Dreams and desperation in the Calais camp

- Published

Aid workers are renewing their calls for the government to speed up the process of resettling child refugees in Britain, following the death in Calais of a 14-year-old Afghan boy, who was run over as he tried to get into a lorry heading to Dover.

Some eyewitnesses say the lorry driver spotted him and started swerving to force him off and there are reports that the vehicle which ran into him when he hit the ground, did not stop to help.

According to the aid organisation Help Refugees, the boy had an older brother living in the UK, giving him the legal right to come to this country, but he was so frustrated with the slow application process that he decided to risk jumping on a lorry instead.

One of his Afghan friends described him as "a kind boy with a good mind, who was trying to learn English in the camp and hoping to go back to school when he reached the UK".

So far this year, 12 people are reported to have been killed including several children - most of them while trying to get on board lorries near Calais port.

And almost all have come from the refugee and migrant camp in Calais known as the Jungle, where latest estimates say at least 9,000 people are now living - the majority from Afghanistan, Eritrea and Sudan.

So many have arrived since the authorities bulldozed half of the camp earlier this year, that aid workers are finding it increasingly difficult to find space for newcomers to pitch tents on the mud and sand.

An estimated 9,000 refugees live in the camp known as the Jungle

Providing sufficient food for the burgeoning population is also a problem.

Amidst the squalid, tightly packed tents and makeshift shelters, the atmosphere is becoming increasingly febrile for other reasons too, particularly the fear that the French authorities will go ahead with their stated aim of closing the camp within the next few months.

One local official hinted recently to community representatives that the process could begin within weeks, although a spokesman for the regional authority has denied this.

Estimates of the number of unaccompanied children in the camp vary from 800 to more than 1,000 and so far very few have been granted the right to come to Britain through legal means.

And this despite an amendment to the Immigration Act coming into force earlier this year, committing the government to take in some of the thousands of unaccompanied refugee and migrant children now in Europe.

Among those waiting in the camp, still hoping he will eventually be allowed to set foot in the UK legally, is Tito, a 17-year-old boy from South Sudan.

Richard Galpin meets Tito, living in the Calais camp

Initially, as we walk together through the camp to his tent, he seems upbeat - laughing and smiling as he greets friends along the way.

But as we sit down for the interview, his mood darkens abruptly and disturbingly.

The pain of recalling why he left his family and home, and what he went through to get to France, showing on his face and in his voice.

"I lost my Daddy in the war (in South Sudan) two years ago," he says.

"It is very hard if you lose your father, you cannot complete your life… and every day I was losing someone from my family."

But his search for peace and security was still a long way off as he travelled north to take a boat from Libya to Europe.

The packed boat capsized and sank, leaving hundreds dead, including his friends.

As a strong swimmer, Tito was among those who survived and was even able to give his lifejacket to a 12-year-old boy who was screaming for help.

But after all this, his dream of reaching Britain remains as far away as ever.

He has no idea if or when his application to be resettled in the UK will be accepted and time is running short because in a few months he will have his 18th birthday, making him too old to be eligible.

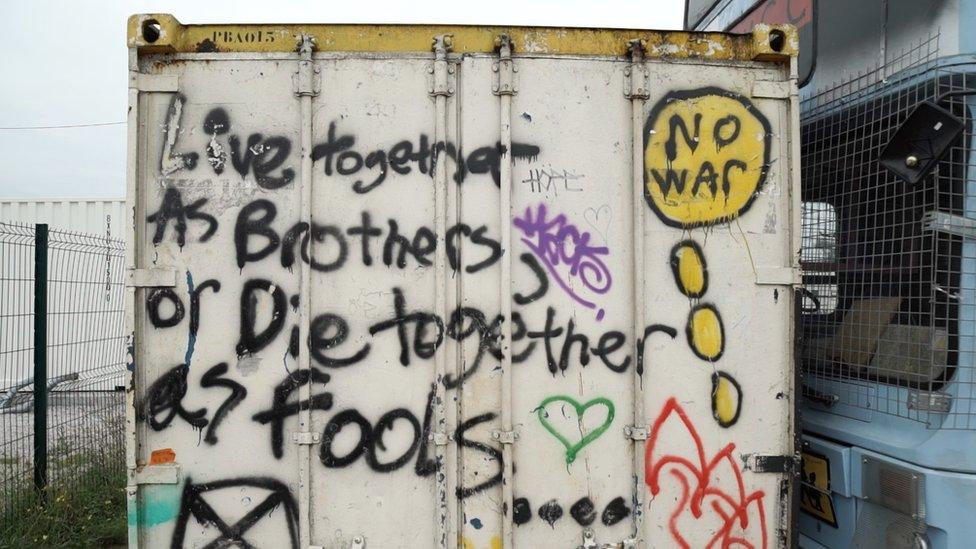

There is uncertainty about the future of the camp

Also looming on the horizon is the prospect of the camp being pulled down by the authorities, which would destroy the sense of security he has managed to create here.

"We have more friends here, it's like my family, my brothers, I don't feel alone," he says.

A Home Office spokesman told the BBC they were working as fast as possible on the child refugee issue and so far this year more than 120 have been given the green light to come to Britain.

He stressed that the ministry has to follow a process involving EU and French law and has to ensure there are places in Britain available for the children.

But aid workers are warning that the longer the wait, the greater the chances that more children will risk their lives trying to jump into lorries near Calais port.

And that means more could die.

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 September 2016

- Published7 September 2016

- Published30 August 2016