The UK women seeking divorce through Sharia councils

- Published

How the court hearing unfolded for "Yasmeenah"

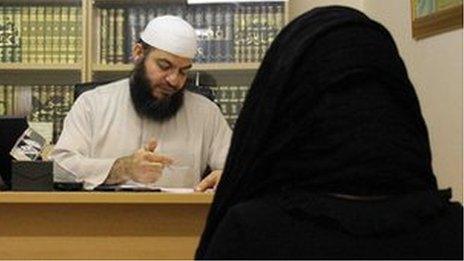

The use of Sharia councils in the UK to settle disputes using Islamic religious law has been criticised for discriminating against women. With rare access, the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme looks at what takes place inside one such council.

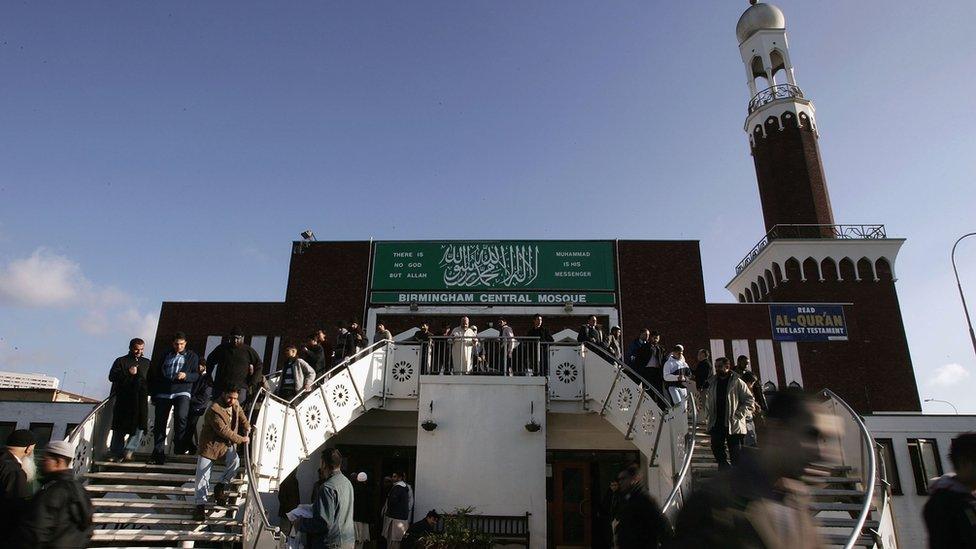

"Is it not possible to forget all the things he has done to you?" one of three Islamic scholars asks Yasmeenah - not her real name - in a side room of Birmingham Central Mosque.

Yasmeenah has been in an arranged marriage since the age of 15, and says her husband has emotionally and physically abused her throughout the relationship.

She has come to this Sharia council - one of an estimated 30 established councils across the UK, often referred to as Sharia "courts" - in the hope the scholars will grant her a divorce from her Islamic marriage, or nikah.

She dismisses the idea that she can overlook the past and continue the relationship.

The Sharia council at Birmingham's Central Mosque meet once a month

"But he loves you very much," the scholar continues, having spoken to her husband previously that day. "Yes, but this is not enough," she replies.

"Something makes me afraid of him and scared of him. If I see him, suddenly all my body starts shaking," she had explained shortly before.

The scholars listen to her case and, when they feel they have enough information, ask Yasmeenah to leave the room to allow them time to deliberate.

She returns nervously, but it is good news - the scholars have unanimously decided the marriage should be terminated with immediate effect, saying they are sad to hear what she has been through.

"When they announced [their decision] I felt that something happened that I had wanted for years," she explains, overjoyed. "I'm really surprised, because they cared about my emotions. I thought, 'Finally I've got my freedom.'"

Find out more

The Victoria Derbyshire programme is broadcast on weekdays from 09:00-11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

The courts' rulings, such as this one, are not recognised by the UK system, and these councils have no legal powers - although many of the women who claim they have been abused also go to the police.

The scholars' judgements, however, can carry moral and cultural weight by ending the divorce before God.

"If I went to an English court [my ex-husband] would say, 'Where is their right to decide about my life?' Now he can't say anything because the decision has been made using Sharia law, and we all believe in that," she explains.

'Discrimination'

There are claims, however, that some Sharia council decisions legitimise forced marriage and act unfairly towards women - although the council in Birmingham visited by the Victoria Derbyshire programme is regarded by many as one of the fairer councils.

"I am quite concerned [about Sharia councils], purely because of the cases we get on our helpline - and they come in regularly," says Shaista Gohir, chairwoman of the charity Muslim Women's Network UK.

She worries that women are being asked intrusive questions about their personal lives, and, in some cases, being discriminated against.

Shaista Gohir says she regularly hears accounts of women facing discrimination

Many incidents concern women being told to mediate with their husbands, against their will.

Aleena - not her real name - says she wanted a divorce because her partner used to rape her on a regular basis. He was also a polygamist.

"When I contacted my nearest Sharia council for a divorce they pressured me into mediation, which I didn't want.

"It arranged the mediation with one of its local religious advisers. I had to visit this man alone at his home. He asked me very personal questions about my sex life.

"He said that polygamy was allowed. He said, 'Be patient, you have lasted 22 years, why do you want a divorce now?'"

Another woman told us she was referred to mediation with her husband, even though "there were injunctions stopping him going anywhere near me".

Sharia

Sharia law can act as a code of conduct for all aspects of a Muslim's life

Sharia is Islam's legal system. It is derived from both the Koran, Islam's central text, and fatwas - the rulings of Islamic scholars. Sharia can inform every aspect of daily life for a Muslim.

Sharia councils aim to help resolve family, financial and commercial problems in accordance with Sharia principles.

The majority of cases involve women wanting to end their Islamic marriage.

There are an estimated 30 established Sharia councils in the UK, according to a 2012 study from the University of Reading.

Most councils operate from mosques. The first in the UK was established in Leyton, east London, in 1982.

In May, Home Secretary Theresa May said there was evidence some Sharia councils might be working "in a discriminatory and unacceptable way", and announced details of a review into Sharia in England and Wales.

Sources: Islamic Sharia Council, University of Reading

The Sharia councils are not regulated, so it can be difficult to assess what takes place inside - especially in some of the smaller councils that are not linked to mosques.

In May, the government announced an independent review to assess whether Sharia law in England and Wales was compatible with UK laws and whether it has been used to discriminate against women.

But Ms Gohir believes any recommendations it suggests will be difficult to enforce.

"Who is going to force these bodies to implement those recommendations," she asks. "There is no way of forcing them because most of them do not operate under the arbitration act anyway. So it might just be left to good will."

The Home Office says it can propose legislation should the review set out a clear case for it.

Amra Bone is the UK's first female Sharia council judge

The councils, however, believe they are providing an essential service.

Amra Bone, the UK's first female Sharia council judge, says without them, the women could feel trapped and oppressed.

Their Islamic marriages are often not legally binding and so can only be ended by one of these councils, rather than a civil court.

"If we left them [without the option of these councils] in miserable situations - where they're distraught, they don't know what to do, where to go - [they could] fall into deep depression," she explains.

Yasmeenah also sees the courts as something of a lifeline. "If the council wasn't here for me, what would I have done, how would I have got my divorce," she enthuses, as she pays the £300 it cost to bring her case.

But with a lack of consistent rules and standards, the councils do not work for everyone.

Ms Gohir believes that, if the rights of Muslim women were improved in wider society, they would not need to turn to such councils for a divorce.

"What I would like to see is civil solutions - and laws and policies strengthened - so Muslim women are less reliant on these Sharia councils. That would then - in the longer term, over 10 to 15 years - make a lot of them redundant."

- Published26 May 2016

- Published16 January 2012