US-UK: Strains on a special relationship

- Published

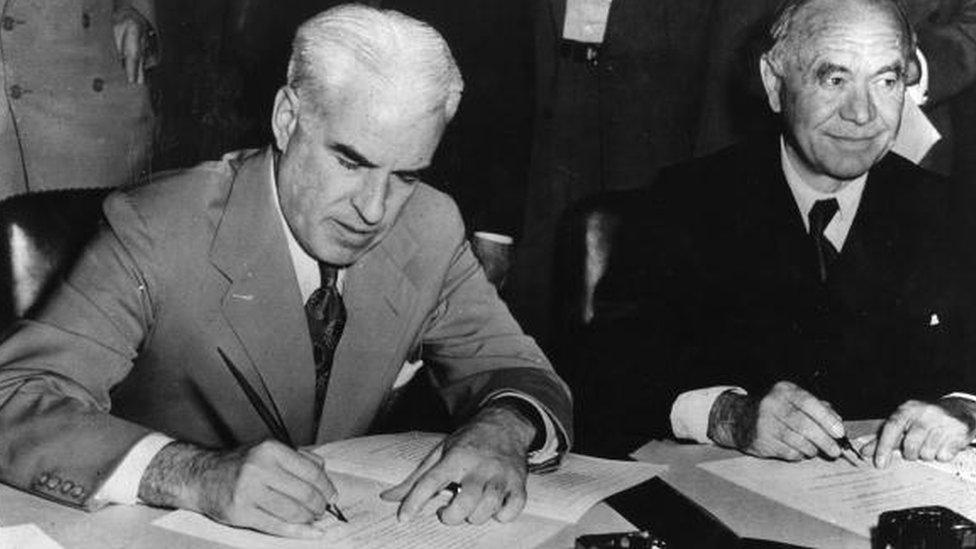

Churchill was a big advocate of the special relationship

The United States has long held views about Britain's place in the world.

Even before World War Two had ended, Washington was musing on how a victorious but exhausted Britain would adjust to a world where it had less power and influence.

The US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius wrote to President Roosevelt and said: "Never underestimate the difficulty an Englishman faces in adjusting to a secondary role after so long seeing leadership as a national right."

The Americans were uncertain of how Winston Churchill saw the post-War world and Britain's place in it.

In 1944, just before the Normandy landings, he had turned to General de Gaulle of France and told him: "Every time Britain has to decide between Europe and the open sea, it is always the open sea we will chose."

In 1946, during his famous speech, external in Fulton, Missouri, Churchill said: "Let no man underrate the abiding power of the British Empire and Commonwealth."

But, during the same period, Churchill was telling an audience in Zurich, external: "We must create the European family in a regional structure, called, it may be the United States of Europe."

What was far less clear was whether he intended Britain to be part of this new structure.

Edward Stettinius said Britain had difficulty adjusting to its diminished role in the world

The US and Britain had been the closest of allies - but, after the War, Washington, indisputably, had become the indispensable nation.

Sometimes - as over the partition of Palestine - British objections were simply ignored.

By 1952, the White House was becoming increasingly frustrated at what it saw as British attempts to undermine the emerging rapprochement between France and Germany.

Washington no longer saw Britain as a world power.

It wanted London (and Paris) to relinquish their former colonies to avoid the Soviet Union increasing its influence through support of liberation movements.

Suez crisis

All of this came to a head with the Suez crisis, which would mark the end of Britain's imperial influence.

France and Britain acted independently of Washington and sent troops to seize the Suez canal, which the British Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, had spoken of as Britain's "great imperial lifeline".

The US was not informed of the military operation.

President Eisenhower used the crisis to demonstrate how power had shifted in the post-War world.

He refused to allow the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to grant Britain emergency loans unless it called off the invasion.

Dean Acheson said Britain was struggling to find a role

Britain, militarily, never acted again against the explicit wishes of Washington.

Increasingly, it saw its influence in the world as dependent on a special relationship with the United States.

France drew a different lesson - that Europe needed to become a power in itself.

Long-lasting president and prime minister combinations since the War:

1945-50: Harry Truman (Democratic) and Clement Attlee (Labour)

1957-60: Dwight Eisenhower (Republican) and Harold McMillan (Conservative)

1961-63: John Kennedy (Democratic) and Harold McMillan (Conservative)

1966-69: Lyndon Johnson (Democratic) and Harold Wilson (Labour)

1970-74: Richard Nixon (Republican) and Edward Heath (Conservative)

1976-79: Jimmy Carter (Democratic) and James Callaghan (Labour)

1981-89: Ronald Reagan (Republican) and Margaret Thatcher (Conservative)

1993-97: Bill Clinton (Democratic) and John Major (Conservative)

1997-2001: Bill Clinton (Democratic) and Tony Blair (Labour)

2001-07: George W Bush (Republican) and Tony Blair (Labour)

2008-10: Barack Obama (Democratic) and Gordon Brown (Labour)

2010-16: Barack Obama (Democratic) and David Cameron (Conservative)

By the early 1960s, the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, was still agonising over where Britain's interests lay.

"Shall we be caught," he asked, "between a hostile (or at least less friendly) America and a boastful but powerful empire of Charlemagne, now under French but later bound to come under German control."

But the US establishment was sure, even back then, that Britain's place was in Europe.

In 1962, the former US Secretary of State Dean Acheson told an audience at West Point that Great Britain "had lost an empire and has not yet found a role".

That observation stung the British establishment, but Acheson was determined to strip away any illusions, adding: "The attempt to play a separate power role - that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a special relationship with the US, a role based on being head of a 'Commonwealth' which has no political structure, or unity, or strength - that role is about played out."

For most of the period since then, Washington has wanted the UK to be a cornerstone of the Atlantic Alliance, rooted in European institutions.

Where the UK was different to its European neighbours was in intelligence sharing with the US.

That remains the case today and, indeed, is a "special" relationship.

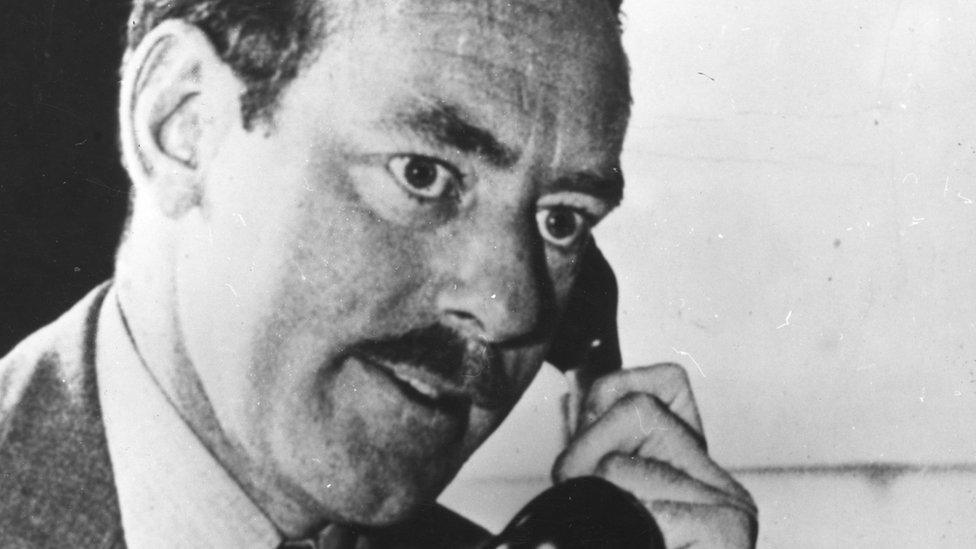

Harold Wilson was pressured by Lyndon Johnson to send British troops to Vietnam

There were always strains, however. During the 1960s, Harold Wilson came under enormous pressure to send British troops to Vietnam. He refused.

After one call, he said: "Lyndon Johnson is begging me even to send a bagpipe band to Vietnam." Wilson stayed out of the Vietnam conflict, at least overtly.

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were political soulmates. They rode horses together, shared golf buggies and paraded their friendship.

"Your problems," said the British prime minister, "will be as our problems, and when you look for friends we shall be there."

But that didn't stop her publicly berating the US president over the invasion of Grenada.

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were political soulmates

Tony Blair was an American-style politician who sought a close embrace from Washington. President Clinton was invited to a Labour Party conference in Blackpool.

In 2003, despite having developed warmer relations with Brussels, he broke with France and Germany and supported President George W Bush over the invasion of Iraq.

In New York, the papers depicted Europeans who didn't support the invasion as weasels.

In that period, President Bush said: "The United States has no truer friend than Great Britain."

Under the Bush administration, Britain was praised for its independence, its willingness to stand up to big challenges.

But Iraq descended into chaos and no weapons of mass destruction were found.

Tony Blair was criticised for being too close to George W Bush

Blair, at home, was called "America's poodle". In Britain, the desirability of the special relationship cooled.

Obama era

In Europe, they feted the arrival of Barack Obama. I watched 200,000 people turn out to welcome him in Berlin even before he had been nominated.

The Europeans embraced a leader committed to international institutions and the use of force as a last resort.

In 2008, I asked Mr Obama about the special relationship. He said he believed in it, but I sensed the question irritated him.

He did not want to be bound by such concepts. The US's interests tilted towards the Pacific - Europe was no longer the centre of American foreign policy.

And when there were crises - such as the problems with the euro and Russian aggression in Ukraine - it was German Chancellor Angela Merkel who got the first call.

President Obama might have accepted the US was the indispensable nation, but he has been reticent with the use of US power and frustrated at the failure of Europeans to share the load.

We now know he was deeply frustrated with the Europeans and David Cameron that they did not follow through the Libyan operation to remove Col Gaddafi.

President Obama is quoted as saying Mr Cameron had become "distracted", external.

The US president used all the muscle of his office to insist UK defence spending did not fall below 2% of gross domestic product (GDP).

He is not alone in the US political establishment in venting his frustration that Europeans are "free riders". They crave influence in the world but through soft power. Hard power is left to the Americans.

Harold McMillan agonised over where Britain's best interests lay

Mr Obama, like presidents before him, wants Europeans to take more responsibility for their neighbourhood. That means higher defence spending and closer European cooperation.

That is where American interests coincide with David Cameron's referendum campaign to remain in the EU.

Even if President Obama does not tell the British people how to vote, his visit is one of the more unusual interventions by an American president during the past 60 years.

Washington believes Britain outside the EU would weaken the Atlantic Alliance and is prepared to say so.

Can Barack Obama and David Cameron continue the special relationship?

And the US trade representative Michael Froman has made it quite clear Washington would have no interest in pursuing a separate free-trade deal if Britain left the EU.

It would face the same tariffs and barriers as other countries outside the EU - such as China, Brazil or India.

US officials, of course, say they are acting in their own interest.

They believe a British exit would damage the global economy and weaken Europe during a turbulent period.

But the US is also sending the same message it sent after the War - although Britain is one of its closest allies with a far-reaching intelligence relationship, it sees its place in the world as part of the European project.

- Published11 March 2016

- Published11 March 2016

- Published21 September 2021

- Published22 May 2015