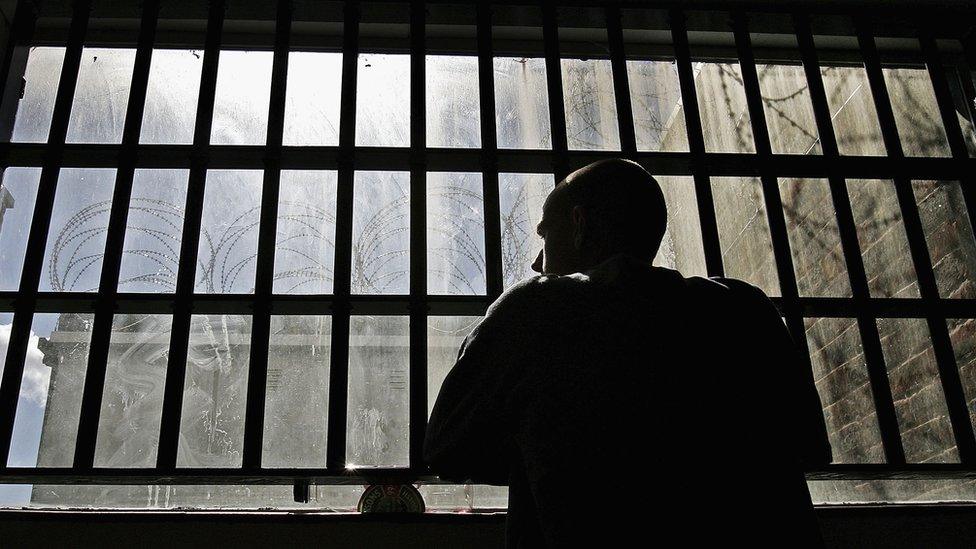

'Self-harming rise' among prisoners on indefinite sentences

- Published

The rate of self-harm by inmates serving indefinite prison sentences in England and Wales has risen by almost 50% in four years, figures suggest.

Last year, there were more than 2,500 acts of self-harm by prisoners serving imprisonment for public protection, or IPP, sentences, at a higher rate than among those serving fixed sentences.

The Prison Reform Trust said it showed IPP prisoners were in "despair".

The Ministry of Justice said it was urgently looking at IPP offenders.

IPP sentences were scrapped in 2012, but thousands of inmates are still waiting to be released.

'He cut his own throat' - Zoe Conway reports on self-harm in prison

According to new Ministry of Justice statistics, which were compiled by the Prison Reform Trust, external, there were 2,537 incidents of self-harm among the population of 4,100 IPP prisoners last year.

The figures suggest rates of self-harm among IPP prisoners have gone up significantly every year for the last four years.

'No finish line'

They showed there were 550 incidents of self-harm per 1,000 IPP prisoners last year.

That compares with 324 incidents per 1,000 prisoners on determinate sentences and 200 per 1,000 prisoners serving life sentences.

Of those still serving IPPs, 3,300 have served more than the minimum sentence they were given, while 400 have served at least five times the minimum sentence they received.

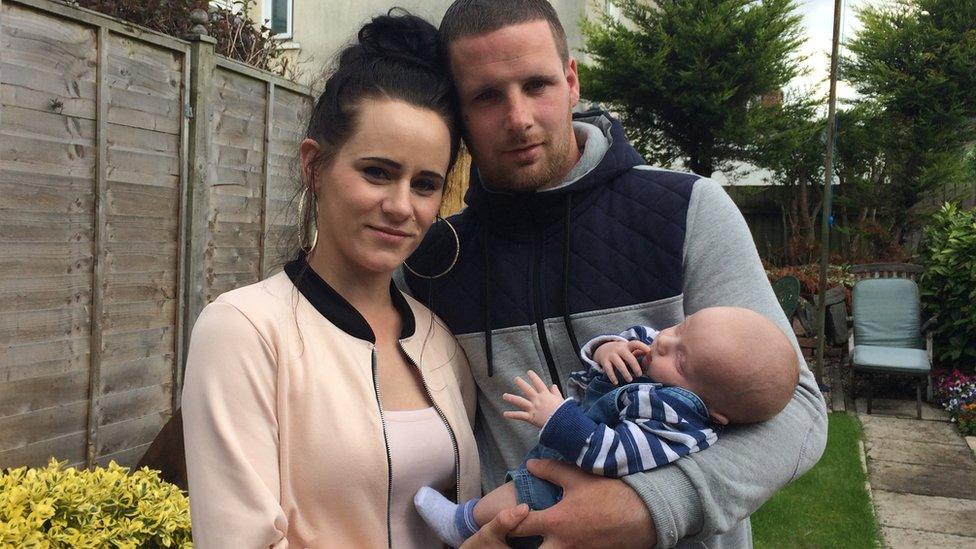

Case study

Danny Weatherson was 19 years old when he was given a 13-month IPP for robbery. More than nine years later, he is still in prison.

In February, a parole board said his re-offending risk had reduced sufficiently to be moved to an open prison.

But he cut his own throat last month and the move has been postponed. He is currently recovering in the prison's hospital wing.

His solicitor, Shirley Noble, says self-harming has become his way of coping with not having a release date.

But she is worried it could also hurt his chances of ever being let out.

Such behaviour could be considered risky by the parole board, and she says he is now trapped in a vicious circle. Describing the situation as ''extremely urgent'', she fears another act of self-harm could be fatal.

Ex-IPP prisoner Shaun Lloyd said the disproportionately high self-harm rate for IPP inmates was hardly surprising, since they lost hope because they "have no finish line to work for".

In order to be released, IPP prisoners must prove to a parole board that they are not a danger to the public.

However, Mr Lloyd said offender managers, who are responsible for assessing a prisoner's risk of re-offending, are over-stretched and might only spend a few minutes at a time with a prisoner.

"Clearly nobody can know you after seeing you twice and for just 10 minutes,'' he said.

He said under-resourcing was one reason why he had spent more than nine years in prison for street robbery, for which he had been given a minimum sentence of two-and-a-half years.

Shaun Lloyd said a shortage of offender managers was making the situation worse

The Prison Reform Trust says delays in the parole board system and limited resources are causing many prisoners to be held long after they have served the minimum sentence they were given.

Incoming director, Peter Dawson, said the figures showed "the growing toll of despair" IPP sentences were having on prisoners and their families.

"Urgent action is needed. The government should convert these discredited sentences into an equivalent determinate sentence, with a clear release date, and provide full support to people returning to their communities," he said.

"Only then will the damaging legacy of this unjust sentence finally be confined to the history books."

The Ministry of Justice said it recognised there were problems in the system, adding that Justice Secretary Michael Gove had asked the Parole Board to urgently look at how IPP offenders were handled.

Mr Gove said in a recent speech to prison governors that there were "a significant number of IPP prisoners who are still in jail after having served their full tariff who need to be given hope that they can contribute positively to society in the future".

What is an IPP?

It is a minimum sentence and the prisoner must demonstrate to a parole board that they are no longer a risk to the public before they can be released

Introduced by the Labour government in 2005, it was designed for serious violent and sexual offenders

Ministers thought it would affect 900 offenders in total but it was applied far more widely, and at its peak there were 6,000 IPP prisoners

The sentence was abolished in 2012 by then Justice Secretary Ken Clarke

He said that it was impossible for prisoners to prove that they were no longer a risk, calling IPPs a "stain" on the criminal justice system

- Published30 May 2016

- Published30 May 2016

- Published18 March 2016

- Published13 March 2014