Do police have the firepower to tackle gun menace?

- Published

A police firearms officer perfects his technique on a firing range

At a firing range in Northampton, 14 policemen and women, each carrying a Glock 17 self-loading pistol, are on their first week of training.

They have volunteered to become firearms officers, a role that comes with no extra payment but huge responsibility.

Dressed in black police uniforms, and wearing goggles and ear defenders, they stand in a row, 10m (33ft) from a line of cardboard targets.

A police instructor bellows at them to get ready.

Seconds later, gunfire echoes around the building.

After each time they fire, the officers check the targets, plugging the holes where the bullets have gone with different coloured markers, to see if their aim is improving.

It is a deadly serious business. Like many other forces, Northamptonshire Police, part of a joint armed policing unit in the East Midlands, needs more firearms officers.

The latest official figures, for 2015, show the number across England and Wales fell to 5,647.

Research for BBC Radio 4's File on 4 programme shows this is the lowest level since at least 1987 - the year Michael Ryan shot dead 16 people in Hungerford, Berkshire.

And, after the attacks in Paris by gunmen last November, it became clear to senior officers they would not have enough firearms officers to deal with a similar strike in Britain.

'Replicating' Paris attacks

Deputy Chief Constable Simon Chesterman ran exercises for the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) "replicating" what had happened in Paris.

"Although we had some capability, we certainly lacked the capacity to respond effectively," he says.

Training at the police range in Northampton

As a result, the Home Office has agreed to fund 1,000 extra firearms officers for a period of five years.

Another 500 are being funded by local forces themselves - from within their existing budgets.

In Scotland, there are no firm plans to increase the number - they have 275 at present.

The Home Office says many of the new firearm officers will continue to carry out "core policing" roles, reducing the need to "backfill vacancies".

But Che Donald, from the Police Federation, which represents constables, sergeants and inspectors, is concerned the recruitment exercise will create a "gap" in the front line, as armed officers transfer from neighbourhood policing and CID.

"There isn't a magic pot we can just dip into and pull out a fully trained firearms officer," he says, pointing out that to take on 1,500 armed police, you need 3,000 to start with, because half drop out or do not pass the course.

Even with the extra numbers, there are doubts they could be deployed quickly enough to repel marauding gunmen.

Chris Phillips, head of the government's national counter terrorism security office until 2011, says the further away from city centres, the longer the response times.

Fourteen offices are put through their paces in Northampton

He believes many of Britain's energy and power plants - part of the critical national infrastructure - are vulnerable because they are "dotted around the coast" or in harder to access rural areas.

Once police have got there, the gunmen may have moved on.

"You can get to the first scene of the incident, but that may not actually be where the terrorists are," says Mr Phillips.

Simon Chesterman, from the NPCC, acknowledges the difficulties of mobilising armed units quickly, but says police would have support from the ranks of 3,000 firearms officers in the Ministry of Defence Police and the Civil Nuclear Constabulary.

Britain's armed forces would also play their part, says Mr Chesterman, possibly helping to move officers by helicopter and making soldiers available.

"If an event like this was to happen, you would expect special forces to deploy," he says.

"And following the event, it may well be that we'll request further military support from other military units."

Stray bullet risk

Mr Chesterman tells me that, under current plans, police would not be using fully automatic firearms to confront gunmen - even if the attackers were armed with machine guns.

He says there is too great a risk that if officers had automatic weapons, which can fire up to 800 rounds a minute, they would hit innocent people.

Officers are issued with single-shot firearms

Kevin Hurley, who until this month was Surrey's Police and Crime Commissioner, agrees stray bullets are a "danger", but says using single-shot firearms is a "flawed" approach.

"We're talking now about murder gangs armed with machine gun-type weapons," says Mr Hurley, an army reservist, who used to head the City of London police counter-terrorism unit.

"You have got to stop [them] immediately, and you've got to fire more bullets back at them so that you can move forward, otherwise you yourself will be killed."

Find out more

Listen to Danny Shaw's report for File on 4 at 20:00 on Tuesday, 17 May, or Sunday, 22 May, on BBC Radio 4, or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer.

The terrifying prospect police might be involved in a firefight with suicide bombers or gunmen has also prompted a debate about how such incidents would be investigated.

At present, police who shoot someone have to be able to show their actions are consistent with human rights laws.

Each bullet they fire must be "absolutely necessary" in the circumstances.

But Peter Squires, professor of Criminology at Brighton University and author of three books on armed policing, says justifying why firearms officers used lethal force could prove impossible for them in the chaotic aftermath of a marauding gun attack.

"Officers are going to be wide open to challenge every time they fired a shot," he says.

Michael Ryan

Hungerford massacre:

Unemployed Michael Ryan shot dead 16 people in a series of random shootings in the Berkshire town of Hungerford on 19 August 1987

He shot a handgun and two semi-automatic rifles at several locations, including a school he had once attended

Ryan later turned his gun on himself and was found dead inside the school by police

At the time, the incident was the worst mass killing of recent times in Britain

It led to tighter restrictions on gun ownership - including a ban on the ownership of semi-automatic rifles - with the introduction of the Firearms (Amendment) Act of 1988

Sarah Green, deputy chair of the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), accepts it would be "very challenging" to carry out an inquiry into a terrorism incident in which police had fired many shots at a number of different targets.

In virtually all police shootings it currently investigates - which are themselves extremely rare - no more than a handful of shots are fired at one or two people.

That could be very different in a marauding gun attack.

"We're not going to be marching in there and insisting that we start investigating in the middle of an ongoing situation," Ms Green says.

But, she adds, the IPCC still has a duty to conduct an inquiry and cannot just say, "We won't bother," because it would be tricky.

Even if hundreds of bullets have been discharged, the IPCC must understand what a firearms officer was thinking when they fired.

"We will be asking officers to provide accounts about the whole of their actions and why they did it," says Ms Green.

"It will come back to... what the officer's honestly held belief was at the time."

Legal protection review

The Home Office is now examining the legal protection for armed police, as part of a review ordered by Prime Minister David Cameron after the Paris attacks.

It is believed to be looking at the police practice of "conferring" - under which officers can pool their recollections of a serious incident, such as a shooting, when they write up their notes - following calls by the IPCC and the families of some of those who have died at police hands to stop it from happening.

The IPCC wants officers separated after a shooting until they have compiled their detailed account of what went on.

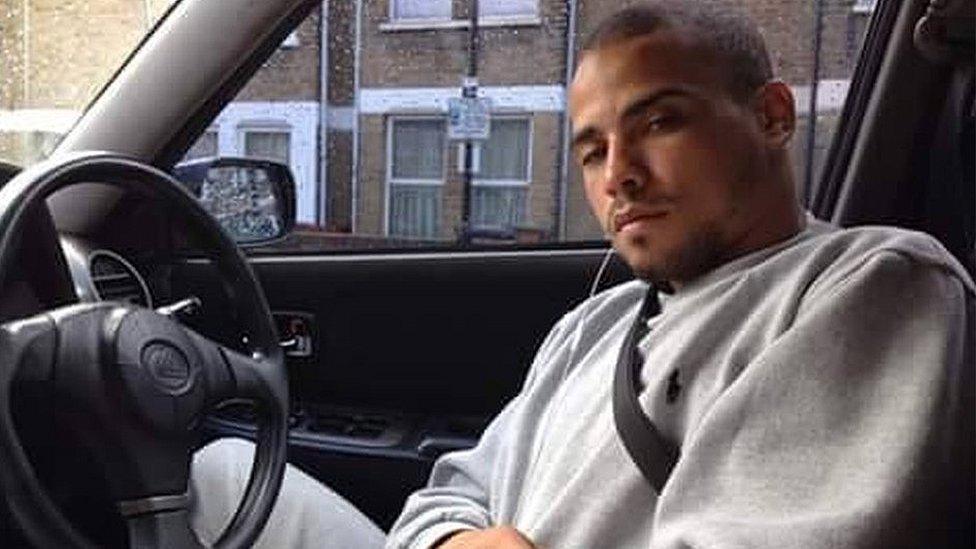

Jermaine Baker was shot dead by a Metropolitan Police firearms officer in north London

The review, which is shrouded in secrecy, is also considering police concerns about the IPCC's approach after 28-year-old Jermaine Baker was shot dead by a Metropolitan Police firearms officer in Wood Green, north London, in December.

In a highly unusual move, the watchdog set up a "criminal homicide" investigation and arrested the officer.

He is currently suspended while the inquiry continues.

Mr Chesterman says firearms officers are watching the case closely, amid concern they will be "automatically" suspected of wrongdoing if they shoot someone.

"There is a risk and a danger that as things develop, we may get less volunteers and that troubles me," he says.

The new recruits at Northamptonshire are warned - as are others elsewhere - they face intense scrutiny and many months, possibly years of investigation, if they do open fire.

At the moment, it does not appear to be deterring them from taking on the role.

There are still plenty of armed police volunteers - but that can change quickly.

- Published13 May 2016

- Published1 April 2016

- Published14 January 2016