The Iraq War's hard lessons

- Published

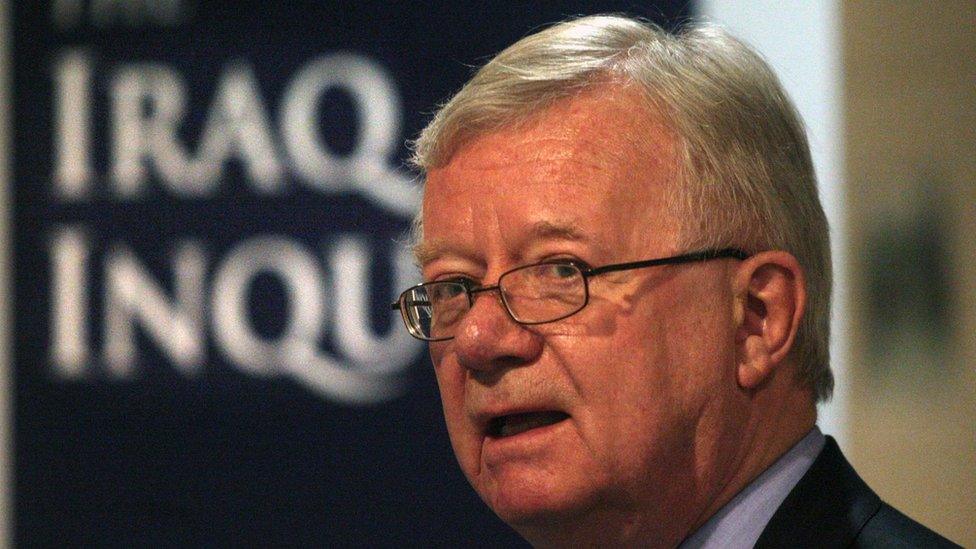

Sir John Chilcot's long overdue, and extremely lengthy report, has the unenviable task of drawing a line under the deeply unpopular Iraq War.

It was a war in which the UK mission in Basra came "close to failure" and which left Britain's military reputation and confidence "damaged". Those are the words of retired Brigadier Ben Barry (Retd) who carried out the British army's own internal report on the lessons learnt.

The families of the 179 British soldiers who died in Iraq are hoping this report gives them the answers as to what went wrong.

Twenty-seven of those servicemen died while travelling in lightly armoured Snatch Land Rovers, a vehicle totally unsuitable to protect them from the threats of roadside bombs and that were dubbed "mobile coffins".

The Snatch Land Rover is just one illustration that Britain's military chiefs were ill-prepared for the fight. Soldiers not only had to rely on poorly protected vehicles but the secrecy surrounding the invasion meant that some kit, including extra body armour, couldn't be sent until the last minute.

The attack on Royal Military Police at Majar-al-Kabir in 2003, which left six Red Caps dead, was a wake-up call to the nation that this was not going to be an easy fight.

Not only were they surprised by the levels of resistance and largely unaware of Iraq's sectarian divide, they didn't even have satellite communications to call for help and reinforcements.

The BBC has spoken to a number of senior officers involved in the preparation for the war, the invasion itself and the subsequent occupation - including those who gave evidence to the Chilcot Inquiry. Many are expecting strong criticism of the military and for the Army in particular.

It's a chapter that has left deep scars. One senior officer described it as an "embarrassment", another said that it left them "humiliated" in the eyes of their American allies. Their hope is that, whatever the criticisms, it won't detract from individual acts of bravery shown by soldiers on the ground.

But it's clear - even before the publication of Sir John Chilcot's report - that military chiefs were ill-prepared for what happened after the success of the initial invasion.

The Chilcot report will examine UK involvement in Iraq from 2001 to 2009

Most of the failings go back to the lack of planning. Beyond the immediate invasion British forces had no clear orders. Major General Tim Cross (Retd), who was one of the few trying to prepare for the aftermath of the invasion, said he'd warned Tony Blair that they should not begin the military campaign without a more coherent post-war plan.

While he said it was easy to blame the Americans, who were in the driving seat: "The UK should have done far more to get our minds round this issue."

There was a mistaken hubris, a belief that it would turn out all right. To some extent the British military had been seduced by recent successes: from Northern Ireland, the Falklands and the first Gulf War to more recent small-scale interventions in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. Top brass wrongly assumed they were well prepared for Iraq.

The Army hoped, and even believed, that it would be the same in 2003. There was an assumption that they would be greeted as liberators, rather than infidel invaders - as shown by the removal of hard hats for soft berets in the early stages of occupation.

There was no real understanding, either, of the malign influence of Iran and the Shia militia, or what would fill the void once the apparatus of the old Iraqi state had been dismantled, on American orders.

The British army's ingrained "can-do" spirit can help in overcoming obstacles, but it might have also hampered its ability to highlight problems and to speak "truth to power".

The Army may even have believed in boasts that Britain "punched above its weight". The initial British invasion force of 46,000 troops was soon reduced to a third of that number, leaving UK forces thinly stretched across an area the size of England.

This led to another problem. While getting bogged down in Iraq the Army was already turning its attention to Helmand in Afghanistan. Some senior officers have argued it was already ill-prepared for one significant long-term deployment, let alone two.

Sir John Chilcot has every reason to ask why the Army was arguing to escalate its military intervention in Afghanistan while it was still struggling to make a difference in Iraq.

Questions have been asked about the escalation in British involvement in Afghanistan while the Iraq conflict was continuing

Lt General Sir Robert Fry (Retd), who was charged with scaling-up the British intervention in Helmand, says, in reality, the British were looking for an exit once it became clear that there were no weapons of mass destruction and it became harder to maintain public support for the war.

Just as the remaining British forces withdrew to Basra airbase, the US was doing the opposite and expanding its mission to defeat the insurgency. Ben Barry concludes "there is good evidence that US forces in Iraq changed and adapted faster than the British".

While the British became increasingly worried about casualties and the public perception of the war, US President George W Bush took the decision to create a surge in US forces. Unlike the British, the Americans also embedded their troops with Iraqi forces and introduced new mine-protected vehicles - the MWRAP.

One of the architects of the Iraq War, the former US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, once famously said: "You go to war with the army you have." But his successor, Robert Gates, added: "But you damn-well should move as fast as possible to get the army you need."

The families of those who served, often with bravery, in Iraq and the families who lost loved ones, have every reason to ask why Britain did not learn that lesson.