The intelligence questions for Chilcot

- Published

Sir John Chilcot, chairman of the Iraq inquiry, delivers his findings on Wednesday

In September 2002 President Saddam Hussein summoned his Revolutionary Command Council in Baghdad. He looked "stiff" and "under pressure" as he demanded answers from those round the table. He had just read a new dossier published in the name of Britain's Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) in London.

It contained detailed information about his own regime's capabilities. There was even a claim that weapons of mass destruction could be fired in 45 minutes. This puzzled him, according to accounts gathered later, including from Saddam himself.

Was there anyone in the room who was aware of any capabilities that the president himself did not know about? By turn, each member of the Revolutionary Command Council hurriedly said no, they did not. So what explained the judgement of British intelligence?

Answering that question is one of the central planks of the Chilcot Inquiry due to report on Wednesday. There was an intelligence failure. The extent and who was to blame has proved controversial and the inquiry may give us the most conclusive answers yet.

The issue can be divided into three areas: the reliance by those collecting intelligence on sources who were wrong, a failure of analysis in not challenging the assumption that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and finally, failings in the way intelligence was presented to the public, not least in the dossier that left Saddam himself confused.

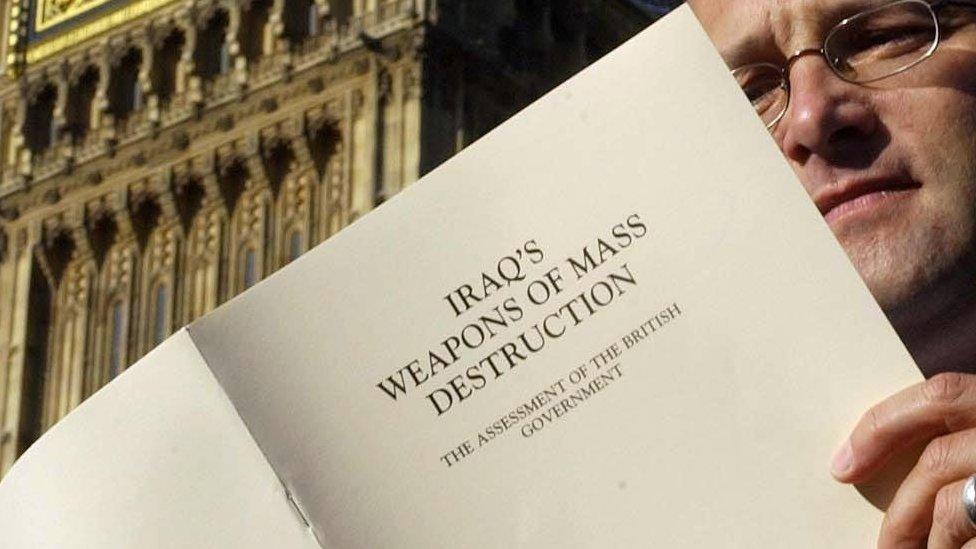

The UK government's 2002 dossier on Iraq's alleged WMD programme was hugely controversial

Graham Greene's novel Our Man in Havana remains perhaps the funniest - but also the most perceptive - critique of the intelligence world.

A vacuum-cleaner salesman manages to pass off designs of the latest model "the atomic pile" as a weapon of mass destruction hidden in the hills, thanks to MI6 officers being a little too keen to provide the goods. The technical experts who might challenge the veracity of the intelligence were never shown the details.

That is pretty much what happened after the hunt for sources on Iraq's WMD picked up pace in 2002. Agents in the field knew what was wanted and delivered but it was never properly checked nor always shown to technical experts in the Defence Intelligence Staff (when one document allegedly showing Iraq purchasing uranium from Niger was seen by international experts they dismissed it as a fake within a day).

There was none of the supporting evidence you would expect to see around a claim like 45 minutes such as where the weapons were stored and manufactured or what the time frame even referred to. That was true of much of the intelligence.

"There didn't seem to be any intellectual rigour in reviewing the information. One can only assume that was because there was a desire for the information to be correct," argues Garth Whitty, who had been a chemical weapons inspector in Iraq in the 1990s.

After the war, MI6 went looking for its sources. A "new source" - much heralded at the time - denied ever having said anything about accelerated production of chemical and biological weapons. The military officer who supposedly had talked about 45 minutes also denied any knowledge.

Hans Blix, the UN's former chief weapons inspector, gave evidence to the Chilcot Inquiry

When they found the intermediary who passed on that officer's report, there was a lot of umming and aahing, one official told me a few years later.

Regarding the sources, Sir Richard Dearlove, the then chief of the UK's Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, may be in the firing line from Chilcot. His critics argued he got too close to power and was too eager to please Downing Street. This is something he has vehemently denied.

There was, though, disquiet among some officers in MI6. Two of them asked to be moved (and some even found a refuge over at MI5).

With the dossier out, inspections began in Iraq. But when the United Nations inspectors visited sites whose locations had been passed onto them by British and American intelligence they found nothing. Secret production facilities hidden in chicken farms turned out to be just chicken farms.

Some 700 inspections took place at 500 different sites and found nothing, including at locations suggested by British and American intelligence. "We assumed that they gave us the best sites they had but in none of those cases did we find weapons of mass destruction," Hans Blix, who ran the inspections, told me as he reflected on events.

MI6 changed the way it checked its sources following the 2004 Butler review

This spoke to a second intelligence failure: one of analysis. A stubborn belief that Iraq had WMD had persisted from the 1990s across the intelligence community and there was an unwillingness to reassess this assumption even as inspectors drew a blank.

What was Saddam up to? In the 1990s he had destroyed his programmes and thought that when inspectors found nothing, sanctions would be lifted. But his fatal mistake was destroying the programmes secretly, most likely to avoid appearing weak at home and to neighbours like Iran.

What that meant was that when inspectors pointed to past known stocks of chemical weapons, for instance, the Iraqis were unable to prove they had destroyed, rather than just hidden, what became known as "unaccounted for materials".

Just days before the war began, the Iraqis were still desperately trying to find new ways to verify that they had poured chemicals into the ground, rather than hidden them.

Sir John Scarlett chaired the Joint Intelligence Committee at the time of the publication of the 2002 dossier

For critics, the failure to reassess assumptions about Iraq was because the train to war had already left the station. They argue the intelligence was ultimately a pretext, a public justification and a tool for persuading the public to support a cause that had already been decided upon: - that cause was regime change.

The final crucial area Chilcot is likely to examine is the presentation of the intelligence to the public. Secret intelligence assessments in March 2002 described the intelligence on Iraq's weapons as "sporadic and patchy" and yet the foreword to the famous dossier that September had the then prime minister, Tony Blair, claiming it was "beyond doubt", external and leaning heavily on the experts of the JIC and their credibility.

Part of this hardening was down to the ability of MI6 to find "new sources" in the summer of 2002, just as the dossier was being drawn up. But blame may also fall on a process which allowed the caveats and qualifications to be lost and the intelligence to be portrayed as stronger than it really was. Any criticism here may fall on the JIC and its then chair Sir John Scarlett.

Much of the detail on intelligence has been raked over already, most significantly in the Butler Inquiry, external (which led to reforms in the way MI6 checked its sources).

But beyond the already well-told story of the weapons of mass destruction, there may be other questions for the spies: did they do enough to predict what might happen in Iraq after the fall of Saddam or provide enough information to military policymakers and the military on the insurgency that then emerged?

Whatever the final verdict, the experience of Iraq is one that casts a long shadow over Britain's spies.

- Published13 August 2015

- Published21 January 2015

- Published29 January 2015

- Published3 June 2016