Oh, Doctor Beeching... if you could see us now

- Published

The train line at Dawlish runs right along the coast

Two people have been on my mind lately: Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Richard Beeching. Because of a combination of work assignments and family commitments, I've been taking the train between London and Devon quite often.

Rail was the broadband of its day, a faster form of communication than any of its predecessors, connecting the previously remote, creating opportunities for commerce and leisure.

In a county such as Devon, it was a messy business. The engineering challenge was formidable.

Last week, I sat on a train working its way along the southern coast. With the sea wall below my eye line, it was easy to imagine we were skimming the water itself.

You may remember the television pictures of this stretch of line, at Dawlish, swinging in the wind, the result of storm damage in February 2014.

It is hard not to be impressed by Brunel's audacity in constructing the line right on the very edge of the land.

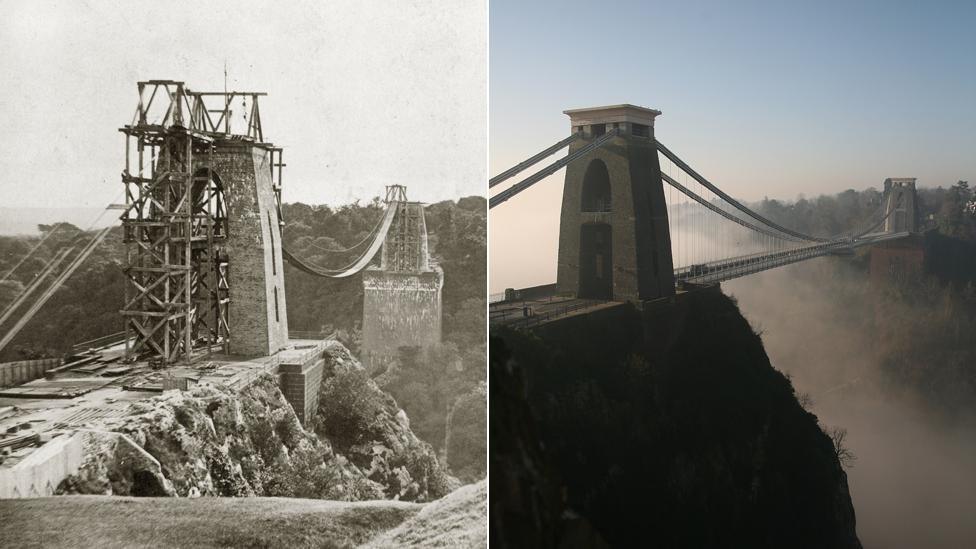

Brunel's influence on the English landscape is still evident today. The Clifton Suspension Bridge spanning the Avon Gorge was designed by him and completed in 1864 after his death

In his time, rivalry between the various companies hoping to exploit this vast new market resulted in competing lines.

In the sparsely populated north of Devon, there were two alternative routes for travellers, still in existence into the mid-1960s.

On their honeymoon, my parents travelled to London from a tiny village without having to change train once.

A decade earlier, the network had been nationalised. Company initials such as GWR (Great Western Railway), which to some speak of the romance of steam - God's Wonderful Railway, though contemporary travellers probably had their own less flattering versions - vanished, and gradually the route map shrank.

It is not hard to see why Richard Beeching reached the conclusion the network was unsustainable.

By the 1950s, the car was king, giving new freedom to the average traveller who until then had been at the mercy of someone else's timetable.

British Rail began losing money - £15.6m in 1956; four years later, it lost £42m.

As The Economist magazine reminded its readers recently, when the new town of Milton Keynes was being built it was constructed on a system of roundabouts - a new station was not deemed necessary,, external even though there would be hundreds of thousands of people moving into what had previously been an area of villages and small towns.

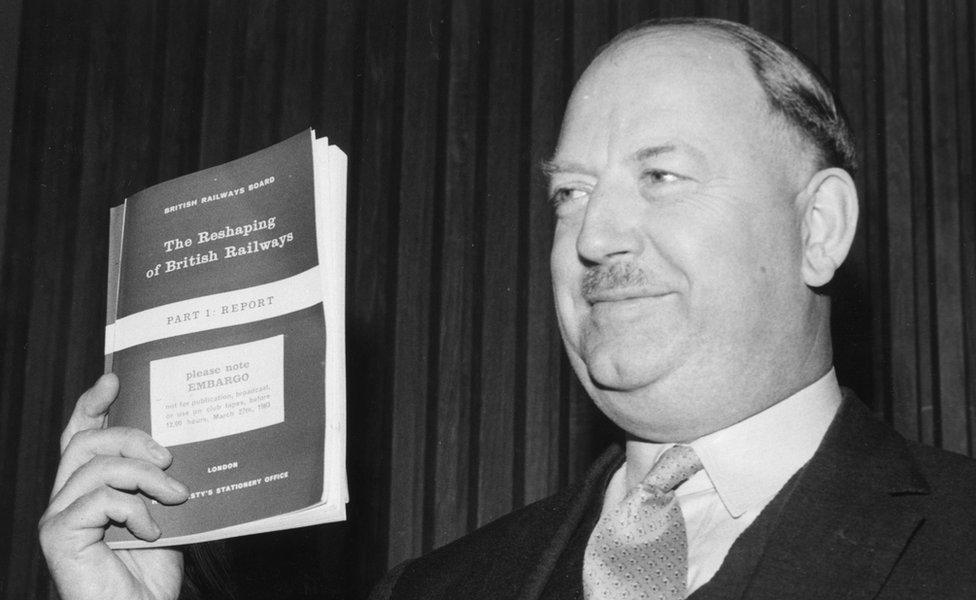

In his 1963 report, external, Beeching recommended closing one third of the track, and more than 2,000 stations. He insisted it was "surgery, not mad chopping", essential if rail was to become profitable, the instruction the government had given him.

Had his proposals been implemented in full, the railways would have linked large centres of population and important destinations for freight, but not much else.

Dr Beeching was chairman of the British Railways Board. He produced his controversial report in 1963

Although some closures proved politically untenable, in my native north Devon, as in so many other areas (and not just rural ones), the network withered.

By the late 1970s, when I first took a train to London, a long winding car journey was the prelude; the direct line to the nearest large station, Taunton, had been closed a decade before.

One local train service did survive, a branch line that dawdled slowly through the countryside between Barnstaple and Exeter.

In the summer, nipping between shade and sunshine under the dappled cover of trees, it was - and still is - a beautiful journey.

Stations such as Portsmouth Arms - named after the adjacent pub - remind you of the variety of functions rail used to serve.

Its existence, though, was precarious, and whether under state control or post-privatisation, its future always seemed to be in doubt.

The other local train was a ghost train. The Lynton and Barnstaple Railway did exactly what it said it did, delivering visitors to the picturesque village perched on the coast. But Beeching cannot be blamed for its closure. It had ceased to exist well before World War Two, the track ripped up, the engines and carriages sold off. Revival was a dream, nursed by enthusiasts with time on their hands, possessing ambition but little in the way of official support.

The BBC sitcom Oh, Doctor Beeching! was set in 1963 at and around the fictional Hatley Station, which was threatened with closure under the Beeching cuts

Yet something has happened since the 1980s that few would have predicted. Rail has made a comeback, and some of those ghost stations have been brought back to life.

When a new road was built across Exmoor, connecting the area to the M5 motorway, it stimulated demand from those wanting to live and work close by. Parkway rail stations, an early iteration of integrated transport, were designed to serve passengers who owned cars but didn't want a long commute.

With much fanfare, British Rail unveiled Tiverton Parkway, a new mainline station on the edge of Exmoor in 1986, while the new road was still under construction. The buildings were certainly new; the station wasn't. It had opened first as Sampford Peverell station in 1928, and been abandoned in 1964.

First Great Western, which runs trains in the south-west of England, recently launched its own appeal to the past. Some have derided its new livery as a marketing exercise - First Great Western had an unenviable reputation among some of its users. Still, God's Wonderful Railway, GWR, is running again.

First Great Western has rebranded as Great Western Railway

Branch lines, too, have enjoyed a revival. The Barnstaple-Exeter route is now known as the Tarka Line, a branding exercise aimed at tourists, the lifeblood of the region. Many stations, long since unmanned, now have volunteers to sweep the platforms, fill the flower baskets and shine up the heritage plaques.

The rolling stock is not quite so appealing - two or three old carriages that look like buses on the inside in the winter, supplemented during the summer with extra carriages and lots of room for tourist bikes and suitcases.

But looking out at the view the other day, it occurred to me how branch lines are one of the factors that can catalyse new development.

As broadband spreads, places close to a rail link become increasingly attractive areas in which to live.

The Economist reported that, as part of a deal to construct new housing in Tavistock, the developer is contributing £11.5m towards a rail link into Plymouth, restoring one of the Beeching-era cuts.

Of course, new demand creates tensions, and not just over construction.

The North Devon Journal recently carried a letter from an irate businesswoman, fed up with not being able to get home after late meetings in London.

She argued that intermediate stops should be cut out so the service could be speeded up and better integrated with the mainline at Exeter.

The regular customers - students, shoppers, those with jobs in Exeter - might not see the service in the same way.

Yet she and they share a common interest in ensuring it survives.

It is worth recalling that prominent incomers, including the late Lord George, the former governor of the Bank of England, helped to save the night sleeper service to Cornwall when it was slated for closure.

The Lynton to Barnstaple line closed in 1935, but part of the line - and Woody Bay Station - reopened in 2004

What of the Lynton and Barnstaple Railway? Local legend has it that it ran so slowly you could jump off at the front, pick flowers, and still have time to jump back on at the end. Progress in reviving it has been similarly time consuming, and there were plenty of sceptics locally who thought restoring it was a pipe dream.

Quietly, though, its supporters have been buying up parcels of land along the old line as they come on the market.

The appropriately named Woody Bay has a working station once again. It carried more than 48,000 passengers in 2015, if only for a distance of one mile.

Last month, a planning application was submitted to extend the line by a further four and a half miles, almost a quarter of the original length.

In 1963, Richard Beeching was probably correct in his analysis that the existing rail network could not be sustained.

Yet even heavily used commuter lines still struggle to generate commercially attractive rates of profit, and public subsidy is almost as ubiquitous as it ever was.

It is understandable that politicians and taxpayers think the cost should be borne increasingly by the user instead.

Still, rail is in part a community service and some communities would wither and die without it.

As I've both thundered and dawdled through the Devon countryside in recent weeks, the question on my mind has been whether conventional cost-benefit analysis gives proper weight to that.