Palmyra's Arch of Triumph recreated in London

- Published

Boris Johnson unveiled the structure in Trafalgar Square

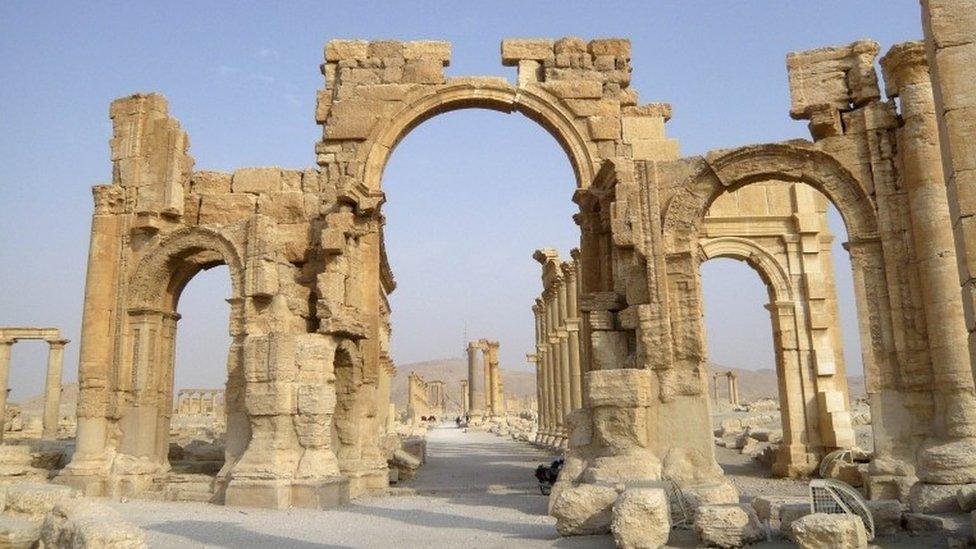

A replica of a Syrian monument, two millennia old and destroyed by so-called Islamic State in Syria, has been erected in London's Trafalgar Square.

The scale model of the Arch of Triumph has been made from Egyptian marble by the Institute of Digital Archaeology, external (IDA) using 3D technology, based on photographs of the original arch.

It will travel to cities around the world after leaving London.

Syria's director of antiquities said it was an "action of solidarity".

Unveiling the structure, London Mayor Boris Johnson said the replica was an arch of "technology and determination".

He told spectators they were gathered "in defiance of the barbarians" who destroyed the arch in the city, north-east of the Syrian capital Damascus, last year.

'Common heritage'

The original arch was built by the Romans.

The two-thirds scale model will be on display at Trafalgar Square for three days before moving to other locations around the world, including New York and Dubai.

It is intended that it will then be taken to Palmyra next year, to find a permanent home near the original arch, said Roger Michel, executive director of the Oxford-based IDA.

The monument was recreated using 3D modelling technology

"It is a message of raising awareness in the world," said Maamoun Abdulkarim, Syria's director of antiquities who was in London to watch the replica being installed.

"We have common heritage. Our heritage is universal - it is not just for Syrian people."

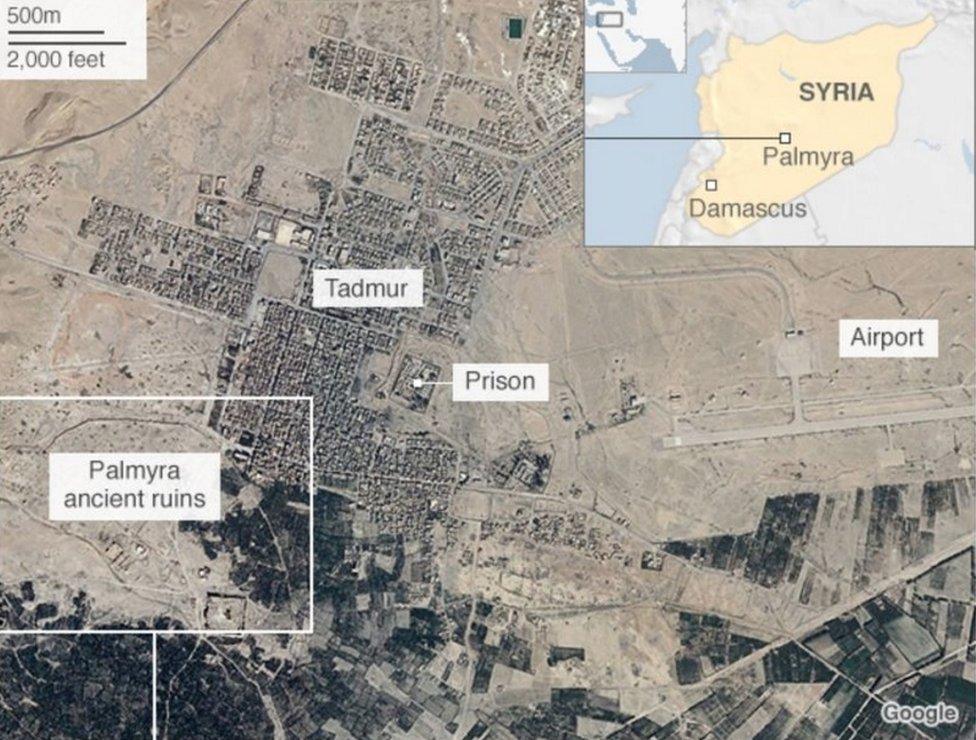

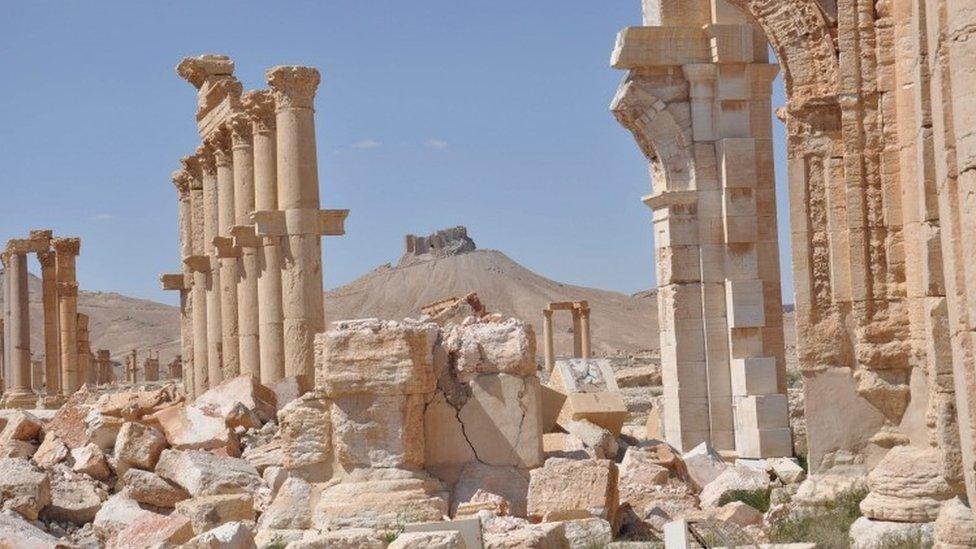

Palmyra, and its complex of ancient ruins, was recaptured at the end of March, having been overrun by IS militants in May last year.

At least 280 people were executed during their occupation of the city, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group.

Mr Abdulkarim, who visited Palmyra a week after its liberation from the Islamic State group, also known as IS, Isis and Daesh, said about 80% of the ancient monuments remain.

He stressed that the purpose of the project was restoration, using the new technology and the remains of the site to rebuild the ancient monuments, rather than creating them afresh.

"We can never have the same image as before Isis," he said. "We are trying to be realistic.

"But what we want to do is respect the scientific method and the identity of Palmyra as a historic site."

It took about five hours for the replica to be put in place in central London

Mr Michel said that when Palmyra was attacked, he decided the IDA's Million Images Database project - which distributes 3D cameras to volunteers in countries including Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq - could take action.

"It is extraordinary to have a vision about something and see it come together in such a palpable way," he said.

The 5.5m-high replica was made by machines carving the stone to the exact shape and design of the original arch, based on 3D photographs.

Ancient city of Palmyra

Site contains monumental ruins of great city, once one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world

Art and architecture, from the 1st and 2nd centuries, combine Greco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian influences

More than 1,000 columns, a Roman aqueduct and a formidable necropolis of more than 500 tombs made up the archaeological site

More than 150,000 tourists visited Palmyra every year before the Syrian conflict

Mr Michel said he wanted London to be the first to house the replica because the city itself had been reconstructed after World War Two, and that he hoped "anybody who appreciates free speech" would understand why it was so important to recreate the arch.

Citing the economic importance of the site to Syrians, he said: "It doesn't mean because you mourn the loss of life that you should leave your country in ruins. No-one can bring back the dead, but you can improve the lives of the living."

He added: "This is about censorship, in my opinion. If there are folks in the world who want to delete things from the historical record, they need to be restored. It's as simple as that.

"This is not any different from book-burning. This is an attempt by folks to exorcise portions of history."

The placing of the arch is intended to echo the architecture of the National Gallery behind it

But Professor Bill Finlayson, of the Council for British Research in the Levant, which supports research into the archaeology of the region, sounded a note of caution.

"The publicity and so on is great," he said. "I have no problem with this [project].

"I think there is a bit more of a problem with the issue of reconstruction on the site itself.

"The dangerous precedent suggests that if you destroy something, you can rebuild it and it has the same authenticity as the original."

The installation of the replica, which cost about £100,000 to create, has taken place during World Heritage Week.

Dr Robert Bewley, a specialist in endangered archaeology at Oxford University, agreed it was important the reconstruction did not diminish the significance of the original monument - and there would always be a "questions of value for money" of reconstructions.

"But if wealthy philanthropists wish to create these symbols of the cultural heritage, to raise awareness of the destruction of identity and cultural heritage then that is their right," he added.

'Not making a statement'

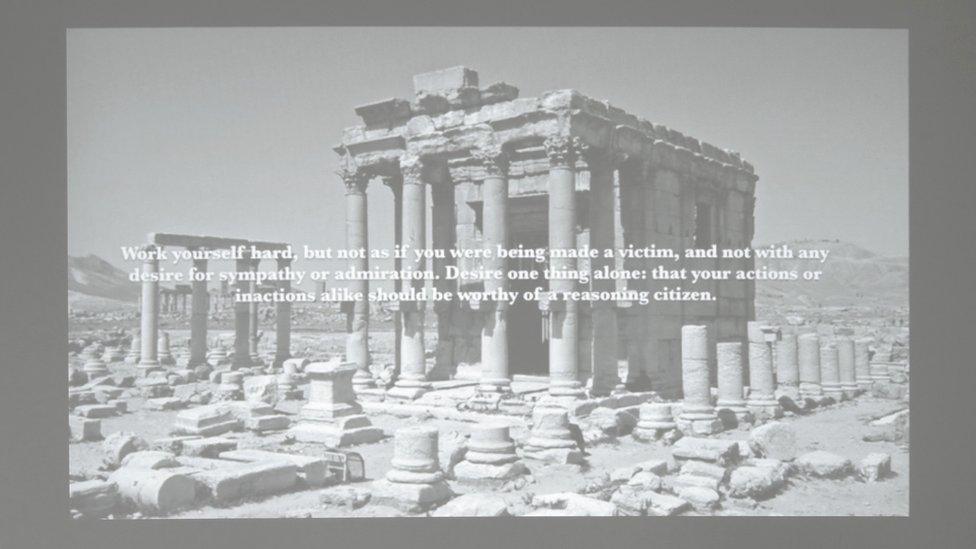

Coinciding with the installation of the arch is The Missing: Rebuilding the Past, an exhibition claiming to be the first to "showcase the efforts of artists and scholars who resist the destruction of cultural heritage" carried out by IS.

Jessica Carlisle, who is hosting the show at her central London gallery, which includes a 3D printed model of the Arch of Triumph, said their response "challenges the very notion of loss".

She said: "Artists and scholars wanted to do something positive, to say that what is happening is terrible, but let's celebrate the creativity coming out of it, and the people challenging what Isis are doing."

James Brooks' work projects quotes from Marcus Aurelius onto images of Roman ruins in Syria

One of the most visually striking pieces at the gallery is by British artist Piers Secunda, who creates moulds of bullet holes made by so-called Islamic State militants and casts them in replicas of ancient reliefs.

His piece displayed at the gallery shows bullet holes from a school in Iraqi Kurdistan, where he had travelled to two weeks before the Paris terror attacks, the village having been liberated from IS only weeks previously.

He says of his work: "It's about capturing the texture of geopolitics. It's not making a statement, it's making a record."

Piers Secunda's work, Isis Bullet Hole Painting, is among works "making a record"

The exhibition also features a model of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus made by 25-year-old Tmam Alkhidaiwi Alnabilsi, a Syrian currently living at the Zaatari camp outside Jordan.

It was made by Alnabilsi as part of a community art project, out of a variety of materials including kebab sticks.

Tmam Alkhidaiwi Alnabilsi used a variety of materials, including kebab sticks, to make a model of a mosque in Damascus

"I think it was a really cathartic thing to do in the camp," said Ms Carlisle. "It's very poignant. I was very emotional opening the crate when it arrived at the gallery."

The Missing was previously on show at New York's Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, with the London exhibition featuring some of the same works.

Erin Thompson, a professor of art crime, curated the exhibition as a response, she said, to the "dominant image in the Western media... that we were helpless to prevent any of the destruction".

She described reacting in such a way was "doing Isis's propaganda for them".

Instead, she decided to find artists who were "creatively reacting to this destruction", and said people had been "extremely moved" by the show.

Ms Carlisle said: "I hope people see the positive message in this.

"For me, it is a celebration of creative spirit and artistic endeavour, in the face of really unfortunate circumstances."

- Published2 April 2016

- Published28 March 2016

- Published28 December 2015

- Published5 October 2015