Will ban on legal highs work?

- Published

Conservatives are usually opposed to the "nanny state" slapping draconian new rules on business or banning things that experts think might damage your health.

But today the government's delayed Psychoactive Substances Act comes into force, introducing powers over what consumers can consume that are as radical and far-reaching as any such legislation ever.

The intention is to solve the UK's problems with "legal highs" - chemical products not covered by existing legislation that are causing some health and social problems.

Legal highs have been implicated in 76 deaths in the last 10 years (31 where they have been the sole cause), the Office for National Statistics said last month.

However, that compares to 7,748 deaths involving illegal drugs, which has led some to question whether the government is using a sledgehammer to crack a nut.

Nevertheless, the Home Office's answer to the threat is to make it a crime to manufacture or supply such things.

It is clearly impractical to introduce separate bans for every new mind-altering drug that comes along (there are thousands being developed all the time), so the new law pretty much bans everything that can be called a psychoactive substance.

It is, basically, a ban on getting high.

The story of prohibition over the last 100 years is not a particularly happy one.

Banning alcohol in the US in 1920 pushed the trade underground, with criminals selling bootleg booze of dubious or dangerous quality.

Some 10,000 people died from drinking poisonous liquor before prohibition was lifted.

Many argue the so-called "War on Drugs" has done the same: Simply handing the trade to unscrupulous international criminal gangs.

Drug deaths in Britain are currently at record numbers.

But with no governmental appetite in Britain for decriminalisation or legalisation of drugs, prohibition remains the only response the Home Office is prepared to consider.

Ministers' first problem with prohibiting the trade in legal highs has been how to draft their ban so that cunning chemists cannot get round the law by tweaking the make-up of a substance to fall outside the latest list of illicit substances.

That's why they ended up with a law that, with a few notable exceptions, bans the manufacture and distribution of everything that is "capable of producing a psychoactive effect in a person who consumes it".

The notable exceptions include alcohol, nicotine and tobacco - not because they aren't dangerous and psychoactive, but because they are already so intertwined with our cultural and social lives.

Foods like chocolate and beverages such as coffee and tea are also exempted for similar reasons.

But the law seeks to prohibit the manufacture and sale of products with a "psychoactive effect" that may be far milder than a cappuccino or a Snickers bar.

Basically, the government is determined to stop people using any substance that causes an alteration in their state of consciousness - unless it is a large gin and tonic or a fat Cuban cigar, of course.

But banning almost anything that is "capable of producing a psychoactive effect in a person who consumes it" presented ministers with their next problem. How to prove that something does that?

My report from Ireland last year alerted many in the UK to a central problem with the law as it had been proposed.

The Irish government introduced a very similar blanket ban in 2010.

The head shops were closed down but online suppliers moved in and use of new psychoactive substances in Ireland is now the highest in Europe.

Police told me they were almost powerless to intervene because prosecutors could not prove in court that a substance was psychoactive.

British ministers were questioned about my report and set about trying to prevent similar problems with the courts here.

Finding an answer was not easy and the Act was delayed by more than a month while they worked on a solution.

Now the Home Office has come up with an answer: in-vitro testing.

Since you can't ask real human beings to take every dodgy looking product police seize to see if it has a psychoactive effect, the government has paid a commercial company to do a series of tests on existing legal highs in the lab (in-vitro).

The aim is to identify a range of chemical structures that can be shown to bind with cell-based receptors and to which the body then responds.

Cigarettes will not be included in the legislation

Having isolated a number of what are called Certified Drug Reference Standards (CDRSs), prosecutors will only have to get an expert witness to say that a product contains a known CDRS to prove to the courts that it is psychoactive.

Well, that's the theory.

But lawyers are already warning that this process has some tricky legal hurdles to clear.

The most obvious problem is convincing a judge that something achieved in a test-tube by a private testing company, paid for by the Home Office, will definitely happen in the human body.

For example, we know that the blood-brain barrier (BBB) protects the brain and spinal cord from neurotoxins while allowing other molecules to pass through.

It is far from clear whether in-vitro testing will be able to show whether the BBB will give a particular chemical passage into the central nervous system.

The Home Office tests will not provide information on the potency of a specific compound, either.

Indeed, the guidance says this is not possible or necessary, because the law does not differentiate between something that is 100% or 0.01% pure.

This means that a product that has such low potency it causes no noticeable psychoactive effect can still be described in law as having a psychoactive effect and banned.

Ministers are concerned that some legal highs don't act on the body by binding with receptors - but they want to ban those too.

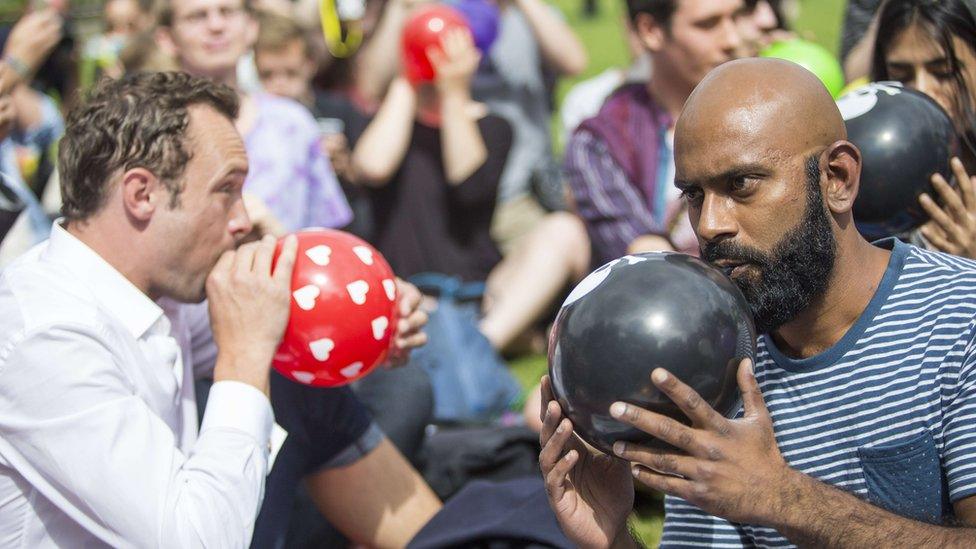

Substances like nitrous oxide and solvents cannot easily be subjected to in-vitro testing, so the guidance says prosecutions should be based on alternative sources of evidence including published literature and witness accounts of behaviour.

Defence lawyers might well question whether a paper in a scientific journal and a witness saying the consumer looked a bit dopey is enough to get a conviction.

Legal challenges are very likely in the early days of this act.

But it may be that over time a body of case-law and accepted science will mean prosecutions act as an effective brake on dangerous new psychoactive products.

The more troubling question, perhaps, is whether prohibition will once again hand the trade over to criminal gangs on the dark web, who are much more difficult to control than any High Street trader.

- Published26 May 2016

- Published26 May 2016

- Published25 May 2016