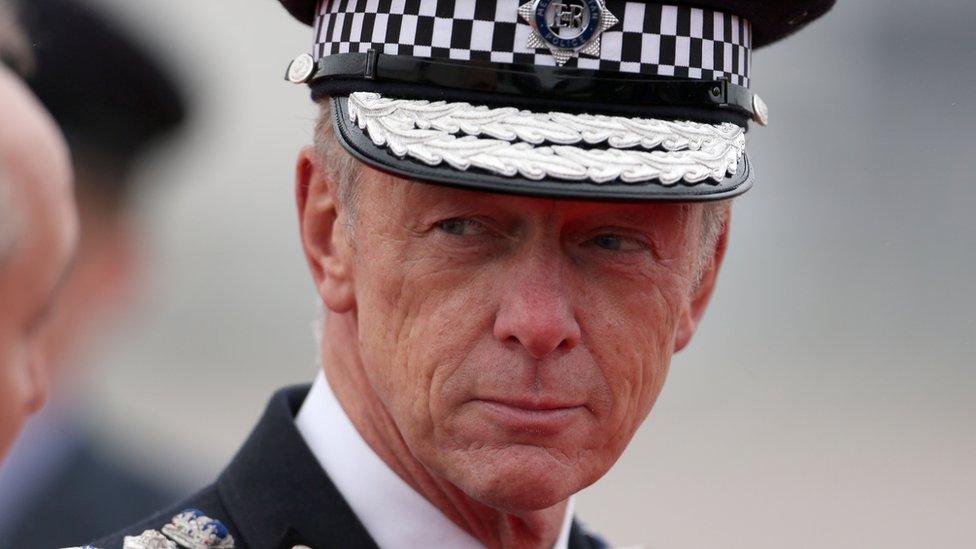

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe faced calls to resign over Operation Midland

Five words signalled the end of one of the most controversial investigations into child abuse ever conducted by police: "Operation Midland has now closed."

But those words - contained in a detailed statement issued by Scotland Yard on Monday afternoon - raise more questions than answers.

Will police continue to dedicate resources to non-recent allegations of abuse? Has their approach to such cases changed? And what's the impact on the Metropolitan Police and its Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe?

In terms of Sir Bernard, his immediate future is secure - despite calls from Harvey Proctor and others for him to resign, external.

In February, the commissioner was granted a one-year extension to his five-year contract, which will make him the longest-serving Met chief since Sir Paul Condon, who was at the helm from 1993 to 2000.

Leadership tested

The contract decision was taken by Theresa May, the Home Secretary, who took advice from London's Mayor, Boris Johnson.

It was a reflection of the 58-year-old Yorkshireman's wider record at the Met, tackling crime and terrorism, making budget savings and rebuilding trust in the force after allegations that police officers passed confidential information to journalists and failed properly to investigate phone hacking.

However, Operation Midland has undoubtedly tested the commissioner's leadership and judgement. A detective's ill-judged comment that the complainant's allegations were "credible and true" stoked criticism of the inquiry.

What was Operation Midland?

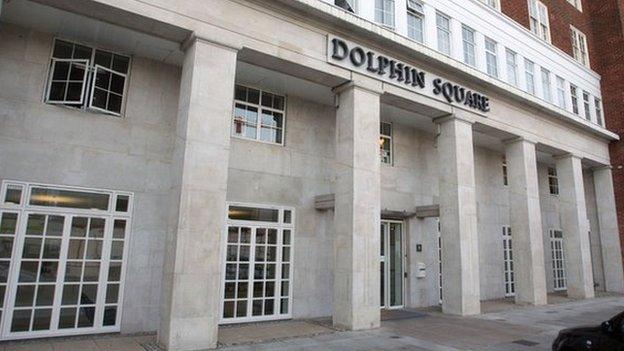

Established in November 2014, Operation Midland was set up to examine historical claims of a Westminster VIP paedophile ring, with allegations that boys were abused by a group of powerful men from politics, the military and law enforcement agencies.

The inquiry was also intended to examine claims that three boys were murdered during the alleged ring's activities. Operation Midland related to locations across southern England and in London in the 1970s and 1980s, and focused on the private Dolphin Square estate in Pimlico, south-west London.

In February, Sir Bernard responded by announcing a judge-led review of abuse investigations and calling for a new approach so officers don't "unconditionally" believe what victims say.

That sparked a war of words with Sir Tom Winsor, the Chief Inspector of Constabulary, who said that unless police initially believed allegations they wouldn't record them properly and therefore wouldn't investigate them.

Amid concern that if police rowed back from "believing" victims it would deter them from coming forward, the College of Policing has now clarified the issue, external, writing to chief constables and police and crime commissioners about the need to "further improve" the confidence of victims to report allegations.

In the confusing aftermath of Operation Midland, the College of Policing letter shows police the way ahead: believe the account given by a victim unless there's credible evidence that no crime has been committed, then carry out a thorough investigation to prove or disprove the allegations.

There's nothing new about the guidance - it's there already in police, Crown Prosecution Service and Home Office manuals - but it clearly needed restating.

Wave of allegations

The more urgent question now is how police cope with the tide of sexual abuse allegations that shows no sign of receding.

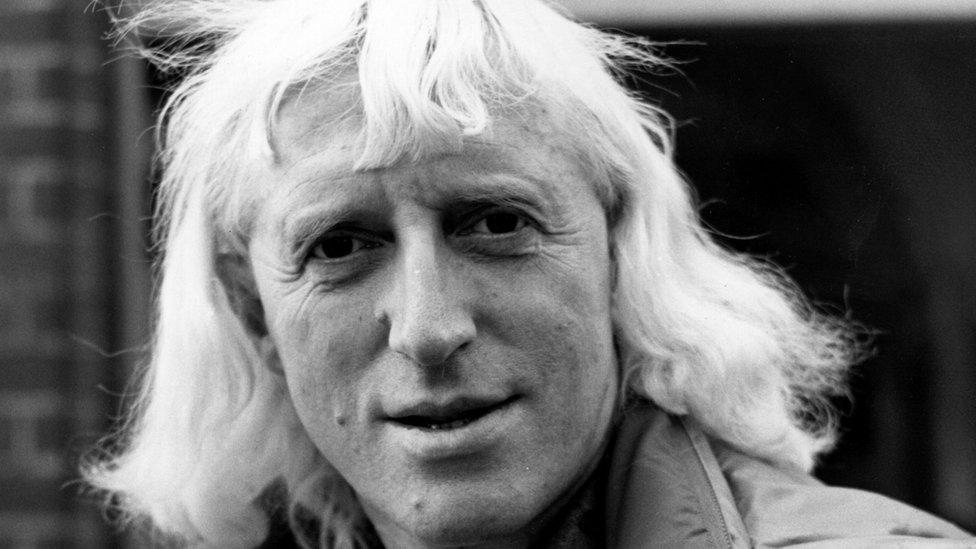

Revelations about Jimmy Savile have led to other survivors of abuse coming forward

Between 2006 and 2012 the number of sexual offences recorded by police in England and Wales was steady, at around 50,000 to 55,000.

But that autumn, the revelations about Jimmy Savile, together with appeals to victims to come forward, emboldened other survivors of abuse to report what had happened and the numbers have increased every year since.

According to the latest data, for the 12 months ending in September 2015, there were a record 99,609 sexual offences reported to and logged by police, although some of the rise is due to improvements forces have made in the way they process allegations.

However, there's no sign that the increase is slowing. Chief Constable Simon Bailey, the national policing lead on child protection and abuse investigation, believes this is partly due to a genuine rise in cases, facilitated by the internet, rather than simply a greater willingness of victims to come forward.

He told The Times police could be investigating 200,000 cases of child sexual abuse by 2020 if the numbers continue to go up at the present rate.

With police budgets remaining stretched, forces will have to make difficult decisions about where to spend resources.

Victims who are at risk now and suspects who are at large now will be the priority. Historical cases, however awful the alleged abuse, however powerful the alleged abusers, may have to wait their turn.

- Published21 March 2016

- Published21 March 2016