Eurozone crisis 'pushing migrants to UK'

- Published

The eurozone jobs crisis is encouraging more southern European migrants to head to the UK to join those from the east, the Migration Observatory has said.

Over the past five years the number of EU nationals living in the UK has gone up by almost 700,000 to 3.3 million.

The report said 49% of the 700,000 were from Poland and Romania,, external but Spain, Italy and Portugal accounted for 24%.

The Migration Observatory says there is no single "pull factor" but a mixture, including wages and economic prospects.

Just over 70% of EU citizens coming to live in the UK for at least a year say they are coming to work, with more than half of them already having a job to start.

The Migration Observatory research team at Oxford University said it had tried to identify the domestic and international triggers behind migration from the EU over the past five years.

While the UK had experienced huge movements from eastern Europe, particularly from Poland, southern Europeans were now looking for work in the UK to avoid the economic crisis at home.

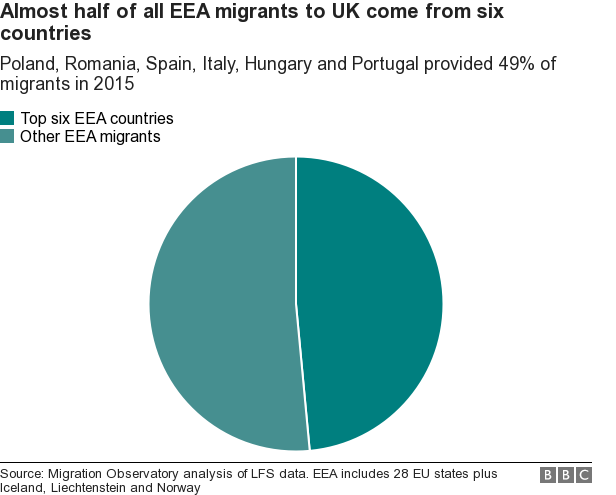

An analysis of official figures shows six countries provided almost half of all EU nationals in the UK - Poland, Romania, Spain, Italy, Hungary and Portugal.

The number of people from those six nations living in the UK had gone up by more than 500,000 between 2011 and 2015. During the same period, Spain, Italy and Portugal together had lost almost a million jobs.

Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory, said the rise in southern European arrivals indicated that the reasons why people moved differed depending on their origins - and could also change over time.

"There is no single factor driving high levels of EU migration in recent years," she said.

"Some drivers are likely to remain in place for some years, such as the relatively low wages in new EU member states, particularly Romania.

"Others could potentially dissipate more quickly, like high unemployment in Spain.

"Migration may respond more to factors that governments don't directly control, like demographics and economic growth in other EU countries."

Austerity: The Eurozone crisis led to mass emigration of young workers from Portugal

The view from Portugal: Alison Roberts, BBC News, Lisbon

In Portugal, hundreds of thousands of workers have left in recent years, many well qualified youngsters such as nurses. There are worries about a brain drain, although some argue that high fliers will return, with valuable experience.

The International Monetary Fund, in a recent report on post-bailout Portugal, described as a "fundamental problem" the shrinking of the workforce with ageing and emigration.

Economic recovery might have stemmed the outflow, but so far has not.

Just before October's general election, with emigration a hot campaign topic, figures from an emigration watchdog at a Lisbon university confounded expectations: some 110,000 people left in 2014, similar to 2013.

Not only the jobless left, but also people lacking job security. Given that, there is much uncertainty about current trends.

With Brazil - a traditional destination - in crisis, fewer are heading there, many more to Spain and above all the UK.

This week, representatives from Portugal's largest union federation, the CGTP, joined counterparts from Poland and the TUC in Norwich to discuss migration trends and related issues.

Brexit campaigners say the UK's benefit rules act as a magnet for foreign workers.

The government says its recent deal with other EU member states means it will be able to pull an "emergency brake" to withhold in-work benefits from future migrants, reducing the incentives for them to come in the first place.

However, the Migration Observatory analysis found no clear evidence of the role that benefits might be playing in those arrivals.

EU migrants are more likely to be in work and therefore less likely to claim jobseeker's allowance, says the research.

At the same time, they are more likely to be claiming tax credits supplementing the income of low-paid families.

The research says it is difficult to predict what effect the National Living Wage, which is designed to progressively rise until 2020, will have on EU employment.

"If higher wages encourage employers to restructure their workforce and reduce their reliance on low-wage workers - for example by mechanising production or hiring people with higher qualifications or skills - this could potentially make it harder for EU citizens to find low-wage jobs," the report says.

Another long-term factor that could influence the rate of migration to the UK is the birth rate in Europe.

The population of 20 to 34-year-olds in the six top nations has fallen by more than six million - or 15% since 2006.

If those fall continue, it could lead to a corresponding decline in the number of workers willing to travel to the UK as demand for them at home, and wages, increase.

Immigration and the EU: For and against

Leave campaigners say: Britain would regain full control of its borders. UKIP wants to see a work permit system introduced, so that EU nationals would face the same visa restrictions as those from outside the EU, which it says would reduce migration numbers. This would create job opportunities for British workers and boost wages, as well as easing pressure on schools, hospitals and other public services, they say.

Remain campaigners say: Britain might have to agree to allow free movement of EU migrants as the price of being allowed access to the free market. In any case, pro-EU campaigners argue, immigration from the rest of the EU has been good for Britain's economy. The UK's growth forecasts are based, in part, on continued high levels of net migration. The Office for Budget Responsibility says the economy relies on migrant labour and taxes paid by immigrants to keep funding public services.

Stephen Parkinson, of Vote Leave, which is campaigning for Britain to leave the EU in June's referendum, said the Migration Observatory's report "tells us what we [already] know".

"People come to the UK for a variety of reasons - not, as the prime minister has claimed in the context of his renegotiation [with EU leaders], because they want to claim benefits," he said.

"There's nothing in his renegotiation deal that will help us to control numbers."

Will Straw, of Britain Stronger in Europe, agreed that the report confirmed "what we already know" and said the question now was how to respond.

He said David Cameron's renegotiation had delivered a "brake on people coming here and getting immediate access to benefits" - and this would "reduce one pull factor".

He added: "Most people think that if people come here, work hard, pay their taxes and contribute they should be welcomed."

- Published26 May 2016